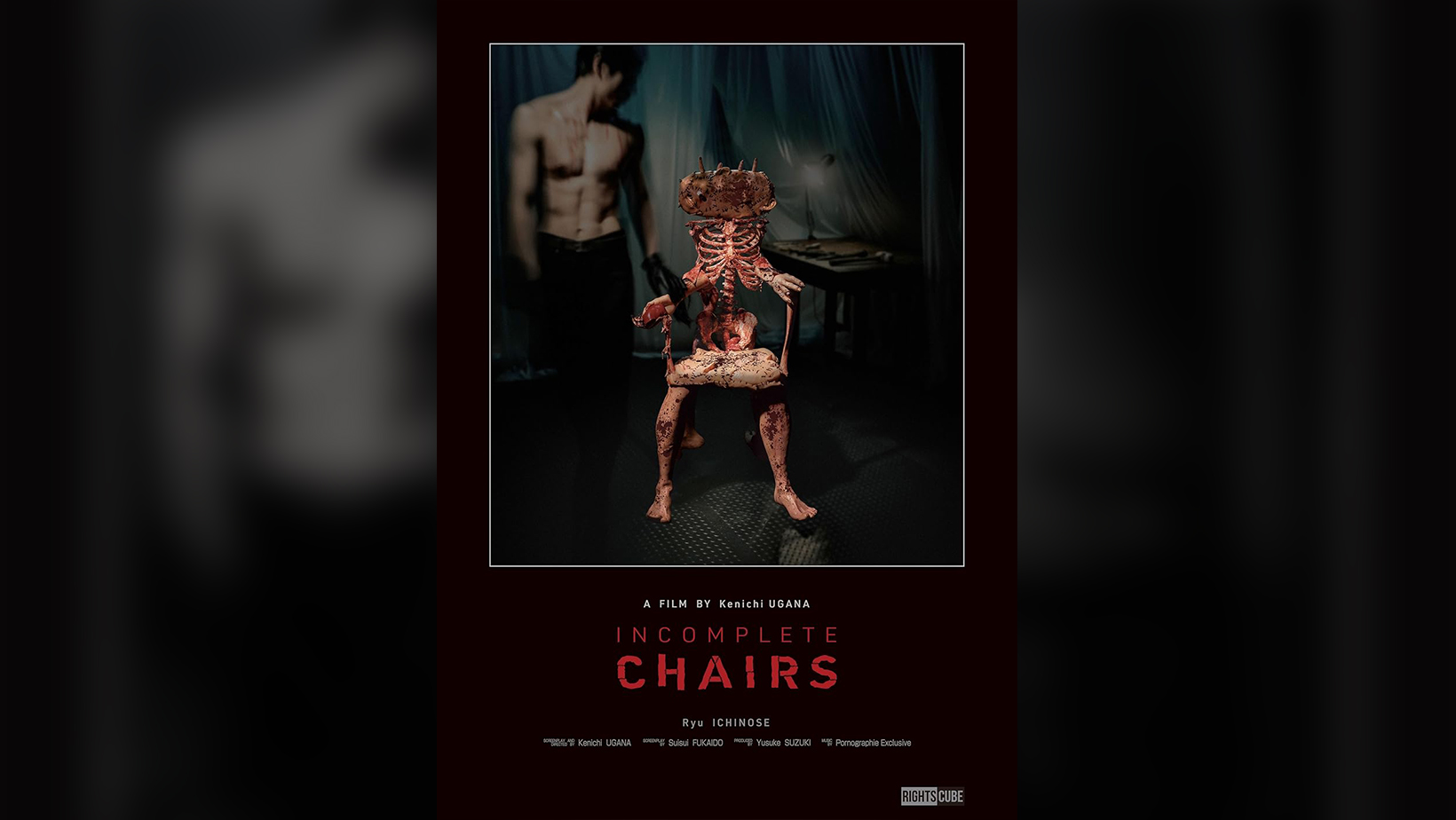

Director Kenichi Ugana is profoundly interested in exploring societal outcasts and obsessives in his work, whilst maintaining a distinct punk and transgressive style. With titles such as Visitors: Complete Edition (2023), Extraneous Matter: Complete Edition (2021), and The Curse (2025), to name a few, the young director’s vast number of films feature elements from all different genres—not fitting into any single one. His latest film, Incomplete Chairs, adds to his unique filmography with a surreal, nihilistic atmosphere permeating every splatter-filled frame. The horror-satire follows Shinsuke Kujo, an inscrutable master craftsman, as he lures people to his apartment under the false pretence of hiring them to be his assistant in his pursuit to create the perfect chair. Ryu Ichinose seems to channel Patrick Bateman in his cold, callous and calculating performance of Kujo, with his clinical monologues revealing his contempt for modern Japan’s hollow consumer culture and its self-destructive imitation of Western ideals.

Throughout the film, Kujo is obsessed with his creation of the chair, mirroring the artistic struggle and frustration of being trapped in an incessant pursuit of perfection. The title, Incomplete Chairs hints towards the idea that this pursuit is never-ending and ultimately futile in its chase of apotheotic status. Kujo’s monologues often hint towards criticism of the hollow nature of Capitalism, with chairs standing in as status symbols and representing the high-brow art culture creating restrictive elitism and class immobility.

The examination of class and wealth is encapsulated in Kujo’s repetitive interview technique. Amidst his small, suffocating apartment, Kujo conducts every interview with the question: “If there is a ten-thousand yen chair and a one-million yen chair, which one would you sit on?” However, no matter the answer he receives from his candidates, Kujo is unsatisfied and brutally murders each person he comes into contact with. The interviews and chairs are merely a “means to an end” to enact his ruthless punishment on the world, perhaps highlighting the erosion of humanity under a Capitalist society. Each victim is dehumanised: we never learn their names, backstories or understand why Kujo has selected (or stumbled upon) them as victims. In literally using their maimed and dismembered bodies to create his ideal chair, their dehumanisation is outlined, and so too is the idea that they are commodities themselves. In stripping the victims of their humanity, the viewer is left to focus not on the who, but rather the why of Kujo’s intentions.

Kujo’s clinical approach to his interviews and killing is reflected in the cool-toned colour palette. The film is awash with cold, unfeeling blue hues, and his apartment radiates stark whites, which represent his self-assertion that, somehow, he has been ordained by God to enact divine punishment. The name Kujō (九条) in Japan evokes aristocratic bloodlines of imperial Japan’s regent houses, while kujo (駆除) means “extermination” – this is particularly symbolic as the character embodies both elite refinement and violent purging. Despite the colour palette being cold, the scenes of violence are visceral and gory, shocking the audience and juxtaposing the detached process of murder. This incongruous tone represents the contradiction between his cold methodology and brutal results, mirroring his psychology: he feels as though he is superior and has made it his life’s mission to eradicate and purge those below him with acts of great violence.

To further compound this, the setting of the apartment’s tight interior, plastic-wrapped and dripping with innards, symbolises the antagonist’s hidden, nihilistic and macabre desires to rid the world of “idiots”. As the film progresses, the setting bleeds out into the wider world, with Kujo meeting Natsuko Kato, an art buyer, whose professional fascination with his work makes her the only character able to penetrate his inner world. Kujo’s work has been making an impact on the online art sphere, which spurs Kato to interview him. However, her connection to him reveals the film’s central irony: that his artistry is a hoax, and his chairs are imitation designs. Kujo isn’t a master craftsman, but a con artist. This revelation outlines Ugana’s commentary on the facade of social media having the ability to fabricate credibility where appearances overshadow authenticity.

The spatial metaphor comes full circle by the end of the film as the shot of Kujo prowling the streets of Japan shows that despite his artistic efforts to fulfil his own needs, his journey is incomplete, and so too is his destruction. Kujo has left his apartment, which acts as both his sanctuary and his prison, to venture out into the wider world, showing that his violence, like his chairs, will always be incomplete.

Incomplete Chairs is by no means an incomplete film as it deftly weaves confronting gore with dark humour to explore Japan’s relationship with consumerism and the ability of social media to create inauthentic social status symbols. The visual communication with the colour palette, along with lighting and shadow, used to heighten the dismemberment and Ryu Ichinose’s compelling performance as the menacing and mysterious craftsman, creates an unsettling and memorable film. Kenichi Ugana has hinted at a sequel, ‘Incomplete Tables’, making the whole domestic scene complete and fans ready to set the table and eat it up – blood and all.

We watched Incomplete Chairs (2025) at this year’s Grimmfest 2025

More Film Festival Coverage

Medium-Sized Horror Bites From BITS 2023 We are thrilled to be reviewing features and shorts for the Blood In The Snow film festival again this year, and offer here our… Six days of unforgettable cinema experiences are over. In its 25th anniversary edition, the Japanese film festival Nippon Connection once again set an audience record with around 20,000 visitors over… Fabián Forte’s Legions, an Argentine horror-comedy that premiered at the 2022 edition of the Fantaspoa Film Festival, is a delightful concoction bound to please fans of Sam Raimi, Alex de la… Imagine waking up one day to a bedroom unfamiliar to you, with a stranger lying on the bed beside you. Sounds like a normal Saturday morning? Well, what if that… In the tradition of pseudo-local-TV broadcasts like Ghostwatch and WNUF Halloween Special, homegrown horror heads to N.Ireland in Dominic O’Neill’s Haunted Ulster Live. Set in 1998, TV newscaster Gerry Burns… Showing as part of the 2021 FrightFest lineup, King Knight marks the fifth feature length film of Richard Bates Jr. Reuniting with fan favorite actor Matthew Gray Gubler, who appeared…Mournful Mediums Short Film Reviews [Blood In The Snow Festival 2023]

Nippon Connection 2025 Award Winners

Legions (2022) Movie Review – Aging Shaman vs. Self Help

Affection (2025) Film Review – Amnesia Horror with a Sci-fi Twist [Brooklyn Horror Film Festival 2025]

Haunted Ulster Live (2023) Film Review – Tune In for Horrors Near You [Unnamed Footage Festival 7]

King Knight (2021) Film Review – A Coven Comes Undone

![Mournful Mediums Short Film Reviews [Blood In The Snow Festival 2023]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Mournful-Mediums-cover-365x180.jpg)

![Affection (2025) Film Review – Amnesia Horror with a Sci-fi Twist [Brooklyn Horror Film Festival 2025]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Untitled-design-8-365x180.jpg)

![Haunted Ulster Live (2023) Film Review – Tune In for Horrors Near You [Unnamed Footage Festival 7]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Haunted-Ulster-Live-Title-Card-365x180.jpg)