Did you know Hideaki Anno, best known for Evangelion, has also tackled themes of inner turmoil and depression in live action?

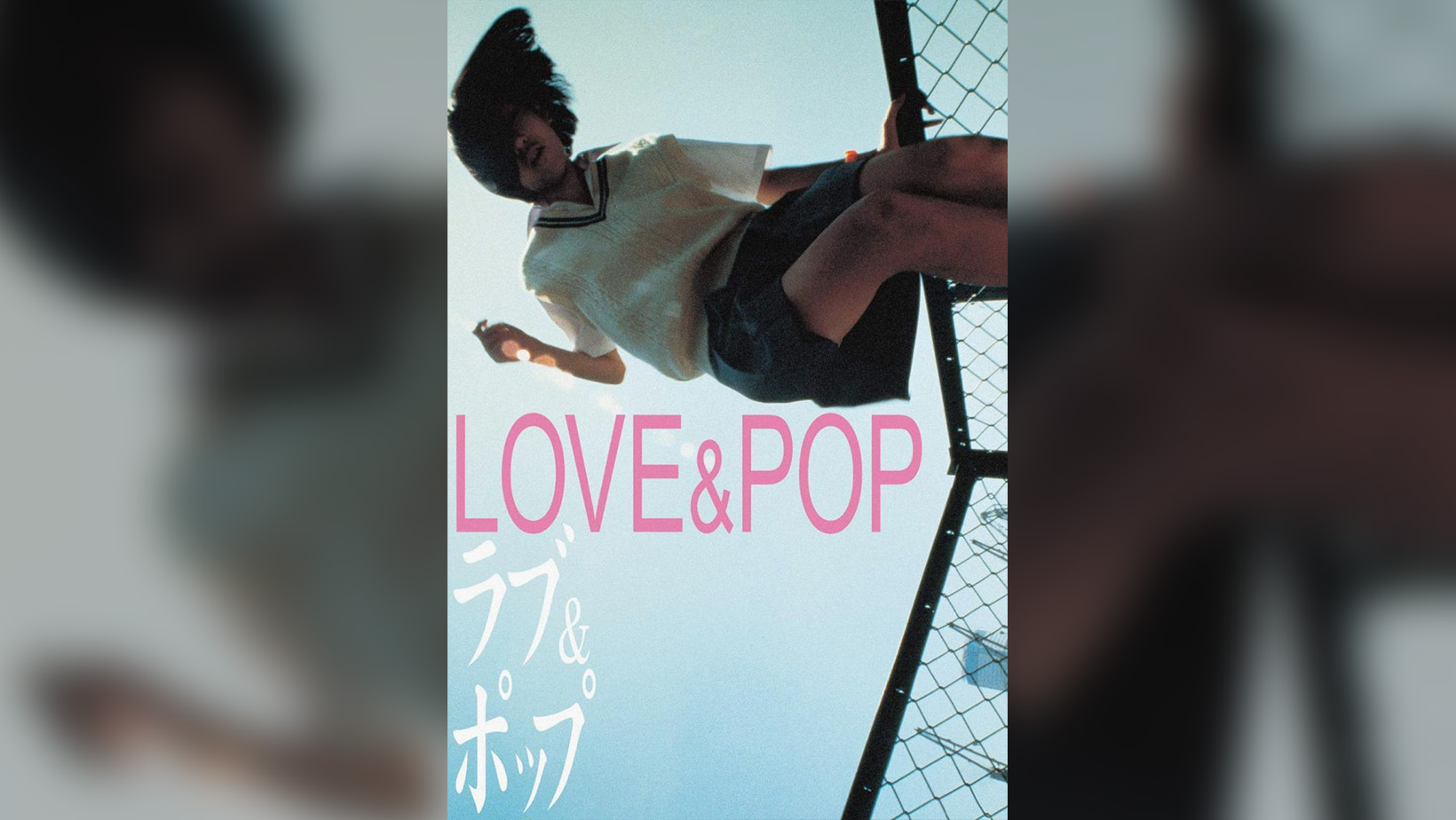

If you don’t, no one can blame you. It’s easy to associate Anno with mechas, apocalyptic imagery, and psychological breakdowns. But in his 1998 live-action debut Love & Pop, he trades in the esoteric horrors and robots for something just as disquieting—real life.

Based on Ryū Murakami’s 1996 novel, Love & Pop follows Hiromi Yoshii (expertly played by Asumi Miwa), a Tokyo high school girl who becomes involved in the world of compensated dating (enjo kōsai)—a practice where older men offer money or lavish gifts to young women in exchange for anything from casual conversation to more intimate favors.

But why does Hiromi do it? That’s part of the film’s ambiguity. She isn’t struggling at school, nor is she from a broken home. She lives with a loving—if somewhat oblivious—middle-class family and spends most of her time with her three close friends: Sachi, Chi, and Nao. None of them are in financial trouble. They try enjo kōsai mostly for the thrill, the occasional expensive dinner, and a bit of extra cash. Despite what the media of the time suggested, they’re not delinquents—they have hobbies, ambitions, and dreams for the future.

And yet, the film’s tension begins with Hiromi’s growing sense of emptiness. She feels like the least remarkable of the group—not as talented as Sachi, not as mature as Chi, not as charismatic as Nao. When she tries on a topaz ring during a shopping trip to Shibuya, she feels, for a brief moment, like someone else—someone special. That fleeting feeling becomes a fixation, and when she learns the ring is only on sale until 9 p.m., she becomes desperate to buy it.

With time running out, Hiromi dives headfirst into enjo kōsai, using a cellphone lent to her by a mysterious gay man Nao met earlier in the day. From there, she begins calling strangers—men willing to pay for her time—and finds herself drawn into increasingly degrading, and at times dangerous, encounters. Love & Pop doesn’t sensationalize her choices; it simply observes, with a mix of empathy and detachment, as a teenage girl tries to locate her sense of worth in a society all too ready to put a price on it.

Love & Pop not only tackles a deeply rooted societal issue in Japan—it does so without ever feeling patronizing or moralizing. Instead of preaching, it immerses us in Hiromi’s perspective, allowing discomfort and ambiguity to speak for themselves. At the same time, it’s a technical marvel. Hideaki Anno brings the same experimental spirit he’s known for in animation into live action, using a variety of digital cameras—some handheld, others placed in unconventional spots like beneath skirts—along with rapid scene cuts, split screens, and erratic framing to mirror Hiromi’s emotional state. The result is a film that feels intimate, restless, and disorienting—but also, at times, strangely voyeuristic.

It’s as if Anno is opening a window into the most intimate corners of Hiromi’s mind—while simultaneously making us feel just as intrusive as the men who pay for her time. We might not be offering money, but still—what gives us the right to watch every detail of her life so closely? Anno clearly wants us to feel uncomfortable, and it works. The film’s experimental camera work and unsettling themes may deter some viewers simply because they can’t handle the discomfort. But if you’re willing to stay with it, Love & Pop reveals itself as something rare: a tender, aching portrait of what it means to be a teenage girl in a world that refuses to truly see her—so much so that she begins to forget her own worth.

That’s what makes Love & Pop so striking. There’s a lot of valid criticism about how male directors often fail to portray real, complex female characters. But that’s not the issue here—because Anno doesn’t try to explain Hiromi. He wants us to listen to her. His camera might feel invasive, but his gaze isn’t cruel. Like with Shinji in Evangelion, he’s less concerned with providing answers than with capturing emotional honesty. It doesn’t matter whether you’re a boy in a plug suit or a girl chasing meaning through a topaz ring—being young and lost is terrifying, sometimes even dangerous. And Love & Pop refuses to look away from that.

We watched Love & Pop (1998) at this year’s Nippon Connection.

More Film Festival Coverage

Showing as part of the 2021 FrightFest lineup, King Knight marks the fifth feature length film of Richard Bates Jr. Reuniting with fan favorite actor Matthew Gray Gubler, who appeared… The Unsolved Love Hotel Murder Case Incident is a 2024 Japanese found-footage horror film written and directed by Guy and Dave Jackson. An Osaka-based, English-born director, the mononymous Guy is… The Glenarma Tapes is a 2023 Northern Irish found footage horror film, written and directed by Tony Devlin with additional writing from Paul Kennedy. Although the film presents itself as… Struggling to quit smoking, Piotrek’s fiancée signs him up for a course at an institute focused on providing help for men. However, after a room mix-up, he finds himself in… BITS and Bytes is a collection of short horror films screening on the third night at Blood in the Snow Film Festival 2024, including several from series that viewers will… Set during World War II, Kiah Roache-Turner’s Beast of War (2025) follows a battalion of young Australian soldiers as they prepare for their first deployment. Focusing primarily on Leo, played…King Knight (2021) Film Review – A Coven Comes Undone

The Unsolved Love Hotel Murder Case Incident (2024) Film Review – From Drunken Idea into Hungover Reality [Unnamed Footage Festival]

The Glenarma Tapes (2023) Film Review- Into the Woods! [FrightFest]

Alpha Male (2022) Film Review – The Absurd Temple of Bromanity!

Bits and Bytes Short Film Reviews – Blood in the Snow Film Festival 2024

Beast of War (2025) Film Review – Shark or a Bullet? [Fantastic Fest 2025]

Hi everyone! I am Javi from the distant land of Santiago, Chile. I grew up watching horror movies on VHS tapes and cable reruns thanks to my cousins. While they kinda moved on from the genre, I am here writing about it almost daily. When I am not doing that, I enjoy reading, drawing, and collecting cute plushies (you have to balance things out. Right?)

![The Unsolved Love Hotel Murder Case Incident (2024) Film Review – From Drunken Idea into Hungover Reality [Unnamed Footage Festival]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/The-Unsolved-Love-Hotel-Murder-Case-Incident-2024-cover-365x180.jpg)

![The Glenarma Tapes (2023) Film Review- Into the Woods! [FrightFest]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/The-Glenrama-Tapes10-365x180.jpg)

![Beast of War (2025) Film Review – Shark or a Bullet? [Fantastic Fest 2025]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Beast-of-War-cover-365x180.jpg)