There is a good reason why Don’t Look Now so rarely feels like it is a horror film. It is much too concerned with going about its daily business as if nothing terrible actually happened. Opening with a traumatic turn of events that will lead to the image of Donald Sutherland rising from some primordial pool of water with the body of his drowned daughter in his arms, face dripping with an anguished howl, it will only be a brief acknowledgment of the terror that lives at the heart of this film. By the next scene he will be busy at work, seemingly unaffected as if we have skipped over the entirety of the grieving process. The child is simply gone, as if his memories of her have been loaded down with stones and allowed to sink out of view, back to where he found her.

It’s in this twilight of emotion that Don’t Look Now resides. It seems to deeply understand one of the great horrors that comes with living through a traumatic event: that no matter how devastating it is, it will never be enough to stop the next day from coming. The shops on your street will keep opening every morning, and the same faces will still be found at the bus stop waiting to begin their morning commute. If you turn on your television, the local weatherman will somehow still see a future to forecast. Maybe with rain, but also maybe not. And as the night comes, if you look up at any window, you may find the light of other lives still daring to be lived shining down at you. It’s almost as if your pain is entirely irrelevant. At least until you realize that you too have continued going on, and whatever has hurt you, has now gotten behind you. Even if you don’t think it has any right to be back there.

Life will never entirely return to normal though, a lesson Sutherland’s character will slowly learn while trying to distract himself restoring churches in Venice. These memories he has tried to bury are what haunt the film, constantly rising in his conscience like a body rising to the surface of the water that drowned it. His past, no matter how painful, is always nearby, rippling just beneath the life he is trying to busy himself with. And as both Sutherland’s present and future also become tangled into the mix of director Roeg’s elliptical editing style, the world that surrounds him seems to become an echo of that howl of anguish he let loose in the opening moments of the film: growing fainter but returning again and again and again.

Even during moments that release him and his wife from this trauma (particularly in one of the most intimate of any love scene ever filmed by two A list actors willing to maybe actually hump on screen), will be intruded upon by scenes from the near future where they are already dressing and moving on from this tenderness. It’s as if the hope of ever living in the moment has been erased for them. They will forever be lost contemplating the fragmented shards of their inescapable memories and recoiling from their equally inescapable future.

How startling it will be then, that in a film where the past has been treated as an undertow, one cannot swim free from, and the future seems irrevocably fated, that we will be hit with a moment that exists almost breathlessly in the Present. There will be little preparation for absorbing its impact. Or for the audience to fully grasp what they’ve seen. It will just happen to them, and then they will be ushered out into the cold hard light of the lobby, unable to reconcile when the film they were watching suddenly became so frightening. In this way, the horror of Don’t Look Now will be delivered to those who watch it like their own personal trauma. One they can take the time to decipher, or instead bury deep inside of them, only to come face to face with it again sometime in the future of their nightmares.

More Film Reviews

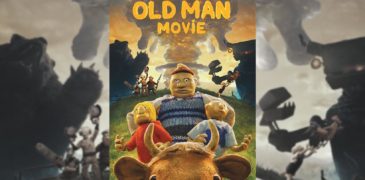

Japan seems to have nailed the absurdist comedy, whether that’s big budget to small indie features, no other country is comparable in wit at embracing the peculiar. Available at Japan… Welcome to Raccoon City is very different in style from the Resident Evil movies featuring Milla Jovovich. While also live-action, it embraces a very different feel and quality, though is… The Old Man: The Movie (Vanamehe film) is a 2019 Estonian stop-motion animation, written and directed by Oskar Lehemaa and Mikk Mägi with additional writing from Peeter Ritso. The film… It’s understandable why Japanese filmmakers focus so often on the feudal era in their horror cinema. It’s a setting so naturally horrific in the plight and pain of the peasant… The smiley face murders exist as a modern urban legend, a way to explain the mysterious drowning deaths of college/university-age men. This comes from a multitude of cases where near… In the dystopian landscape of Cape Town, South Africa, Ryan Kruger’s 2025 sequel to Street Trash (1987) takes viewers on a gore-filled adventure through the perils of class warfare in…I, Dolphin Girl Film Review – Supersonic Head Explosions!

Resident Evil: Welcome to Raccoon City (2021) Review – Itchy, Tasty!

The Old Man: The Movie (2019) Film Review – “Adventures, Robots, Explosions”

Ugetsu (1953) Film Review – Feudal-Era Horror

Smiley Face Killers (2020) Review – College and University Bros Beware!

Street Trash (2024) Film Review – Explosive Social Commentary