Jigoku narrates the tragedy of unatoned wickedness with poetic piquancy, proving that Japan and horror are efficacious accessories that constantly innovate cinema. As expected from the monumental master of Japanese horror, Nobuo Nakagawa‘s seamless combination of surreal imagery and horror: a feat that breathes frenzy and immortality to a classic and timeless arthouse horror.

The story centers around a theology student, Shiro Shimizu, who pursues an escape from crime and guilt after a hit-and-run incident. The crux of the film is the occurrence of mentally jarring arrangements of sounds and images with the bodacious rounds of crude collages of cruelty that makes us uncomfortable. However, the horrific appeal patented on the film is more than its unnerving images and outlandish gore. Although the absence of solid emotional investment and decent scares are quite displeasing, Nobuo Nakagawa still engineered a nightmarish spin with constantly shocking turns that would later manifest a gratifying culmination. His bold direction and imaginative horror flairs paved the way to a paradigm shift in the horror genre.

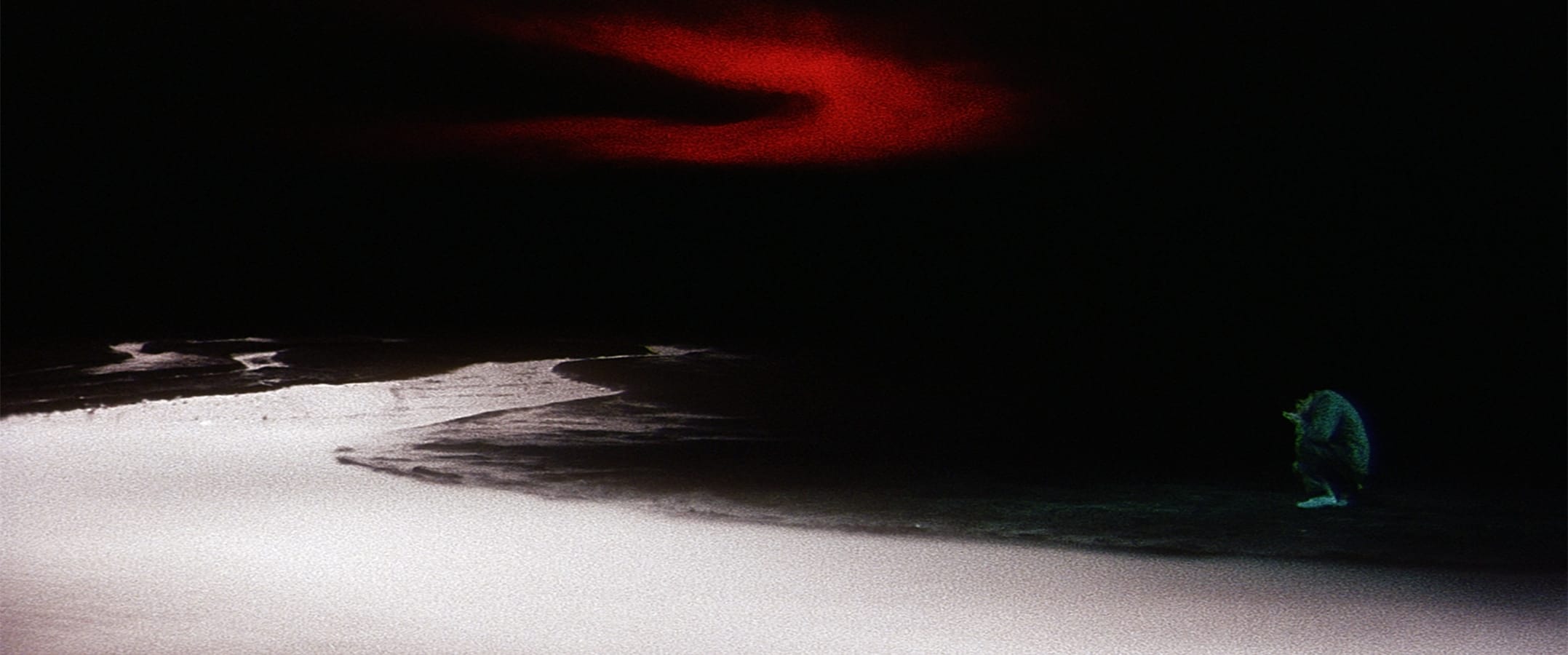

Torture and hell are prevailing mechanisms to exploit cheap and cowering panic. However, the film sequenced hell artistically, where various symbolic tortures, deafening grievances, and chilling folk chants spin diabolical and imaginative awe that evokes how cataclysmic unatoned sins could be. Nakagawa employed more effort in overwhelming the characters with unremitting disturbances that haunt them in the long run. Those who don’t feel any amount of guilt rancorously live the lush life, but those who already tasted the toil and agony of being repressed and held down by guilt frequently sustain episodes of anxiety and confusion. While their vile apathy and unrepentance released them from carrying a burden when they are still living, the consequences of their imprudence become severe when they die. As Shiro’s sins accumulate, so do his unconfronted feelings. The world is already hell, where guilt-ridden people either suffer or find evil consoling.

Guilt is the recurrent theme of the film. This feeling of self-reproach becomes tangible in the form of Tamura. His odd and sudden manifestations aren’t solely appropriated for shock value, but a personified warning that guilt is something that cannot be totally secluded and departed from. Guilt follows Shiro like a shadow. As the pile of bodies heaps up as time goes by, so is the shadow of it that shrouds and swallows him. Hell, for him, is a state of mind, unfaltering turbulence that torments and corrupts his former youthful soul. Like hell, the man is confined in claustrophobia and provocative circumstances that would later contribute to his descent into madness. However, we never see him succumb to this madness, instead, we see him suffer from it in hell.

But hell is more than meets the eye, and the film’s grotesque imageries prove this. The angst bound with the unconfronted guilt is just a presage of the grave consequences of unattended sins awaiting in hell. The people endure various ways of damnation in Nakagawa’s reimagining of hell. The spiritual realm punishes those impertinent enough to neglect to face the weights of their irresponsible behaviors through perpetual anguish and suffocation from having no room to run and escape. The guilt they once tried to run from when they were still alive is now endlessly exhumed everywhere they go inside hell. This is the concurrent notion of the director’s expressionistic depiction of hell, as he translates the place as a dominant and non-conformist torture cell that doesn’t only scorch our exteriors, but also torments the very foundation of humanity, which is the soul.

The ending is something to ponder on. While Lord Enma allows Shiro to save his daughter, the emotionally torn man was not successful in completing the only task that could have redeemed him. But the man didn’t realize that he’s being toyed and trifled by the evil incarnate. In the end, sheer desperation is the only life support of those who are cast away to the netherworld.

While the deemed “Terence Fisher of Japan“ spawned a number of films that reflect his supreme standing on the Japanese horror scene during the 50s and 60s, Jigoku remains his most esteemed work as its imaginative depiction of hell still transcends modern cinephilia.

More Film Reviews:

For years, film festivals have allowed passionate film viewers the ability to enjoy and celebrate the art of film-making from all around the world. In a lot of cases, well-established… Zombie-driven horror seems to be making a fierce comeback to the movie circuit lately. When one thinks about zombies, the words “apocalypse” and “chaos” instantly come to mind. Most well-executed… Fishing doesn’t have the best reputation in fiction. Going off literature and film and Dick Cheney, one gets the impression it’s boring, it’s vaguely cruel, and it mostly serves as… Devils is a 2023 South Korean crime thriller, written and directed by Kim Jae-Hoon in his first feature-length work. The film stars Jang Dong-yoon (Project Wolf Hunting), Jae-ho Jang (The… If ever there was a personification of “It’s not the Destination, it’s the Journey”, it’s Seiji Tanaka’s 2018 Millennial thriller Melancholic. Released recently in dual format by the pioneeringThird Window… Idiot Boy is a 2023 shot-on-video faux documentary written and directed by Luke De Brún, with additional writing from Dan Doyle. Beginning filming in September 2018, the film was created…Thou’lt Look Back No More; Never, Never, Never, Never, Never. (2021) Film Review

Zombitopia (2021) Film Review – Zombies Take Over Malaysia

Sweetie, You Won’t Believe It Movie Review – Fantasia Festival 2021

Devils (2023) Film Review – The Freakiest of Fridays

Film Review: Melancholic (2019) – Seiji Tanaka’s Millennial Thriller

Idiot Boy (2023) Film Review – A Town Called Malice

I am a 4th year Journalism student from the Polytechnic University of the Philipines and an aspiring Filmmaker. I fancy found footage, home invasions, and gore films. Randomly unearthing good films is my third favorite thing in life. The second and first are suspending disbelief and dozing off.