One: The Muted Victim and the Male Surrogate

Accounts of sexual violence are as old as recorded history. The earliest incidences existed side-by-side with the oldest tales of murder; the slaying of Abel by Cain is only a handful of chapters away from the rape of Dinah by Shechem in Genesis. But unlike the physical finality of murder, where there is a clear distinction between the victim and the perpetrator, modern societies still struggle with the social complexities of sexual assault. For millennia, the law focused on the patriarchal “owner” of the female victim rather than the victim herself. For context of how far-reaching this idea of a woman’s bodily autonomy and sexual agency is, in the United States, this “property” status was so deeply entrenched that marital rape was not criminalized in all 50 states until 1993.

Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of this approach is the consistent erasure of the victim’s humanity. The biblical account of Dinah, found in Genesis 34, illustrates this practice. Throughout her violation and its bloody aftermath, Dinah’s voice is never heard. Instead, the narrative shifts focus to her brothers, Simeon and Levi, who treat her assault as theft and therefore a pretext for tribal warfare and plunder. This ancient dynamic, the silencing of the survivor in favor of a male-led revenge fantasy, foreshadows the problematic foundation of the rape-revenge film genre.

The relationship between perpetrator, victim, and societal law has evolved considerably since the ancient world treated women’s chastity as patriarchal property. In this essay, I will examine how these shifts are reflected in the rape-revenge film genre, specifically through the lens of female agency and divine empowerment. The earliest iterations, spanning from the Old Testament and well into the 21st century, view the victim as property and rely on another, typically male, surrogate to seek vengeance. In these stories, the avenger is framed as the primary focus of the tragedy; the narrative centers on their grief and how sorrow is ultimately weaponized into retributive anger.

In the following sections, I will examine how shifting societal perceptions and the struggle for women’s rights birthed a second generation of films. Beginning in the early 1970s, these narratives transformed the victim herself into an avenging actor who engages in vigilante violence to punish her wrongdoers and, potentially, reclaim her agency. Finally, I will discuss a third variation: the supernatural transition. In this model, the victim is transformed—often through death—into a spiritual entity tasked with balancing the scales of justice that human law has left broken.

The trope of the muted victim as a fulcrum for outrage-fueled, masculine violence is remarkably long-lasting. In 1960, Ingmar Bergman explored this in The Virgin Spring, a story of parental rage and revenge that serves as a metaphor for Sweden’s conversion to Christianity. In the film, based on a 13th-century folktale, the family of the raped and murdered Karin discovers that the men they have sheltered are her killers. The spiritual focus of the film centers entirely on Karin’s father, Töre, who struggles to reconcile his brutal vengeance with his Christian faith. Even Karin’s final appearance at the film’s conclusion reinforces her passivity: as Töre lifts her lifeless body, a spring of water miraculously appears, a symbol of God’s grace and forgiveness offered not to the victim, but to Töre for his actions.

Twelve years later, Wes Craven would revisit The Virgin Spring to comment on America’s unconscious embrace of violence in his highly graphic debut film, The Last House on the Left (1972). In this retelling, Seventeen-year-olds Mari and Phyllis are kidnapped, assaulted, and murdered by a group of nihilistic criminals who inadvertently seek shelter with Mari’s parents. While Craven replaces Bergman’s medieval piety with a gritty, post-1960s disillusionment, the structural erasure of the victim remains intact. Once the parents discover the truth, they enact a sadistic revenge using dental tools, knives and a chainsaw, a sequence that shifts the narrative focus entirely onto the parents’ own moral decay. Just as in the story of Dinah and the folktale of Karin, the victims in Last House on the Left remain silent catalysts. Their deaths are the theft that authorizes the parents to abandon civilization and embrace the very savagery they seek to punish.

Craven’s film is a dirty, gritty affair deliberately crafted to reflect the violent upheavals America was enduring at the time: the Vietnam War and its accompanying protests, violent racial unrest, the assassinations of prominent public figures, and the rise of the counterculture, including the Stonewall Riots. In the documentary Celluloid Crime of the Century(2003) , which explores the making and impact of Last House on the Left, Craven explains that he was motivated to make the film as visceral as possible. He sought to shock audiences out of their complacency with unglamorized violence, specifically contrasting his work with the ‘sanitized’ and distant depictions of war common in the media at the time. Yet, even in this pursuit of realism, the victim remains a static object—a corpse that serves as the moral justification for a different kind of American violence: the vigilante justice of the nuclear family.

This linking of supposedly justified male outrage with vigilante violence is troubling for two reasons. First, the acts of revenge are often as horrific as the original crime, raising questions about the transformative power of vengeance to morally cripple the most seemingly upright citizens. Secondly, this focus results in a total disregard for the victim’s well-being. If a survivor is to move past such life-altering trauma, they derive little benefit from a cycle of further bloodshed that leaves their own emotional wounds unattended. While the victims in The Virgin Spring and The Last House on the Left are dead or assumed dead during the vengeance begins, this pattern of hollow retribution persists across the genre. It defines the DNA of films ranging from the visceral Motorpsycho! (1965) and I Saw the Devil (2010) to the gritty urban justice of Death Wish (1974). Even in nuanced iterations like Mad Max (1979), Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (2017), and Promising Young Woman (2020), which we will revisit later, the “justice” sought often functions as a distraction from, rather than a cure for, the original trauma.

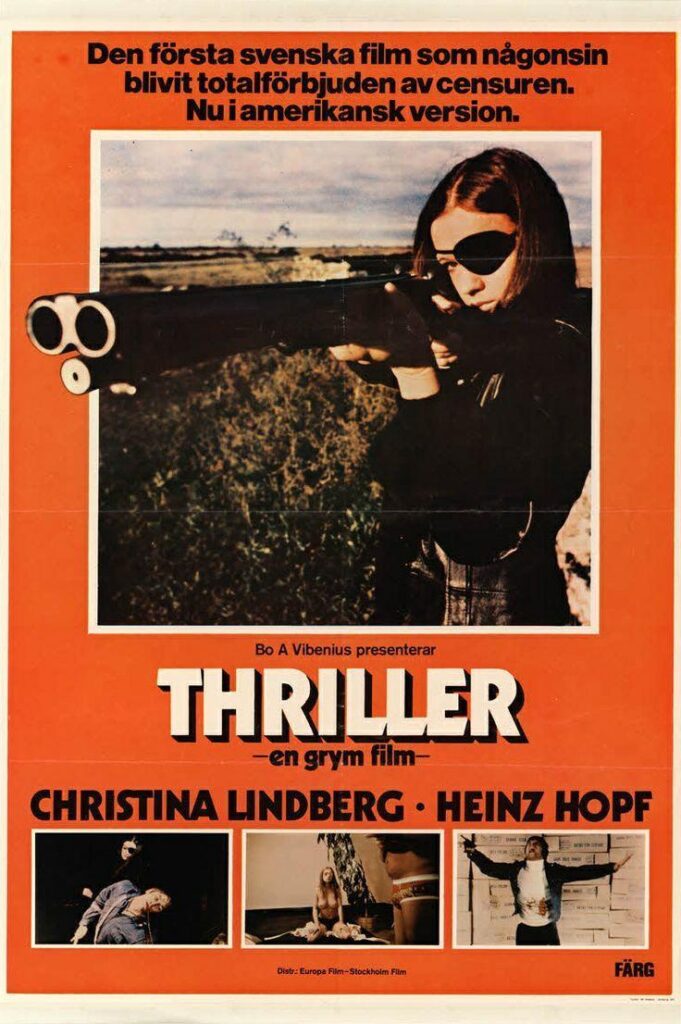

In the next section, we will examine how societal shifts linked to second-wave feminism birthed a new iteration of the rape-revenge genre: one where the victim survives to become her own instrument of vengeance. In the year following the release of The Last House on the Left, the Swedish film Thriller: A Cruel Picture (also known as They Call Her One Eye) provided the template that would lead the genre into new realms. In this era, transformed survivors fought to recapture their personhood, sometimes aided by ‘divine’ or supernatural means that echo the world’s oldest myths. This evolution represents a departure from the male-led surrogate model, placing the burden and the power of justice squarely in the hands of the survivor.

More Film Reviews

Waxwork (1988) Film Review – As it Waxes Nostalgic

Waxwork (1988), Anthony Hickox’s directorial debut, is a half-baked comedy horror film with a tedious build-up, unmemorable characters, confusing lore, and a long-overdue payoff. Although it already fell at the…

An Taibhse (2024) Film Review – I Don’t Think We’re Alone Now

There have been plenty of Irish horror flicks in the past, but John Farrelly’s latest film, Ah Taibhse (The Ghost) marks a first. Marketed as the first and only horror…

Speak No Evil (2022) Review – The Subversion of Bourgeois Expectations

Following an Italian family vacation, Danish trio Bjorn (Morten Burian), Louise (Sidsel Siem Koch), and their young daughter take up an invitation to visit the Netherlands, at the behest of…

Hellraiser (2022) Film Review – A Reconfiguration of Clive Barker’s Harrowing Vision

Hellraiser fans rejoiced when the news broke out that Clive Barker would be regaining the U.S. rights to his novella The Hellbound Heart and the film it spawned in December…

Baby Assassins (2021) Film Review – Moe Moe Kyun!

I didn’t really have a whole lot going during my high school years. I went to class and did stupid hijinks with my friends, but I mostly just watched movies…

The Barn (2021) Short Film Review – Drowning in Raw Chicken

An experimental narrative on loss and ghastly visions that hint at sinister forces, The Barn is a dialogue-free short film with a heavy focus on music. Dense on atmosphere, The…

I am a lifelong lover of horror who delights in the uncanny and occasionally writes about it. My writing has appeared at DIS/MEMBER and in Grim magazine. I am also in charge of programming at WIWLN’s Insomniac Theater, the Internet’s oldest horror movie blog written by me. The best time to reach me is before dawn.