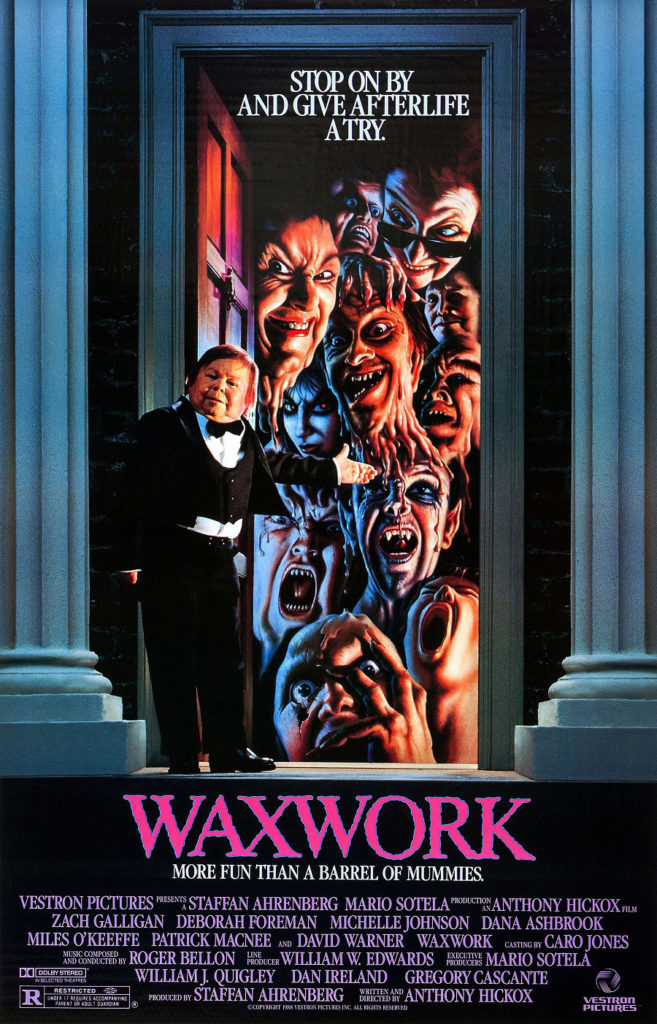

Waxwork (1988), Anthony Hickox’s directorial debut, is a half-baked comedy horror film with a tedious build-up, unmemorable characters, confusing lore, and a long-overdue payoff. Although it already fell at the first hurdle and keeps falling flat, one can find amusement in some elements overshadowed by its poor directorial choices.

The setup of Waxwork (1988) is simple yet a good playground for teenage thrills and horror chills. When a waxwork exhibition opens in town, a strange show master lures teens to a special midnight viewing. During the exhibit, the wax exhibitions transform into time capsules in which the viewer is drawn into the tale of the exhibit. And yet, the film failed to give justice to it. Waxwork struggles to maintain the comedy with its hit-and-miss dialogues. What keeps the humor misfiring is that neither the film nor its characters have a sense of comedic timing. Parody or not, comedy films spare no effort in establishing a farcical rhythm that plays harmoniously with the viewers. For example, the scene where Tony finds himself lost in an alternate dimension and starts ranting with a dry delivery that ends with a sterile takeaway. The actors seem to struggle to deliver the banter in their most humorous way.

The episodes of time displacement lack the flavor that should have worked well since the classic fictional horror and historical monsters are intrinsically iconic figures. From the very first incident to the last, the events aren’t merely coerced to furnish the mystery, but are chosen specifically for the benefit of paying homage. The actors, who obviously have the visuals and potential to effectively perform their characters, turn out lackluster. Shoddy character writing is to be blamed here, as the icons became mere embellishments on the background rather than focal points in every story. In that regard, the character of Marquis de Sade might be the only one memorable for his vivid performance and sufficient exposure. Nevertheless, the amount of shortfall in this area impedes the inaugurated stimulus of the story.

The lore of Waxwork (1988) can also be disorienting and irking. Aside from a failed effort to introduce the wax museum as menacing, it finds itself thrown off balance on whether it wants to portray historical or fictional figures. In one scene, Sir Wilfred mentioned that he and Mark’s grandfather collected trinkets from “18 of the evilest people who ever lived.” Surprisingly, the evilest people consist of both actual and imaginary personages like Marquis de Sade, Count Dracula, the Phantom of the Opera, and Jack the Ripper. The film attempts to cut the fictional ties of some creatures pulled from pop culture and literature and make them real. This kind of inconsistency may not sit well for those who expect a uniform homage to non-fictional freaks. Yet, one can feign ignorance on this misgiving and simply relish the nostalgia brought by showcasing these fictional and non-fictional monsters.

On the other hand, the film is not all bad news. The makeup and effects department is one of its strongest feats. Although the werewolf sequence is quite drab, the werewolf itself is extremely gnarly, which shows how the film strives to triumph on other spheres of interest. Not only the makeup, but the expressiveness of its practical effects play a huge part in this sequence. When the werewolf effortlessly rips a man apart like tearing a single piece of paper, blood and flesh start to emanate from the body. It’s a short-lived scene, but nightmarish for a horror intended to be a comedy.

There is also a particular sequence where it found its smallest redemption. This scene surprisingly hit every element it keeps on missing. It is when vampires chased China while her supposed fiance in that dimension is being dissected for vampire consumption. All death scenes in this sequence are carried out with the right amount of absurdity and creativity that are too ludicrous to not laugh at. The comic timing is on point, especially when the fiance’s lacerated leg is wittingly and unwittingly crippled by the frenzied people in the room. And the bloodshed caused by the tumult is clearly well-executed that fans of gore will feel quenched.

The last act deserves regard as it shatters the dullness of the narrative. It refines the lore of the wax museum by conducting a war that gives the story a more imposing significance than we thought it has. However, what keeps the last act in a bind is that it is unsurprising because neither the wax house maniacs nor the opposition are given the fleshing out they both deserve. Probably the tedious build-up is at fault here, or the demand for a lengthy mythos is a bit too much for the film. But, at least we get the chance to finally witness all the wax figures in action.

Despite the criticisms, the effort of Hickox should be lauded. Aside from seeing familiar icons, we get to relish the majesty of the practical effects of horror films once again. It is a promising attempt in the line of horror films involving wax museums. However, it was a barren outcome. It slips in remaking the 1924 German silent anthology film Waxworks, which focused on historical figures Caliph of Baghdad, Ivan the Terrible, and Jack the Ripper and is stylish and exceptional as a canon to German silent films and horrors about waxworks. Still, Waxworks is a candidate for a cult following.

More Film Reviews

Censor is an innovative psychological horror based in the UK in the 80s, with a story that both discusses and becomes the worst of video nasties – a melding of… As the temperature of sin and plague begins to rise within the town of Loudun, France, it is hard not to notice the white brick walls that fortify the commune… Biotherapy is a Japanese 1986 sci-fi horror that’s aptly described as a slasher merged into a splatter creature feature. The short movie was released as a project from the limited… Techno-horror is a fertile subgenre. Since technology constantly evolves, so must our relationship to it. Our increasingly teach-reliant existence offers countless angles from which to tackle what are, essentially, cautionary… Thorns (2023) is an American sci-fi horror, written and directed by Douglas Schulze. Well-versed behind the camera, Douglas is most known as the writer/director of such films as Hellmaster (1992),… Film trilogies are a tricky business. With the exception of Lord of the Rings and Star Wars, most trilogies don’t set out planning to tell a singular story across three…Censor Film Review (2021) – A Tale of British Video Nasties

The Devils (1971) Film Review – A Study in Villainy and a Comprehensive De-Twirling of a Most Suspicious Moustache

Biotherapy (1986) – An Unknown Japanese Sci-Fi Horror Short

DIGITAL VIDEO EDITING… (2020) Film Review | Learning to Kill Your Darlings (Unnamed Footage Festival 666)

Thorns (2023) Film Review – Natural Thorn Killer [FrightFest]

Fear Street Part Three: 1666 Film Review – Even the Strongest Curse Can be Broken

I am a 4th year Journalism student from the Polytechnic University of the Philipines and an aspiring Filmmaker. I fancy found footage, home invasions, and gore films. Randomly unearthing good films is my third favorite thing in life. The second and first are suspending disbelief and dozing off.

![Thorns (2023) Film Review – Natural Thorn Killer [FrightFest]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Thorns-cover-photo-365x180.jpg)