Part Two: The Rise of the Female Avenger

In the previous article of this series, I discussed how early rape-revenge films reflected the idea that sexual violence was a property crime first, with the family being owed a debt from the perpetrator, and second, that the victim’s fate was less important than the honor of the family. Films like Ingmar Bergman’s Virgin Spring and Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left focused on the fathers’ response to their daughters’ deaths. It is this exact centering of the male ego that second-wave feminism influenced rape-revenge films like Thriller: A Cruel Picture and I Spit on Your Grave sought to dismantle by introducing the avenging actor. In this cycle of films, the survivor would no longer be seen as an “adjacent actor” in her own life; she would become the primary subject and the main character of her own trauma, regardless of her perceived purity.

The cinematic introduction of the avenging actor mirrored a rapid transformation in how American society viewed women’s agency. While sexual violence is a millennia-old issue, the most profound legal and social shifts in the United States have occurred only in the last century. Prior to the 1920s, women were relegated legally and socially to dependence on men and given little autonomous voice. Women’s suffrage, also known as first-wave feminism, delivered the right to vote nationally to women, granting them a formal, legal voice and a whisper of autonomy in the law. What came after, known as second-wave feminism, continued to raise the volume by, among other things, giving women more legal protection against rape and sexual assault.

This clamoring for a louder social and legal voice found a visceral cinematic mirror in Bo Arne Vibenius’ Swedish film Thriller: A Cruel Picture (1973). The protagonist, Madeleine (Christina Lindberg), is literally rendered mute by childhood sexual trauma, a physical manifestation of the historical voicelessness that second-wave feminism was actively challenging. However, just as these new ideals began to reshape narratives of autonomy, the film shifts Madeleine from a passive object of exploitation to a proactive subject. In a radical break from the paternalistic justice of The Virgin Spring and Last House on the Left, she does not wait for the state or a male guardian to rescue her; instead, she systematically builds her own agency, transforming her body into a weapon of lethal resistance.

This reconstruction is born of necessity after Madeleine is kidnapped by Tony, a ruthless pimp who addicts her to heroin and forces her into prostitution. Thriller functions as a dark ode to the ‘stranger-danger’ warnings preached to women and children for generations, ironically ignoring the fact that the majority of assaults are perpetrated by people known and familiar to the victims and survivors. Thriller subverts the outcome of those tales by showing the survivor arming herself. During an intense training montage, Madeleine equips herself with the tools she will use to begin the systematic execution of her captors. This culminates in a ritualistic finale where she buries Tony to his neck and leaves him to be strangled by a horse, effectively reclaiming her narrative from the men who sought to own it.

Vibenius’s film is a flat, joyless experience, further exemplified by Lindberg’s affectless performance as Madeleine. While there is nudity and, in some versions, scenes of hardcore sex were edited in against the director’s will and without Lindberg’s consent, this is not an erotic film. Rather, it is a deliberate inversion of the male gaze that was common in sexploitation films, where the camera and characters perform for the audience’s pleasure. Madeleine’s wordless reactions to her johns and the matter-of-fact way she collects their money mirror the grim stoicism she displays when dispatching her abusers. This lack of distinction is the antithesis of sexual pleasure; the film forces the viewer to confront the transaction of the assault rather than find gratification in it.

In this way, the film forces the viewer to confront the transaction of the assault rather than find gratification in it. In the final act of the film, as Madeleine fights for her freedom, the violence is punctuated by a lazy, almost surreal use of slow-motion photography. As bullets tear through her oppressors, she maintains that same dispassionate, affectless gaze. This is not the high-octane spectacle of a stylized action movie; rather, it is a ritualistic shedding of her oppressors. By stripping the climax of its adrenaline, Vibenius suggests that revenge is not a triumphant cinematic trope, but a mechanical, necessary purging of trauma.

From this point forward, the rape revenge film ceased to be about male aggression and the use of colorful screen violence to restore their besmirched honor. The focus was now on women reclaiming their agency through a grim metamorphosis, taking up the sword against their perpetrators. Madeleine’s journey established the definitive template for the modern heroine: a life interrupted by trauma, a transformative period of physical or spiritual hardening, and a final, inevitable confrontation where the survivor extracts a high price for her stolen personhood.

When talking about the rape-revenge genre, it is impossible to avoid Meir Zarchi’s 1978 I Spit on Your Grave. Upon its initial release, the movie received near universal condemnation for its excessive and graphic violence. Since then, it is still a controversial film as critics and scholars debate the extreme response of the avenging actor, Jennifer (Camille Keaton) to her own attack. Is she a symbolic figurehead of a strong woman freeing herself from oppression or only another male fantasy creation expelling gritty, unglamorized violence for the edification of male viewers? Even today, in an era where audiences are increasingly desensitized to cinematic violence, the film remains a grueling, difficult experience.

This grueling experience is largely due to the film’s pacing; Jennifer’s assault consumes nearly a third of the runtime as she is captured, recaptured and repeatedly violated, then left for dead by a quartet of attackers, led by misogynistic Johnny. While the story and Jennifer’s arc are similar to Madeleine’s, I Spit on Your Grave features a crucial difference from Thriller: In Zarchi’s movie the perpetrators are given screen time to voice their motivations and rationalizations for their crime. Their language is the antithesis of the changing social landscape regarding sexual assault, rooted in an era where a victim’s dress or demeanor, as interpreted by the male observer, was used to manufacture ‘implied consent.

Their casual encounters, Jennifer buying groceries or refuelling her car, provide the meager raw material the men need to weave lurid fantasies. As a city-dweller in a rural setting, she is viewed as an unknown outsider: a blank canvas upon which they paint their predatory delusions. Emboldened by these projections, they eventually strike. Their dialogue, both during the assault and when Jennifer later confronts them, reflects the pervasive phenomenon of ‘rape culture’—a framework where sexual violence is normalized by shifting blame onto the survivor under the pretense that men are slaves to an uncontrollable nature. Ultimately, the film clarifies that the act is never about attraction; it is a grotesque display of power and control, fueled by masculine insecurities regarding the independent woman.

After surviving her ordeal, Jennifer goes through a long, meditative period of healing before hunting her attackers. In a massive step forward, she begins her hunt by using the men’s own fantasies against them. In Thriller, Madeleine was a silent, explosive attacker; in I Spit on Your Grave, Jennifer uses guile to lure the men to their deaths by assuming the mask of the very fantasies they projected onto her. While facing off with Johnny, after luring him to a remote place and before she dismembers him, he pleads for clemency, blaming Jennifer for her own rape, claiming she ‘led them on’. In this moment, the film captures the exact male ego and refusal of accountability that second-wave feminism sought to dismantle.

In Thriller, Madeleine’s saga is the result of human trafficking; once broken, she is reduced to a sellable commodity for Tony’s profit. Conversely, in Jennifer’s story, the men band together to assault a woman they fundamentally fear. Despite these differing motivations, both Thriller and I Spit on Your Grave conclude on a transcendent, albeit ambiguous, note. As Madeleine and Jennifer depart from the scenes of their final retributions, they move toward an unknown future, having closed a horrific chapter of their lives. Neither film offers clues as to what follows, leaving the audience to reckon with the reality of two women whose identities have been permanently altered not just by the trauma they endured, but by the sovereignty they seized through vengeance.

In Part 3, the focus will shift beyond the 1970s and the immediate wake of second-wave feminism to discuss a compelling variation of the avenging actor: the survivor whose transformation is rooted in mythology. In Indonesian director Sisworo Gautama Putra’s Sundelbolong (1981) and Coralie Fargeat’s Revenge (2017), the survivor transcends her humanity to become a divine agent of retribution. That analysis will explore how those films utilize unique cultural underpinnings to transform the struggle for vengeance into a righteous, holy pursuit, a metaphysical balancing of the scales of justice that transcends the limitations of the physical world.

More Film Reviews

Haunting of the Queen Mary (2023) Film Review – A Disastrous Shipwreck

As a seasoned horror fanatic, I eagerly anticipated the 2023 release of director Gary Shore’s Haunting of the Queen Mary, expecting spine-chilling thrills and a captivating storyline. I grew up…

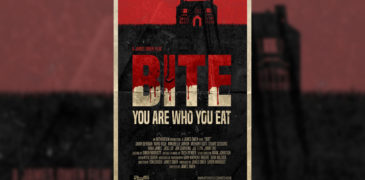

Bite (2022) Film Review – A Hair of the Dog that Bit Me

Bite is a 2022 British horror thriller, written and directed by James Owen, with additional writing from Tom Critch. Although a trained trauma surgeon, James started creating short films around…

The Awakening of Lilith (2021) Film Review – The Excruciating Weight of Loss

Sparked by the death of her partner Noah, Lilith is struggling with her mental health and has succumbed to a deep depression that affects all aspects of her life. Fighting…

Sting (2024) Film Review – Scared of Spiders? You Will Be.

Some Critters Aren’t Meant To Be Kept As Pets “After raising an unnervingly talented spider in secret, 12-year-old Charlotte must face the facts about her pet, and fight for her…

The Final Wish (2018) Film Review – When You Wish Upon A Star

Having just landed on Shudder UK, The Final Wish (2018) is director Timothy Woodward Jr’s third film and boasts a story from Jeffery Reddick, writer of the first two Final…

The Reckoning Review (2020) – Neil Marshall’s Return to Horror

RevBarely a year after Neil Marshall’s first big-budget Hollywood feature, Hellboy (2019), failed to earn him a box office success, he has returned to his horror roots with the much…

I am a lifelong lover of horror who delights in the uncanny and occasionally writes about it. My writing has appeared at DIS/MEMBER and in Grim magazine. I am also in charge of programming at WIWLN’s Insomniac Theater, the Internet’s oldest horror movie blog written by me. The best time to reach me is before dawn.