The horrors of war don’t just end once a soldier returns; in fact, one of the saddest aspects of global conflict is society’s lack of post-care for soldiers. Unfortunately, heroism is only perceived as such when it fits a narrative, and authorities are quick to push human suffering under the rug as soon as it has a negative connotation. Sadly, parades and celebrations certainly don’t carry someone till the end of their life – a life which can be ruined by severe mental or physical trauma. For proof, it is easy to find some truly horrific statistics.

This shameful treatment of our fellow man has spawned some notable entries in the horror genre, with stand out films like 1974’s Deathdream or the ultimate critique of the war as in Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun. While these may not fall into horror in the traditional sense of the genre by being grounded in reality, it would be hard pressed to find anyone who could read Trumbo’s novel without feeling a deep sense of dread and horror.

Regardless of what side of the conflict you are on, it is undeniable that the negative impact on individuals is universal. This leads us to The Caterpillar from the prominent literary figure Edogowa Rampo, a macabre tale of a man who comes back a shell of his former self after serving In the Japanese Army. The Caterpillar would go on to be adapted into film as well as manga, the subject of this article.

Personally, this is one of the most difficult stories for me from Rampo. One of the most accomplished mangaka in the Erotic Grotesque movement adapting the tale had me simultaneously excited and weary to dive in.

A woman is tasked with taking care of her partner, who lost his limbs and ability to speak after getting hit with artillery during the war. Living in a small village, the two are given free rent and a pittance towards financial aid. Unfortunately, as people begin to try to move on from the war, they also begin to pay less attention to the couple. Resentment begins to grow as a sense of duty dissolves into contempt at the existence of having to take care of the physical and mental needs of someone who is no longer recognizable as a human.

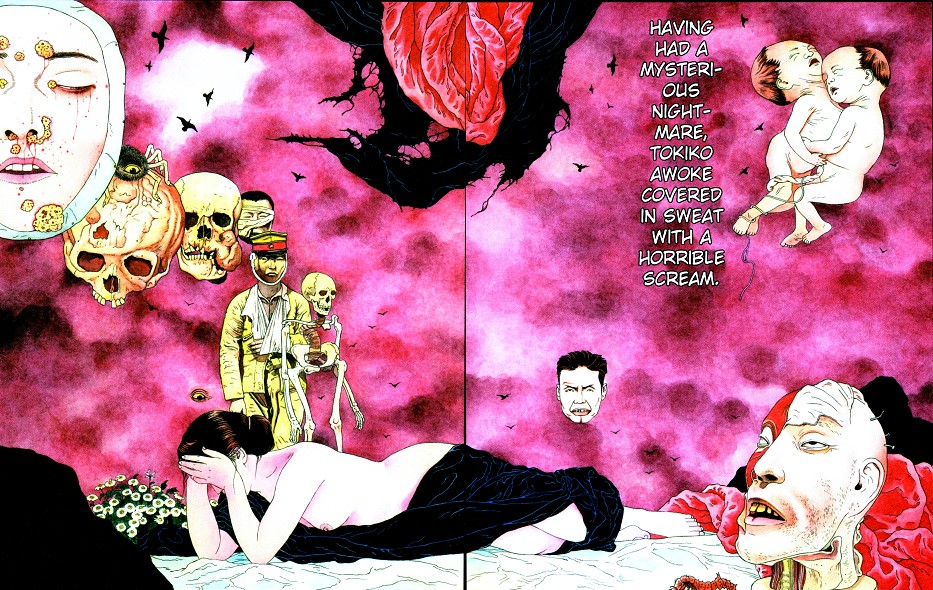

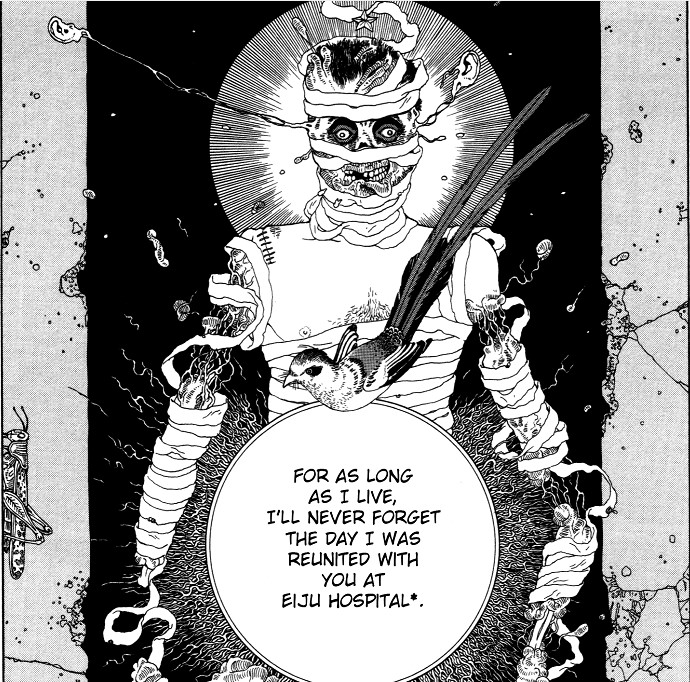

Maruo’s skill as an artist is without comparison, a true master of the craft. In addition, his skill in focusing on erotica and horror makes him the perfect one to adapt such a work that explore both extreme violence and sexual lust. Fluctuating between graphic sex and visions of death on the battlefield, the work is as impactful to its anti-war message as it is mesmerizing in it morbidity.

There are a few panels that are pretty draw dropping, including a nightmare vision of the woman being approached by unknown assailants while laying naked atop a heap of mangled naked corpses – behind her they form a large pillar of dead soldiers. Say what you want about the content, Maruo always knows how to make an impact in any work he touches.

The narrative paired with the art captures the feeling of growing disgust and a sense of abandonment leading to its tragic yet inevitable conclusion. Thankfully, the sensational art of Maruo does not actually distract from the implicit message.

This is a tricky question, as even talking about the work in terms of ‘like’ and ‘dislike’ don’t seem entirely apt for a work of this ilk. Sex and violence in such a graphic fashion is bound to create a degree of dislike on a visceral level. However, when this is the intent of the work, it seems inane to put something down unless the reader themselves has a sensitive disposition that pushes the work more towards pornography than art deserving merit.

It is also possible to nitpick a bit on the material. As far as adaptations of the original go, I prefer the movie from Koji Wakamatsu slightly. Furthermore, if I were asked to recommend the best of Maruo, this title would probably not be my first choice. Although with that said, I really did not dislike anything about this particular project.

Maruo and Rampo are a perfect match, and this is not the only adaptation that the mangaka has tackled of the prominent literary figure. In many ways, Maruo seems inspired by the author not just in choosing to cover but reflecting a deep understanding of the work. If you are fan of either, this is the perfect amalgamation of the macabre, commentary and art. The work also captures how the horrors of war linger long after the parades and praise have lost social importance – a message of importance which will always be relevant.

More Manga Reviews

Jungle Juice Vol. 1 is a sci-fi fantasy manhwa, written by Hyeong Eun and illustrated by Juder. Hyeong Eun has worked as a writer on the webcomic 100 (2020-23), whereas… Junji Itō is easily the most prolific horror mangaka in English translation. Viz Media has made a concerted effort to bring as much of his work to the west as… Chloe Love is a struggling actress, best known for playing Ghost Reaper Girl, the main character of a cult horror movie about a high schooler in a blood-soaked bathing suit… The Summer Hikaru Died is an ongoing (currently at 4-volumes) slice of life/horror Seinen manga, written and illustrated by Mokumokuren. First conceived while Mokumokuren was studying for his exams, the… Manga Diary of a Male Porn Star is an autobiographical account of Kaeruno Erefante’s time in the AV industry. The manga follows Kaeruno’s time from being a cock on screen… I remember the first time I watched Hiroya Oku’s Gantz anime. Let’s set the scene: it was the early 00s and I would hang out with my friends after…Jungle Juice Volume 1 Manhwa Review – A Bugs Life

Sensor (2019) Manga Review – Junji Ito’s Take On Cosmic Horror

Ghost Reaper Girl (2020-ongoing) Manga Review—Action, Humor, and Horror References

The Summer Hiraku Died: Volume 1 (2023) Manga Review – Uncanny Valley

Manga Diary Of A Male Porn Star (NSFW) Review – Learning the Ins and Outs of AV

Gantz (2000) Manga Review: Gore, Sex and a Lot of Feels