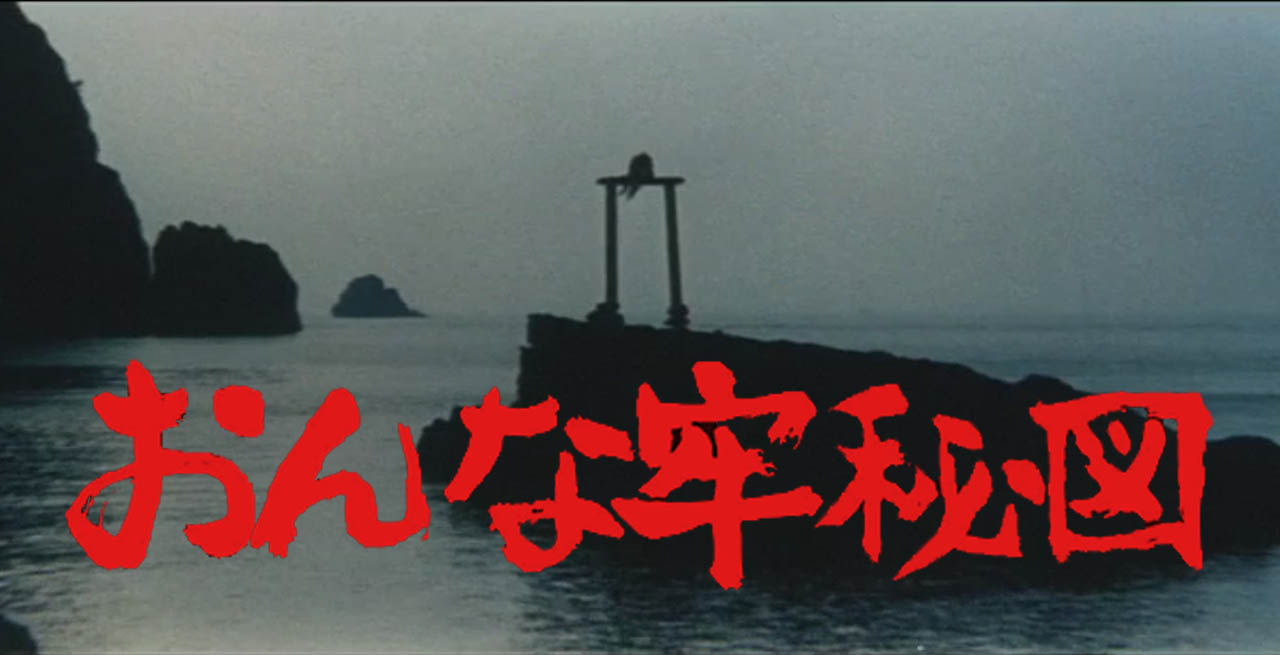

With the turn of a new decade, new opportunities were sought by film studio Daiei. In 1970, Daiei on the verge of bankruptcy, entered into a partnership with fellow struggling studio Nikkatsu, forming Dainichi Eihai. By pooling their resources, the aim was to fight against Toei’s market dominance: by the 1970s Toei had perfected their A&B movie format ensuring four new releases every month. Dainichi Eihai would tackle this directly by pushing forth a massive six films a month. Much of Japanese cinema in the early 70s was largely defined by the exploitation genre as studios fought against TV quickly becoming the go-to source of entertainment, so it is understandable that Daiei’s “ero guro/unique historical drama” line would be revived in the Dainichi Eihai partnership. Island of Horrors would be the first entry in this new era of Daiei ero guro and continues on with the theme of the previous Woman’s Secret series, choosing to return to the popular historical Edo-period prison settings seen in Secret of a Woman’s Prison and Secrets of a Woman’s Prison 2.

Island of Horrors takes place on the “Isle of Women”: a small desolate rock whose sole purpose is to serve as a women’s prison. The island (dubbed “Decapitation Island” by its inhabitants in vein of the punishment for attempted escape) is totally uninhabited except for 11 female prisoners and their 5 jailers. The film begins with three newcomers: Osen (Hiroko Sakurai) – an opium addict, Okiyo (Maya Kitajima) – a card swindler, and more unusually, Isahaya (Masakazu Tamura) – a disgraced samurai exiled to work on the island as punishment. Although, in reality, every inhabitant of the island is an effective prisoner as it is revealed that all of the jailers have been sent there due to a variety of indiscretions against the shogunate. With everyone abandoned on such an inhospitable island, resentment grows strong.

After Osen and Okiyo’s initial meeting with the queen bee of the prisoners – Omasa “the ripper” (Yuki Aresa) – ends in her goons savagely beating them into submission with oars, it is clear that there is no sense of sisterhood amongst the prisoners. Everyone looks out purely for themselves, and Omasa is even plotting to double-cross everyone and seduce the warden, Jingoro (Hiroshi Kondo), to convince him to swap her for another prisoner who is due to be freed. Life on the island is defined by nonstop suffering with mere survival acting as their punishment. On such a barren rock there is no food to be farmed, and the only source of clean water can only be accessed by abseiling down the side of the cliffs to reach a small spring. Once the clean water has been obtained, most of it is used not for drinking but instead for the tyrannical Jingoro’s daily bath. When they’re not gathering supplies, the only other daily duty is backbreaking labour attempting to mine a well out of solid stone in search of a more accessible water source.

Events then take an unexpected turn in the aftermath of a savage storm. When one of the prisoners walks outside the hut the following morning, she finds a woman washed up against the fence. Straight away they can see by her pink kimono that she is no prisoner, and after uncovering her face they are shocked to discover that she is actually a prisoner who was supposedly released a month earlier. The prisoners along with Isahaya, who overhears a conversation amongst Jingoro and the Shogun officials who have visited from the mainland, uncover the island’s biggest secret: no prisoner has ever been officially released. When it is time for a prisoner to be released, the officials, in conspiracy with Jingoro, make false claims that they died prematurely on the island, and instead sell them as prostitutes to passing European merchant ships.

After learning of this secret, events go from bad to worse when a prisoner suddenly dies with hideous black sores over her face. Thanks to Isahaya’s previous dealings with Europeans, he quickly realises that the black death has made its way onto the rat-infested island. With the sudden outbreak, chaos ensues and all loyalties are quickly forgotten as the shogunate officials plot to abandon the island, leaving the prisoners behind along with Isahaya and his knowledge of their secret. With the women finally uniting against their captors, it becomes a desperate fight to reach the shore alive and commandeer the last surviving boat off the rock.

Whilst Daiei and Nikkatsu continued to produce their own films separately within the Dainichi Eihai partnership, it seems that a lot of Nikkatsu’s edge began to bleed into Daiei’s output. Island of Horrors undeniably jumps headfirst into this newfound edginess, leaving behind the more reserved nature of the previous Woman’s Secret films of the 1960s. Director Toshiaki Kunihara, in his debut, commits to the new focus bringing a fair amount of sexualised torture to the fore highlighted by two extended scenes of sleaze and sadism.

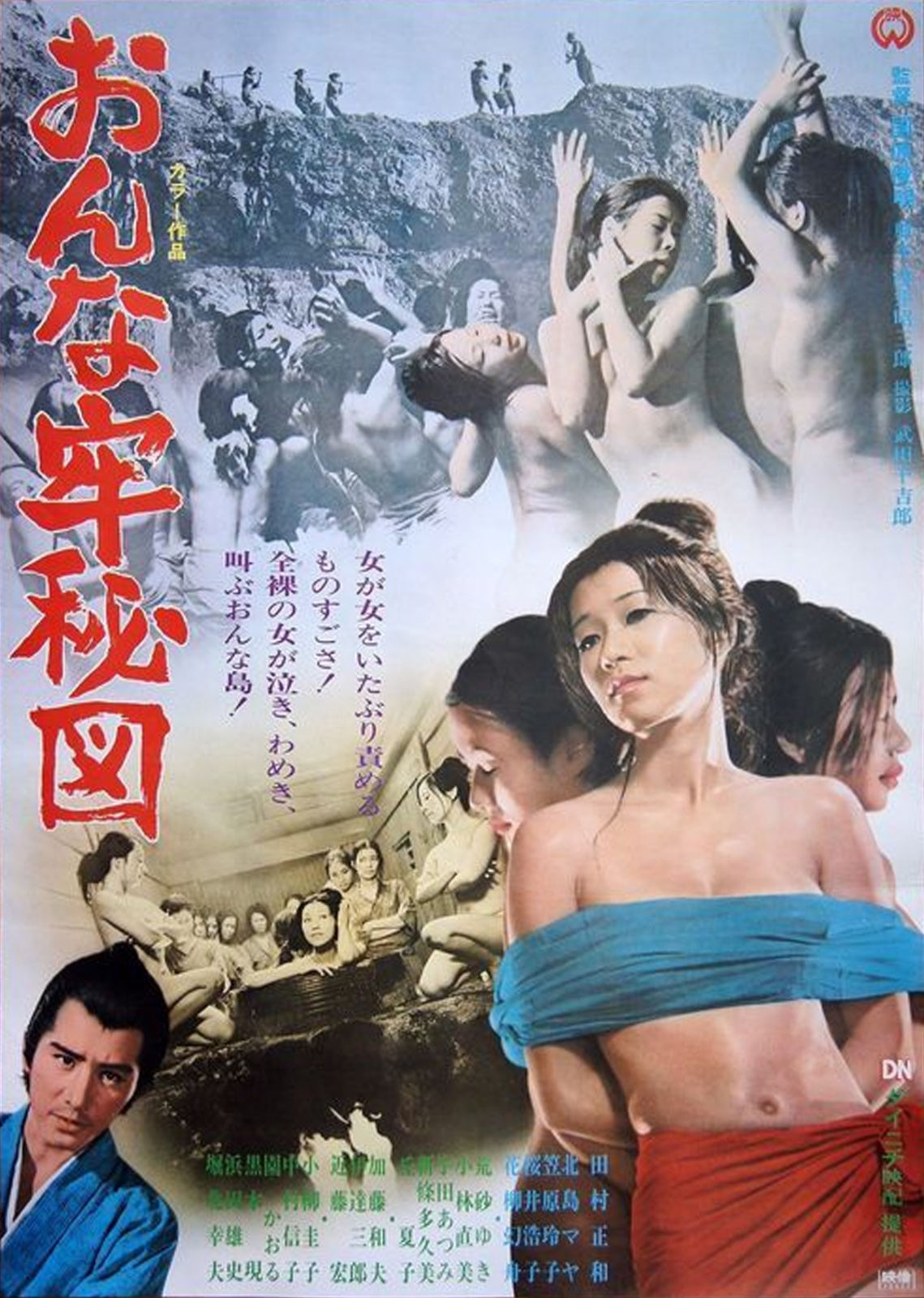

Bringing an atmosphere more expected of a Toei film, the first torture scene (also referenced on the poster) features the women locked into a steam room where the guards then fan the fire and practically cook them alive. It is hard to overlook the fact that the scene is little more than an excuse to have lots of naked sweaty bodies writhing against each other, although with a handy viewing window for the guards, that was always the main purpose of that choice of punishment. The second scene sees Okiyo held down naked against the floor with a crucible of flaming oil suspended above her. The crucible is held in place by a chain placed between her teeth and she is then beaten, forced not to move a muscle lest the oil cascade down over her.

Looking past the initial appearance of these scenes, there is more to them than simple exploitation and they serve to give a window into the psyche of the guards. Whilst it implied that Jingoro semi-regularly selects prisoners to sleep with, the overt sexual exploitation so common in women-in-prison films is notably missing from Island of Horrors. It seems that given the hopelessness of the guards’ situation, as well as their resentment to both the tyrannical warden Jingoro and the shogunate who sent them there, they care little for their own needs. Enveloped by nihilism, their sole pleasure comes not from the prisoners’ flesh but instead from their torture – externalising their own suffering by inflicting it upon another.

Island of Horrors, however, is far more than just a collection of exploitative torture scenes, and Kunihara’s best efforts are put into bringing the setting to life. Clearly given a much higher budget than its predecessors, its greatest feature is the on-location shooting. Kunihara takes full of advantage of this and turns the island itself into just as much of a character as the film’s cast. Island of Horrors is the first film in the Woman’s Secret series to be filmed in colour and it is utilised perfectly to further exaggerate the inhospitableness: exterior scenes are bright and often over exposed, giving the film a harsh, sun-bleached look. The only shelter on the island for the prisoners is a single hut; no bars are required since any escape attempt is suicide. The interior scenes are the perfect antithesis to the blinding outdoors, feeling gloomy and humid with the atmosphere itself providing the perfect metaphor for the frayed relationships between the prisoners.

Even with Kunihara’s best efforts to maximise the unique location, the film is ultimately hampered by Shozaburo Asai’s script. The script itself is filled with kernels of inspired ideas, but they all come too little too late. Even though both the plots surrounding the selling of prisoners and the plague outbreak are filled with potential, they are held back until the final 25 minutes of the runtime where they have no opportunity to develop. The prospect of the plague being a constant threat throughout the entire film is a frustratingly overlooked opportunity which would really add some tension to proceedings; instead, we are left with the first hour depicting little more than petty squabbles between prisoners.

Notably absent from Island of Horrors is Michiyo Yasuda who dominated the previous films in the Woman’s Secret series, playing the lead in every entry. Whilst it is refreshing seeing an entirely new cast, writer Shozaburo Asai completely abandons his tried and tested formula of the previous films (all also written by him) and strangely never commits to a clear protagonist – perhaps concerned that filling Yasuda’s shoes would be too much of a burden, especially with a cast consisting almost entirely of very little-known actresses. In the previous entries of the series, Michiyo Yasuda’s protagonist was key in guiding the audience through the setting and events; without any such connection, Island of Horrors feels unfocused as the audience is never afforded the time to properly explore any one prisoner’s deeper experiences and emotions. The beginning of the film suggests that Osen and Okiyo will be the main characters, but they are quickly dropped almost as soon as they meet the other prisoners. There is undeniably plenty of thought put into each character’s backstories, but they go little further than a few throwaway lines of expositional dialogue.

Given such brief exposure or a protagonist to bounce off of, it is hard for any of the cast to really stand out. Omasa is played with devious and treacherous glee by Yuki Aresa who has little to no regard for anyone but herself. With her small amount of screen time, Hiroko Sakurai manages to create a lot of intrigue in the introverted character of Osen who is struggling with the constant onslaught of aggression from Omasa just as much as her cravings for opium. However, the most complex character of the film belongs to Masakazu Tamura’s Isahaya. Initially arriving on the island humiliated by his exile, Jingoro hammers the point home by admonishing the guards for referring to him with a noble honorific. He soon falls into a spiral of apathy but is gradually reminded of his code of honour by the actions of Jingoro and the guards. Eventually, he is able to redeem himself in a furious final battle in the sake of honour.

Island of Horrors, despite its initial issues, eventually picks up momentum for an undeniably fun final act, packed with plenty of action and drama to make up for the slow start. Despite some great standalone sequences and devilish twists, it has to be said that the combination of events and the extreme setting become just a little too over the top, and the film admittedly ends up feeling more campy than genuinely shocking. Even though it is a clear departure from the more quietly atmospheric Secrets of a Woman’s Prison films that preceded it, Island of Horrors has a great deal of charm highlighted by the sumptuously hostile island setting. Perhaps not the best example of a typical women-in-prison exploitation film, Island of Horrors, nevertheless, comes with just enough 1970s edge to bring an ultimately satisfying take on Daiei’s ero guro subgenre.

More Film Reviews

With Last Night in Soho, Edgar Wright’s latest film, the British filmmaker continues down the path he’s carved with his 2017 ‘Baby Driver‘ – mixing different genres into an extremely… Is There Life After Death? “After Death (2023) is a gripping film that explores the afterlife based on real near-death experiences, conveyed by scientists, authors, and survivors. From the New… Inspired by Nanami Kamon’s original novel, Room 203 is Ben Jagger’s new film that explores one of the most memorable horror genre staples: the haunted property. This trope is always… Satan Claus is an Italian/American low-budget slasher horror, written by Simonetta Mostarda and directed by Massimiliano Cerchi. Well-versed in independent horror, Massimiliano is known for directing such lo-fi additions to… A bizarre blend of Phil Tippett’s Mad God and Dario Argento’s Suspiria, Robert Morgan’s feature debut Stopmotion (2023) is an indie horror film that weaponizes the maddening process of stop… Alongside their dedicated Shorts Showcase (both Canadian and International), the Toronto After Dark Film Festival offers bitesize extras for those attending. Each of the main features is preceded by a…Last Night In Soho Film Review (2021) – Music, Fashion And Mass-murder

After Death (2023) Film Review – What Happens When We Die?

Room 203 (2022) Film Review: Friendship Brings Fresh Air to a Haunted Room

Satan Claus (1996) Film Review – Won’t You Join My Slaying Tonight?

Stopmotion (2023) Film Review – The Magic of Animation

TADFF 2023 Canadian Shorts (Pre-features) [Toronto After Dark Film Festival]

Hi, I have a borderline obsession with Japanese showa-era culture with much of my free time spent either consuming or researching said culture. Apparently I’m now writing about it as well to share all the useless knowledge I have acquired after countless hours surfing the web and peeling through books and magazines.

![TADFF 2023 Canadian Shorts (Pre-features) [Toronto After Dark Film Festival]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Untitled-design-18-365x180.jpg)