Here at the Grimoire of Horror, we’ve reviewed both Jorge Torres-Torres’s Fat Tuesday and Sisters of the Plague, commented on him being one of the most underrated independent filmmakers working today and discussed his documentary-like approach to storytelling. It is then perhaps unsurprising that one of his earliest and most obscure films, FTW, is a blend of documentary and fiction which also makes its location a main character; it might, however, surprise even fans of the director with its unconventional approach and with by how fast it turns into a microbudget masterpiece conveying a deeply unsettling story of grief and ruin.

FTW is a found-footage film focusing on the lives of two Louisiana misfits, Kristopher and Ryan, who turn to violence in the wake of their close friend’s death. Shep “put a plastic bag over his head and blamed the world” one night, leaving his mates unable to cope with his loss. They adopt a seemingly blasé attitude towards death, simply commenting that there is something in the soil related to the high suicide rates in the area. Ryan gets more aggressive than usual while Kristopher, having survived both boarding school and military school, becomes even more detached from reality. They tirelessly pull pranks on each other and engage in acts of destruction. The Unnamed Footage Film Festival where FTW screened at describes it as combining “the heart of Errol Morris with the satire of Harmony Korine in this adolescent romp through above-ground cemeteries”.

FTW deals in themes such as alienation, grief, poverty and a mix of pent-up rage and morbid curiosity. As the movie does seem to be a direct response to Trash Humpers with a bit of Kids thrown in, it would be far-fetched to call Ryan and Kristofer’s behavior nihilistic, or anything other than adolescent. The two don’t really believe that there’s nothing interesting left to experience in the world, or that they themselves have nothing meaningful to discuss. Instead, they refuse to allow anything meaningful to happen to them, by living dangerously and misinterpreting everything. They seek to test the fragile boundaries around them. Both try, and repeatedly fail to find themselves in local myths and beliefs. An extreme poverty version of Beavis and Butthead, the two aren’t prone to sitting on the couch, watching music videos – because they seem to be homeless, they would be more likely to smash any television set with a baseball bat and set it on fire. Torres-Torres has directed similar movies, such as Shadow Zombie, and worked on Hillbilly Wolf, about “a societal misfit / holy boy who lives in a small town in the Bible Belt region of North Louisiana”, but FTW is a perfect calling card for the director, begging to be rediscovered more than 10 years after its release.

The US microbudget cinema has a habit of focusing on maladjusted protagonists. Whether they’re blue-collar workers or living in poverty, they are social outcasts prone to obsessing over minor details, generally built for a bittersweet, emotionally draining or even tragic ending. Some extreme examples of this tendency can be found in films such as Ronald Bronstein’s Frownland, with all its characters being neurotic; Joel Potrykus’s Buzzard, with its couch-potato, amateur con-artist, Nintendo power-glove wearing leading-man, and the works of Jason Banker (a frequent collaborator of Torres-Torres), Toad Road and Felt. If one looks at all microbudget films released between 2007 and 2015, it is hard to find even a handful that aren’t about dysfunctional people leading extremely messed-up lives; watching these characters can be a claustrophobic experience, as these films often employ frantic editing and hit with the force of a Category 3 hurricane.

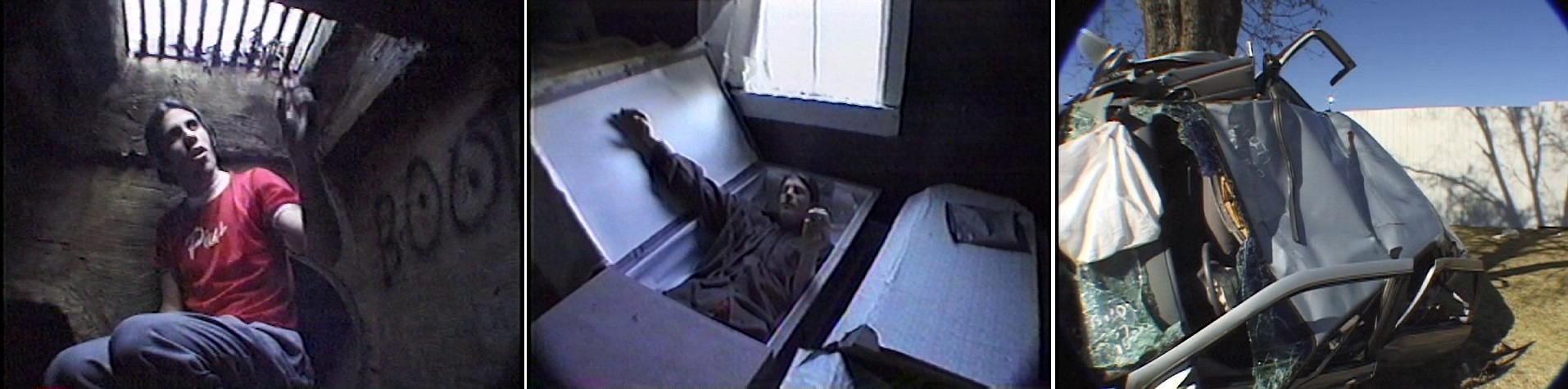

As the two protagonists seem to outdo themselves in morbid experimentation, their pranks morph into real transgressions: at one point, they take over a concert hall and fight a man. They mock death itself by going into the motel room Shep died in and by trying out a child casket, commenting on how it’s more comfortable than the beds they actually sleep in. In a found-footage horror movie, this would be a pivotal moment – their fatal mistake. Here, it’s just another moment in their fraught existence. There seems to be a fundamental misunderstanding of the larger world which defines their language and that of the people around them, and this is where most of the movie’s humor stems from: the narrator undercuts the movie’s homoerotic vibes by hilariously retelling Kris and Ryan’s attempt at proving to each other than they’re not gay. At one point, they conclude that “sperm is life” after recalling a story about samurais supposedly kidnapping young boys. They miss the point behind women’s rights, commenting on “a woman’s right to have a baby”. In perhaps the movie’s funniest blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moment, a man is seen carrying a sign which says “God loved the world so much He gave…John 3:16“, which is… a really postmodern interpretation of the most famous verse from the Bible.

Taking that Bible quote further and shifting the discussion to one about sons, the movie does seem to partially focus on dead-end kids, which is, surprisingly, also where Kris and Ryan seem to draw the line – they do give young boys false hopes and feed them tall tales at times, but they don’t really seem to want to corrupt them. Perhaps they’re still yearning for a childhood lost? In a counterpoint to Jaffe Zinn’s Children, lacking that movie’s lurid ending, FTW is surprisingly caring and gentle when it comes to kids, while emphasizing how tough it is to survive as a young boy in such a disastrous environment.

For a microbudget film, FTW really impresses through its visual techniques and powerful imagery. Told by an unnamed narrator the film employs, but doesn’t limit himself to, VHS aesthetics – it also uses fish-eye views, glitch art, weirdly-pitched, dissonant audio samples and different video filters in order to make each vignette seem like an additional layer of the hell inhabited by Kristofer and Ryan. There is an interlude which feels oddly similar to the nightmarish vision of Calvin Reeder’s The Oregonian. The Trash Humpers chant is reinterpreted here with the use of the Nepal’s Children Choir. While most chapters share an anarchist video tone, (Shep himself is described as “able to collapse society with thought-viruses”) there is an argument to be made that the film actually conjures up what Emmanouil Aretoulakis coined as “forbidden aesthetics”. In his book Forbidden Aesthetics, Ethical Justice, and Terror in Modern Western Culture, Aretoulakis speaks of a whirlwind of images of natural and man-made disasters meant to conjure up an odd mix of repulsion and fascination. The most powerful such image is perhaps that of a cherub cemetery, which along with the aforementioned child casket, speaks volumes of the toll that living in this space takes on people of all ages.

One common criticism of mumblecore, a subset of microbudget cinema, is that it is too “white” and detached from any racial issues whatsoever. Of course, there are exceptions, (Joel Potrykus’s The Alchemist’s Cookbook being one of them) and – whether one considers FTW mumblecore or not – one of the film’s side-characters is a young man, wise beyond his years, a tap-dancing street artist who, during the movie’s climax of sorts, arrives at a strange realization about his role in the world (other characters include a sickly cat owner and his puzzle-obsessed wife). FTW doesn’t really aim at just depicting Kris and Ryan’s lives, but to place them in a much larger context, and for once, minorities are not underrepresented.

By far the best thing FTW does is provide a kaleidoscopic view of life in a small Louisiana town where life grows surrounded by disease and rot. There are fairs, including horror-themed ones, where people paint their faces or sing Celine Dion songs. The church, psychedelic mushrooms, hints of gun violence, and a post-9/11 dread share an equal hold on people’s lives. Education levels are low, healthcare is poor to non-existent, everyone has to fend for themselves. Kris and Ryan’s usual haunt is underneath a car wreck, (Shep’s ghost is still rumored to appear there), and there are forlorn buildings, ruined architectures of despair, dead animals everywhere. Kris and Ryan only amplify, through their actions, the feeling of “point of no return” having been crossed in times long past, of moral wasteland, the movie gaining the proportions of a travelogue, with its twin “Gullivers” dwarfing everything and everyone in a land of the lost.

Of course, left with nothing better to do after having braved the “cursed” motel room, Kris and Ryan eventually run out of adversaries. The narrator’s nature is finally revealed and the ending hits not by doing anything exceptional in terms of plot twists, but by mixing up the aforementioned “forbidden” feeling with that of a terminal diagnosis. With FTW, fans of Jorge Torres-Torres will be rewarded with an obscure masterpiece, and newcomers to his work will no doubt appreciate his skill at creating a suitably grimy microbudget looking glass. As a recent Indiewire article shed some light on how tough it is nowadays for DIY movies to find distribution, it’s worth mentioning that Jorge Torres-Torres has made many of his movies available for free on his Vimeo channel, including his 2021 movie “Night of the Rumpus”. Perhaps it would be wise for such movies to consider Kentucker Audley’s NoBudge platform – at least as a temporary avenue – as last year it made the move to a subscription-based service, but the current situation makes festivals like the Unnamed Footage Festival a vital resource for independent filmmakers to make themselves heard.

FTW is Screening as Part of the 2022 Unnamed Footage Festival

More Film Reviews

Anyone who’s been in a car accident understands disorientation; the lack of clarity of what just happened, the realization that time does indeed slow down, it’s not some old wife’s… Confessions (Kokuhaku in Japan) is a 2010 revenge thriller based on Kanae Minato’s critically acclaimed debut novel. From director Tetsuya Nakashima who also produced the visually bubbly ‘Kamikaze Girls‘ and… Ari Aster. Jordan Peele. Robert Eggers. These modern-day directors have transformed and elevated current horror trends by pouring clear passion, love, and vision into each film. Danny and Michael Philippou’s… With the year drawing ever closer to its conclusion, we cast our mind’s eyes back on the monumental releases over the past 12 months. Join us at Grimoire of Horror… It’s no secret that since the original and beloved Predator hit cinemas back in 1987, the franchise has seen a steady decline in quality, with each subsequent entry somehow managing… Being mostly an American tradition, fraternities seem to be full of real life horror stories due to the harsh hazing rituals regularly to new pledges. These organisations seem to be…On the 3rd Day Film Review – Fantasia Festival 2021

Film Spotlight: Confessions (Kokuhaku) [2010]

Talk to Me (2023) Film Review: Psychological Possession Packs a Punch

Grimoire of Horror’s Top Films of 2023

Prey (2022) Film Review – Predator is Revitalized

Hell Night Film Review – A Hybrid of Slashers and Haunted Houses

![Film Spotlight: Confessions (Kokuhaku) [2010]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/confessions-header-365x180.jpg)