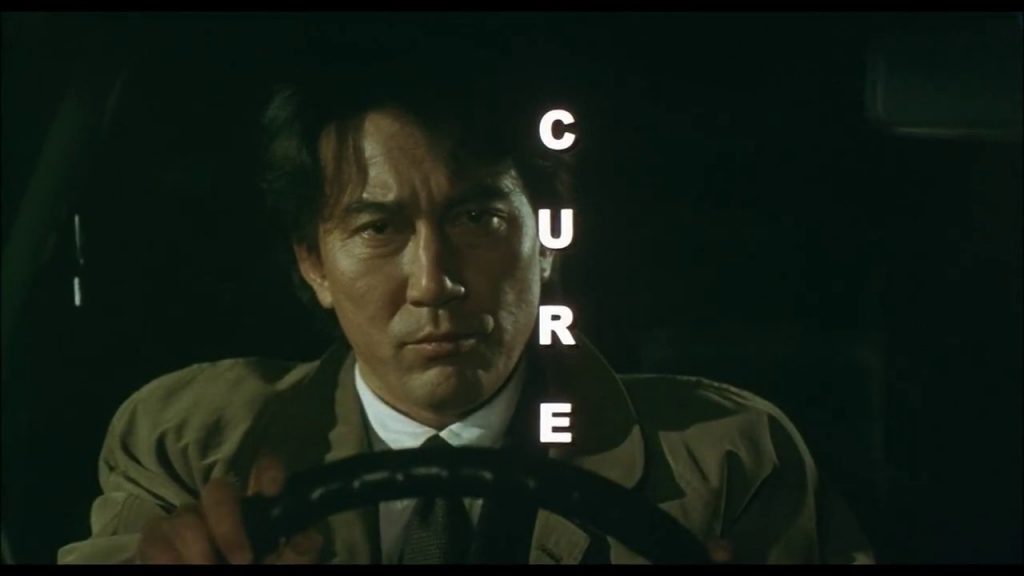

In this short article, I want to write something about Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure (1997). Yet, I do not want to present a common review, but I want to offer a somewhat more poetic piece on the rather scandalous truth of Kiyoshi’s mystery-horror masterpiece.

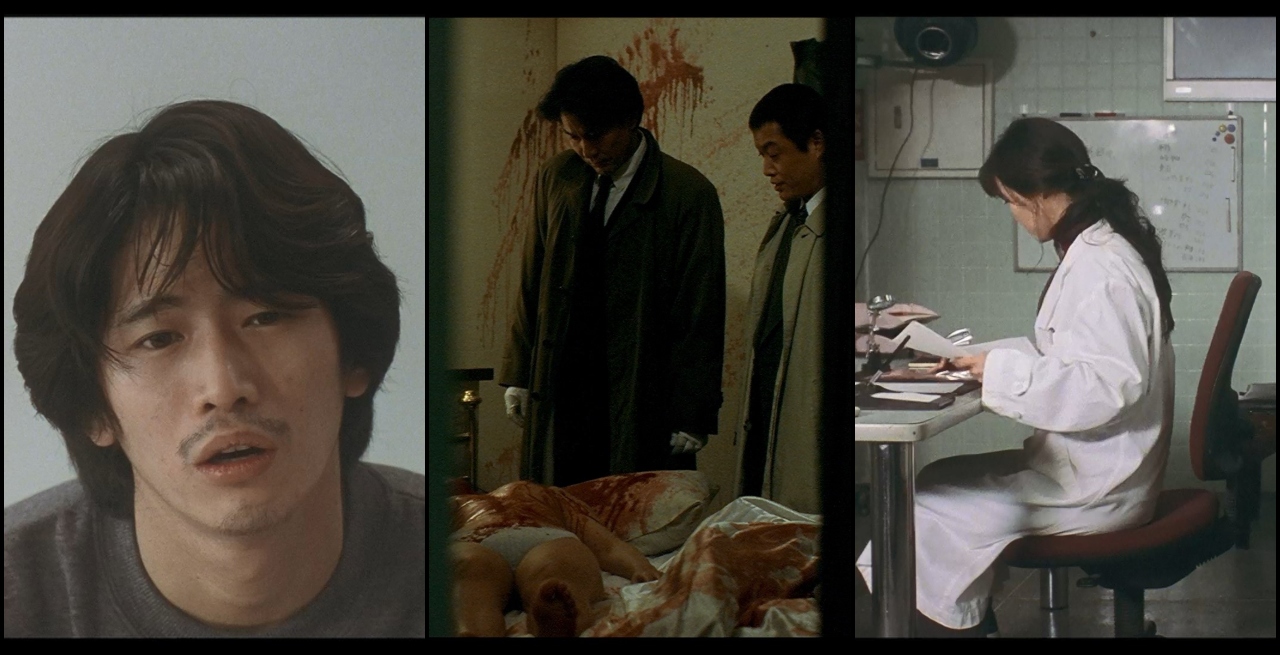

Cure follows Detective Kenichi Takabe (Koji Yakusho) as he is tasked to investigate a string of strangely similar and excessively violent murders. He teams up with Sakuma (Tsuyoshi Ujiki), a psychologist, to try to make sense of these puzzling crimes. After another woman is murdered similarly, Takabe and Sakuma start investigating Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), a rather strange and mysterious man with mesmeric powers.

In Cure, Kurosawa expertly plays with the notions of truth and lie in his narrative. Do we want to know the truth of our humanity? Can we, once it is revealed, accept it? Or do we try to cover this ugly thing up, locking it up in the deep caverns of our subconscious?

The mesmeric power of Miyama depends on the very deception that marks our conscious life, and depends on a truth that we, as humans, do not want to accept as being our own. There are certain desires, certain thoughts, and certain forms of pleasure that are at odds with our sense of self. Rather than welcoming these dark desires as being our own, we frantically try to imprison them in the musty and forgotten chambers of our mind.

But what kind of desires do we hide from ourselves and from the others we interact with? Nothing other than desires that are destructive, destructive to us and those that surround us. The desire to destroy one’s flesh and the desire to violate the flesh of another human being.

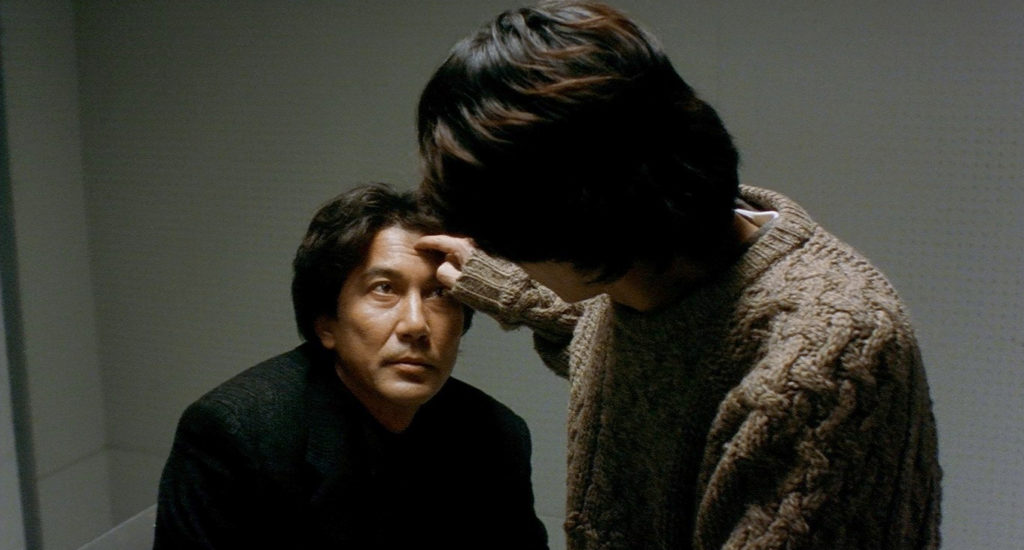

Miyama’s mesmerism preys on people who are unable to come to terms with their violent desires, feasts on those people who are unable to release their violent desires from their subconscious prison and decriminalize them. Miyama preys on those people who are content in living a harmonious lie, a lie where there is no place for the confronting truth of one’s humanity. With his mesmerism, Miyama succeeds in forcing people to act out this truth, he forces them to act under the violent desires they so carefully hide from themselves and others.

Everyone, at least at the level of their desires, is a violator – this and nothing else is the horrifying and uncomfortable truth of Kurosawa’s Cure. Yet, most people refuse to acknowledge it. They reject this truth without realizing that the act of ‘being entirely honest with oneself’ is the only cure, the only defense against Miyama’s mesmerism.

The very reason why Miyama fails to force Takabe to become violent, to become murderous in line with his unconscious desires, is because he accepted the desire to kill his wife (Anna Nakagawa) as being his own. Takabe is immune to Miyama’s mesmeric attacks because his unconscious prisons are empty. After all, there is no imprisoned desire to exploit and hypnotize him with.

Kurosawa’s Cure confronts the audience, in a mesmerizing but rather scandalous way, with the violence that inherently marks the desires that linger in their unconscious – the ending of the narrative reaffirms this rather cryptically. Yet, Kurosawa goes further by revealing the simple yet difficult-to-realize cure to our peaceful deception, to our refusal to acknowledge the aggressive monster that lies beneath our friendly smiles: Honesty with oneself and the ability to accept the horror of our desires.

To read more film analysis from Pieter-Jan you can head over to his official site psycho cinematography

More Film Reviews:

The Quantum Devil is a 2023 American sci-fi horror, written and directed by Larry Wade Carrell, with additional writing from Zeph E. Daniel and Stephen Johnston. Beginning his career as… Forced to move when her mother gets a new job, a teenager called Sol has to face dangers ranging from power outages, bullies at a new school, the worrying behaviour… Proposing itself as an intimate look at a killer, Eri’s Murder Diary (2021) caught my attention among the many titles at Japan Film Fest Hamburg. Directed by newcomer Koji Degura,… Island of Death (Ta Paidia Tou Diavolou) is a 1976 exploitation horror film written and directed by Nico Mastorakis. Most notable as the founder and owner of independent film studio… The Phoenix Lights might be one of the most intriguing pieces of UFO conspiracies on the internet. On March 13, 1997, thousands of people spotted the formation of unidentified lights… Inherit the Witch (2024), directed, co-written by, and starring Cradeaux Alexander, is an ambitious attempt at psychological horror through means of generational trauma. Filmed almost entirely with handheld cameras –…The Quantum Devil (2023) Film Review – Into the Quantum Realm

The Night Belongs to Monsters (2021) Film Review – Argentinian Teen Outsider Drama With A Supernatural Edge

Eri’s Murder Diary Film Review – The Broken Mind Of A Killer

Island of Death (1976) Film Review – Horror on Mykonos Island

Phoenix Forgotten (2017) Film Review – Memorable or not?

Inherit the Witch (2024) Film Review – An Overall Disappointment