After contributing to periodical manga magazines such as Manga OK from the mid-60s, the ever-ambitious Taro Bonten would decide to create his own bespoke gekiga magazine in 1969 named Black Ace. However, this wouldn’t be just any normal magazine and would seek to recreate the mystery genre started by kasutori magazines in the late 1940s. Kasutori magazines were best known for a mix of eroticism, surrealism, and horror in a single issue, creating a very weird vibe referred to as “mystery” – perhaps taking its name from the titles of popular kasutori publications such as Mysterious Magazine and Bizarre.

Whilst at the time there were magazines aimed at specific audiences, it was almost unheard of to have one dedicated to such a specific genre. Black Ace is a testament to Taro Bonten’s work ethic; rather than just settling into the role of editor, he would also paint the covers and write an original horror story for every issue, all whilst writing the serialised manga “Konketsuji Rika” for Weekly Myojo magazine and also working as a tattoo artist. Being a manga artist himself no doubt helped him attract talent to the magazine and with extensive contacts in the industry, Black Ace had some of the crème-de-la-crème of 60s gekiga writing for it.

Like American comic books at the time, the funding and turnover for manga magazines came not from individual sales but from advertising revenue. Needless to say, companies were only willing to part with their money to advertise in magazines that were guaranteed to get the maximum number of readers seeing their ads – a weird magazine dedicated to a niche genre was never going to get the same attention as broader popular titles such as Manga Action and Weekly Manga Times . Horror was a notoriously difficult genre to sell due to this and horror artist Kanako Inuki mentioned recently that even Shigeru Mizuki (also a contributor to Black Ace) struggled to get their manga GeGeGe no Kitaro(possibly one of the most famous and popular horror manga ever created) published in magazines. If GeGeGe no Kitaro was struggling, then Black Ace had little to no chance. Taro Bonten seemingly knowing the stigma that horror manga faced was reluctant to go into too many details when seeking initial investment for the magazine- at one point even having to tell a white lie and describe it as a tattoo-focused cultural magazine.

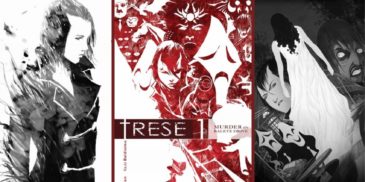

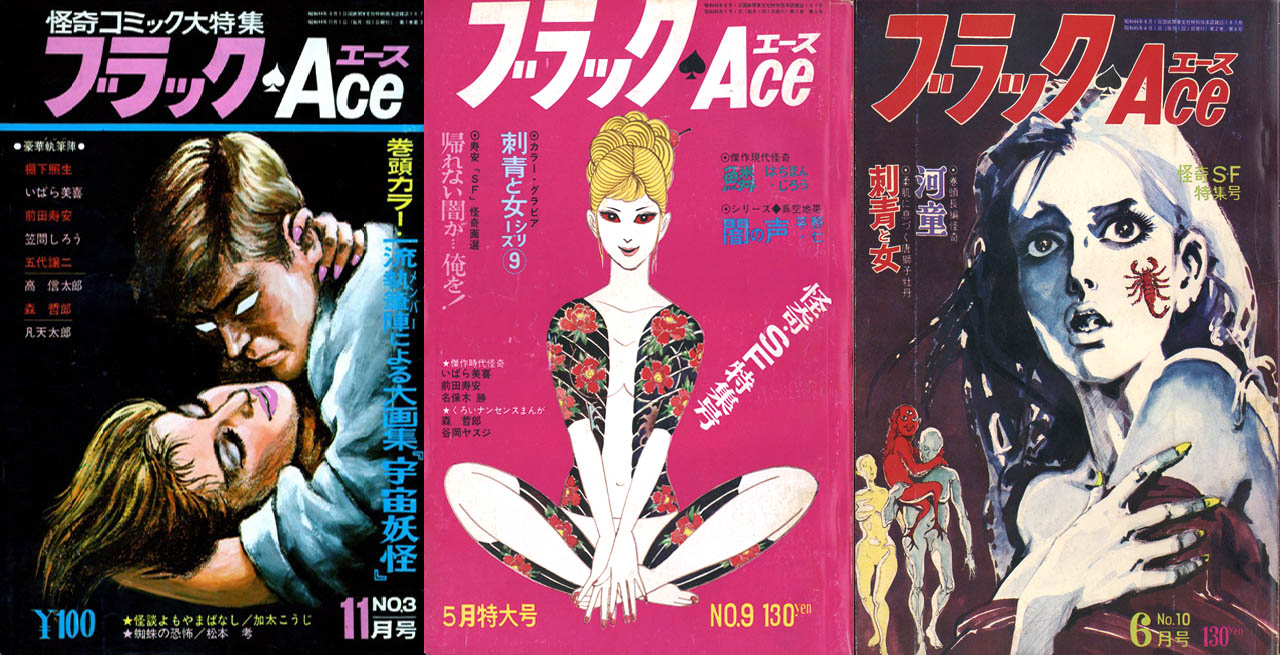

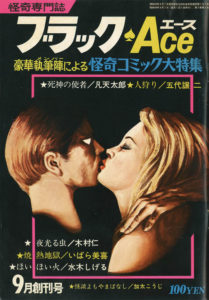

Despite the odds stacked against it, Black Ace‘s first issue was published in September 1969. Publishing the magazine was only the first hurdle, however, and lacking the dedicated distribution network of the large publishers it struggled to really get the attention it deserved. That being said, the magazine itself was incredibly well received and it even won the “Gekiga/Manga Rookie of the Year Award” with horror maestro Kazuo Umezu, along with other top writers Sanpei Shirato and Teruo Tanaka on the selection committee. After ten monthly issues running until June 1970, Black Ace was sadly forced to call it day after Taro Bonten ran out of money to fund it. A similar magazine Black Punch would emerge in 1970 with much greater success supported by a larger publisher, though it was more centred purely around horror – best known for publishing the works of Ichiro Iijima. Thus with the demise of Black Ace, the mystery genre also disappeared again almost as soon as it was resurrected.

Due to the limited print run and a renewed popularity of Taro Bonten, copies of Black Ace rarely come up for sale nowadays, and when they do, sell for extremely high prices. Fortunately, I’ve managed to get a copy of the first issue that we can have a closer look at.

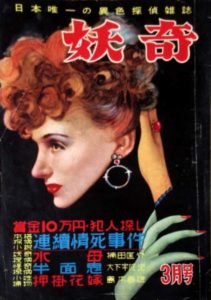

Already from the cover, we can see that it is no ordinary gekiga magazine and there is no mention of it being dedicated to manga save for the tagline “a special feature on mystery comics by extravagant authors”. Clearly invoking the kasutori magazine style, it is a mix of horror with a certain degree of sensuality which reminds me in particular of the cover for Mystery magazine from 1952. This style of cover would last for two further issues before it was changed to the more typical style of a sexy mascot.

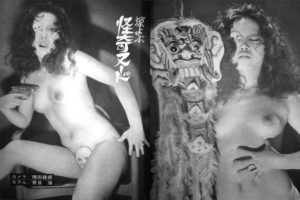

On the first pages, we come face to face with one of the more unique features of Black Ace – here we have model Umi Aome appearing as some kind of voodoo priestess, complete with a skull eye patch, skull thong, and a shaman’s staff. She is the embodiment of the mystery genre – sexy, scary, and very very strange. Further photos from this set would appear throughout the magazine, almost like she is some kind of guide for the reader. Whilst it was very typical for manga magazines to feature topless photos of glamour models, none of them were taken especially for the magazine (they have often licensed pictures of random western models), and certainly, none of them were themed like these. From the very first pages, the tone is clearly set for the entire magazine and announces that this is not your average manga rag.

Our first story comes courtesy of Taro Bonten: “Messenger of the Grim Reaper” is a tale of three sinners – a gangster, a killer, and a woman attempting suicide, who after a near-death experience encounter the grim reaper. Once transported to the edges of hell in a horse-drawn hearse, they desperately try to find a way back to the world of the living for one last chance after having learned the consequences of their actions. The story is very reminiscent of the horror anthology films released around the same time such as “ Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors” which often featured a small group of strangers with seemingly unrelated experiences all brought together to learn a final horrifying lesson.

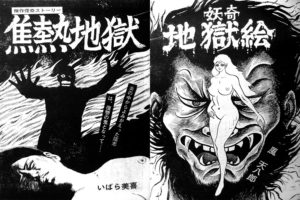

R – “Strange Hell Painting” (妖奇地獄絵) – Tenhachiro Kaze (風天八郎)

Other particularly notable horror stories from this issue are “Fiery Hell” by Miki Ibara and “Strange Hell Painting” by Tenhachiro Kaze. “Fiery Hell” is a masterful spiritual revenge story: after an ignorant couple decides to desecrate a Buddhist shrine by having sex in a temple, the karmic gods are quick to act and cause the man’s house to burn down the following day with him inside. He survives the inferno but is horribly burnt and disfigured; after months of recovery he is able to re-enter society, however as a side effect of the burning, anything he touches with his bare hand’s bursts into flames. During his recovery, he reads that his lover has moved on without him and has married another man. Motivated by anger and also a desire to get his lover back, he seeks them out and ends up attacking her new husband, disintegrating his head with his fiery touch. He then takes his ex-lover to bed and in an ill-judged act of cunnilingus, discovers that his lips also cause burning. With a final sick twist of karma, her vagina is incinerated and the man’s final punishment is realised.

“Strange Hell Painting” follows the somewhat common story of an artist so obsessed with his work that it borders on insanity. Pursuing the perfect nude portrait of his muse, frustration gets the better of him and so begins his descent into evil. This culminates when, after slashing yet another failed painting, he turns the knife on his muse brutally mutilating and murdering her. Rather than feeling guilt, the act of murder brings him relief and gives him the inspiration he needs to be able to complete his work – but at what cost? Once the completed painting is displayed in a gallery, the paint begins to run, disfiguring the subject and revealing the true form of her corpse. As people look on in horror a sorrowful groan emanates from the painting, seemingly imbued with the soul of the artist’s victim.

It is tempting to think what might have been if Black Ace had continued publication, but the matter of the fact is that horror magazines never gained any proper foothold in such a competitive market- even Black Punch despite running for thirty issues is still almost as hard to track down today as Black Ace. That’s not to say horror manga wasn’t popular – Hibari Hit for example had great success almost exclusively publishing standalone volumes of horror manga, though it seems that periodical manga magazines were just a step too far for the genre.

More Manga Reviews:

Jungle Juice Vol. 1 is a sci-fi fantasy manhwa, written by Hyeong Eun and illustrated by Juder. Hyeong Eun has worked as a writer on the webcomic 100 (2020-23), whereas… HoloX Meeting! is a two-volume comedy manga series, written by Omcurry G. K. and illustrated by Anmitsu Okada. The manga is based on COVER Corp.’s 6th generation of V-tuber talent… Indonesian comic creator/artist Azam Raharjo takes a look at the cosmic evil behind a company’s quick rise as their new venture in the restaurant industry sees uncanny success. While the… Higurashi: When They Cry – GOU is a 2-volume psychological horror manga, written by Ryukishi07/7th Expansion and illustrated by Tomato Akase. Ryukishi07 is a Japanese author, artist, and representative of… June 10th, 2021 marked the release of Trese on Netflix, an animated series based on a Filipino Komik of the same name. The anime has been having impressive traction on… Note: This review covers Volume 1 What This World is Made Of is a three-volume psychological action mystery manga, written and illustrated by legendary mangaka Shin Yamamoto. Having created a…Jungle Juice Volume 1 Manhwa Review – A Bugs Life

HoloX Meeting! Vol.1 Manga Review – V-Tuber Supremacy

The Consultant (2022) Comic Review – Cosmic Horror in the Office

Higurashi: When They Cry – GOU: Volume 2 (2023) Manga Review

TRESE Graphic Novel Review – A Success of Filipino Horror

What This World is Made Of Vol. 1 (2021) Manga Review – A Highly Kinetic Piece of Work

Hi, I have a borderline obsession with Japanese showa-era culture with much of my free time spent either consuming or researching said culture. Apparently I’m now writing about it as well to share all the useless knowledge I have acquired after countless hours surfing the web and peeling through books and magazines.