Following WWII, there would be a shortage of decent alcohol and before long bootleg, shochu liquor, referred to as kasutori (effectively Japanese moonshine) began to circulate. Being made from whatever ingredients people could scrape together, sometimes even toxic chemicals, kasutori alcohol soon developed an extremely poor reputation in society, with widespread cases of blindness and even death caused by the drink.

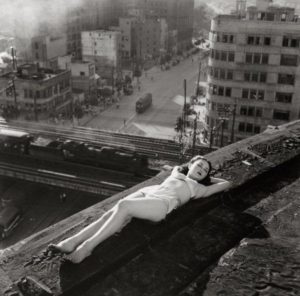

It was this term that would be used to refer to a post-war culture emerging in Japan shirking traditional conservative Japanese values in favour of sexual liberation, hedonism, and to an extent nihilism; portraying it as base and sleazy, like the reputation of kasutori alcohol. After the terror of war and witnessing much of what they loved destroyed, it was no surprise that many Japanese people developed a certain carefree and almost apathetic attitude with the fickleness of life exposed to them first-hand. If everything you worked for could be vaporised in an instant, why waste precious time adhering to archaic values? Japan would also be under American occupation until 1949 and there was very much a sense of limbo in everyone’s lives – people could not focus on rebuilding and returning to normal with the Americans forcing their view of what a modern Japan would look like, both politically and through various sanctions along with demilitarisation. Whilst there was a certain degree of benevolence to this treatment, many people would have no doubt felt that their world was being controlled by this external force and there was no real motivation to take responsibility for one’s own life.

The attitude at the time for many was that of distraction, focusing on work, and treating life more introspectively to avoid the depression and despair experienced after the war. It is no surprise that this period would experience a massive explosion in the arts, with many putting their efforts into creative endeavours. One such distraction for many would come in the form of kasutori magazines – like kasutori culture, these magazines would be named after the alcohol.

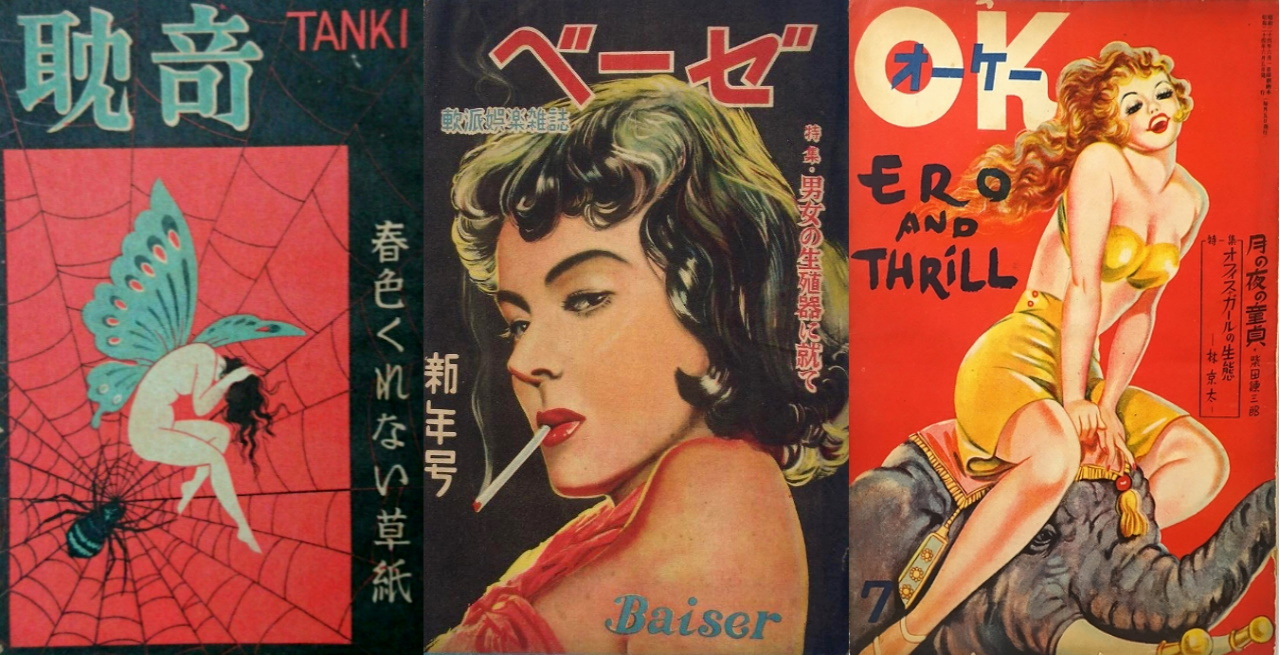

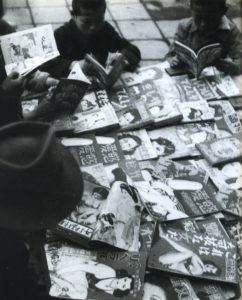

First appearing in 1946, they would be the ultimate expression and introduction to this new post-war culture with frank and explicit articles on sex as well as popular culture, art, and literature. Printed on extremely low-quality pulp due to heavy paper rationing at the time, both the appearance and controversial contents mirrored the bad reputation surrounding kasutori alcohol.

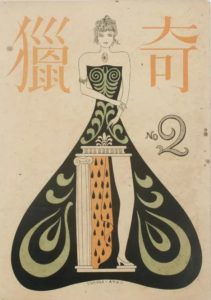

Defining an exact genre for kasutori magazines is quite a difficult task since the contents of each are incredibly diverse, with the editor’s vision and whims making each issue very much its own piece of art. That being said, the magazines were known first are foremost for their sexual content, and this where a lot of their demand came from. However, part of their appeal certainly originates from their fluctuating content – unsure of what would be inside the next issue. The marketing embraced this uncertainty with titles such as “Bizarre”, “Strange”, “Wacky”, “Mysterious”, and so on. This mixture of genres gave the magazine a unique and weird vibe that is difficult to define. With one page talking about sex whilst the next diverging some unrelated surreal encounter, the tone blends together into a strange feeling of almost erotic horror or even perversion. This collective genre would come to be referred to as “mystery”, possibly as a reference to the titles chosen for the magazines.

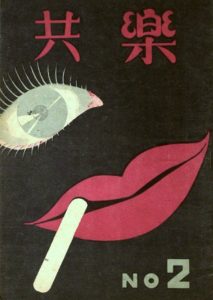

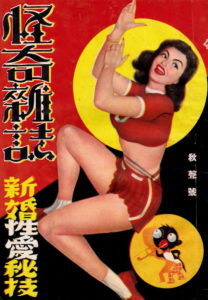

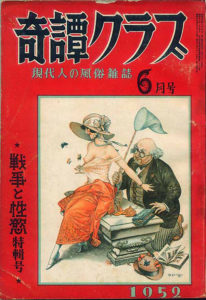

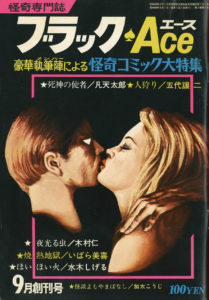

The aspect key to the appeal of the magazine and which continues to prove popular nowadays was the gorgeous cover art. Early magazines from 1946-48 would explore a very avant-garde style, building on the ero guro publications from the 1920s and showing that despite their reputation, the magazines were far from being devoid of artistic merit. Many popular artists such as Seiji Togo would cut their teeth on kasutori magazines. Whilst this matched the mysterious vibe of the magazines, the general aesthetic would later shift into a more conventional pinup style for the latter half of the decade as American culture became more accepted and reduced censorship allowed for open depictions of scantily clad women.

One of the first kasutori magazines to settle on a consistent format, which would be used as a prototype for many of its peers going forward, was “Bizarre”, first published in October 1946. The magazine would feature short stories, both romantic and humorous as well as essays on sex. Issue 2 of “Bizarre” would go down in history for being the first kasutori magazine to be banned with the articles “Mrs. H” (the supposedly true story of a young man who had an affair with the wife of the executed war criminal “Colonel H” during the war) and “Dynasty Amourousness and Humour” specifically targeted for their contents and illustrations. No specific details were given of the ban, so presumably, authorities took issue with both the political sensitivity and the mere existence of the magazine, deciding to make an example of it as an attempt to deter other publishers. However, given the already underground nature of the magazines at the time, it soon entered the black market at a quadrupled price, and the gained notoriety ensured that this specific issue would be reprinted throughout the decade.

After “Bizarre” set the blueprint, most of the following articles would feature in a typical kasutori magazine: romance fiction, often accompanied by an illustration; sex/romance confessions; essays on sex/sex tips; and stories of strange or surreal encounters. One of the benefits of Japan’s American occupation would be an exposure to western culture, the influences of this can be seen plainly in kasutori magazines with many of them featuring pin-up style covers and perhaps most importantly the portrayal of kissing.

Ever since the 19th century, the physical depiction of kissing was outright banned and the act itself outside of the bedroom was seen as abhorrent and sordid. The fact that western culture treated kissing as less taboo was initially seen as shocking and the members of the first Japanese embassy to the United States in 1860 regarded such acts as “unbearable to look at.” This would later become a perfect example of the importance of Japanese imperialism, with many conservative thinkers and politicians in the 1930s using it as a beating stick for Western sinfulness. In 1930 nationalist critic Ikezaki Tadataka would define modern American life as “pleasure-seeking” and would go on to compare Americans to “the barbarians who found the supreme pleasure in monetary, sensual excitements.” Kissing would be one of many ways that kasutori magazines rejected Japanese censorship in the Showa era with both the covers of magazines depicting the act as well as illustrated romance stories inside.

Obviously, the focus on sex was important for people seeking to fill post-war dejection with pleasure, although the articles of strange encounters also seem to be a facet in many people’s psychological recovery. In his book “Post-War Meaningless Flowers: Kasutori Magazines”, Go Watanabe posits that instead of them being a deliberate attempt at horror, they are instead a reflection of the experience of war. During the war, it would have been common for people to see bodies on the streets after air raids and attacks, so the bizarre stories in the magazines are possibly an attempt to attribute paranormal and surreal explanations to events that may normally cause upset and stress to people trying to put the war behind them. These stories would be as much a form of escapism as the raunchy illustrations and sexual articles.

Another significance of kasutori magazines, which gives a window into the culture at the time, was their target audience. Whilst it would be easy to assume at first glance that these are men’s magazines, they were very popular with women much to the contrary. Showing that sexual liberation spread beyond gender divides, many magazines, along with romance stories clearly written to appeal to women, would also feature frank and graphic sex articles intended for female readers. As an example, one issue of “Mysterious Magazine” features a his and hers guide to sex with a list of tips for men and women to improve their sex lives.

One somewhat amusing observation is that, despite sexuality being more open than ever, the nature of the articles still reflects a certain conservative mindset. Many magazines would feature Penthouse-style confession articles, where people would submit stories of sexual experiences, though the most popular of this type of article was the wedding night confession. Perhaps to almost every culture worldwide for millennia, the consummation of marriage is seen as the least sinful act of sex that people can perform. Clearly, as much as people were accepting the freedoms of this new open-minded culture, marriage was still seen as the ultimate goal and a spouse as the best sexual partner one could have.

One of the defining aspects of kasutori magazines, their diversity, would eventually prove to be their downfall. When they first appeared, paper rationing undoubtedly pushed publishers to include as many different subjects as possible in one magazine to appeal to a large customer base and fulfill the needs of several different genres in a single publication. However, by 1951, paper rationing was beginning to ease and this is when we see the rise of more specialist magazines focusing on the individual topics present in kasutori magazines. Magazines like “Kitan Club” and “Liberal” would focus on the more outrageous sexual aspects often specialising in S&M culture; “Married Life” would focus on the sex tips for couples and women’s interest articles; “True Story” would focus on sexual confessions and romance stories; and “Rear Window” would focus on noir pulp fiction. A handful of kasutori magazines, such as “Baiser”, sought to hang on. Using their diversity to branch out into becoming a more general interest magazine, with articles such as film reviews; although they did not last past the mid-50s.

Another hindrance for kasutori magazines was their low-quality pulp paper, which, although fine for printing text, did not lend itself well to detailed images. Any illustrations included had to be limited to quite crude line drawings, and it was almost pointless to include photographs. With normal paper entering general use again and the Japanese government almost totally abandoning any attempts of censorship by the end of the decade, it was unsurprising that magazines like “Kitan Club” became so popular since they could print actual nude photographs.

Unfortunately, kasutori magazines are almost forgotten nowadays, even in Japan, regarded as little more than curiosities of a bygone age. There is also the fact that the low-quality paper they are printed on does not age well, so there are few surviving magazines available today. Obviously, the people who read them at the time would be around 100 years old now and are unlikely to be using the internet, so discussion of them from that point of view does not exist.

To a modern reader, the articles are fairly uninteresting with many things deemed shocking in the ’40s considered commonplace nowadays – your average copy of Cosmopolitan is far more explicit than even the most outrageous kasutori magazine. So unless someone has a dedicated interest in the culture of that period, they are not the type of thing that they will buy out of casual interest.

Kasutori magazines do carry a legacy, however, and one piece of direct influence they would have on later culture is the term “pinku” used to refer to softcore films. Kasutori magazines were sometimes known as “peach-coloured books” as a reference to the brown, almost pink hue of the pulp paper as well as a metaphor for the sexual content. Before long, “peach-coloured” or “momoiro” became the slang term for all things raunchy and would outlast the magazines themselves. By the late ’50s, with the mixing of American culture and English slang terms being used amongst the youth, “momoiro” was soon replaced by its English-derived counterpart “pinku”.

Over the years, there has been little interest in reviving the genre of the “mystery” magazine, meaning that the culture of these magazines is firmly cemented in the 40s with no modern interpretation. Possibly the only attempt to revive this genre would come from Taro Bonten in 1969, with his magazine “Black Ace“. “Black Ace” would be a gekiga magazine focusing on a mix of horror and erotic manga, not at all dissimilar to the content of kasutori magazines, just in manga form, perfectly capturing the “mystery” vibe that came with combining the bizarre with the erotic in the same publication. Unfortunately, it seemed that at the time, there was no demand for this type of magazine and only 10 issues were made in very limited runs.

Despite being relegated to little more than esoterica, these magazines played a very important part in laying the foundation for the freedom of artistic expression that Japan enjoys to this day. Kasutori magazines were at the absolute forefront of pushing the limits of post-war censorship and it is very possible that without their constant pressure, the artistic landscape of Japan would be very different. With their frank and explicit articles, the magazines would champion the culture of sexual liberation developing at the time and perhaps even push it to a larger audience.

Sources

「桃色・ピンク濫用の時代」 – 松沢呉

The Kiss and Japanese Culture after World War II – Shunsuke Kamei

カストリ雑誌 SMpedia

「昭和のあだ花 カストリ雑誌」 – 渡辺豪

More Manga Reviews

Fear Infection (Kyoufu Kansen) Manga Review – Visions of Childhood Terrors

I am always on the lookout for more extreme and challenging horror manga as a fan of work that pushes those boundaries of what is acceptable as entertainment. That said,…

Junji Ito Lovesickness Manga Collection Review

Junji Ito’s at it again with the suicide-filled creepfest that is the Lovesickness collection, and like all of his work, it is worthy of a manga review. Taking its name…

Manga Review: My Dearest Self With Malice Aforethought Vol. 1 – A Deliciously Dark Psychological Head Trip

This past year, I have come to grow a deep appreciation of digitally distributed manga. Certainly the appeal of owning a physical book will never be beat, but the digital…

Pygmalion (2015) Manga Review – It’s All Greek To Me

Pygmalion is a gory horror manga consisting of three volumes released in 2015 and concluding in 2017, written and illustrated by Chihiro Watanabe. Watanabe is known as the creator of…

God’s Child Manga Review – Nishioka Kyoudai Create a Serial Killer

True crime has become a popular sub-genre that has reached a wide audience of those looking for shock or to better understand the lowest depths of humanity. However, the genre…

Super-Dimensional Love Gun (2017) Manga Review – The Master of Modern-Day Ero-Guro

Super-Dimensional Love Gun is a 2017 ero-guro horror manga, written and illustrated by world-renowned mangaka Shintaro Kago. The manga collection of 15 short tales based around the mangaka’s distinct style…

Hi, I have a borderline obsession with Japanese showa-era culture with much of my free time spent either consuming or researching said culture. Apparently I’m now writing about it as well to share all the useless knowledge I have acquired after countless hours surfing the web and peeling through books and magazines.