“Czech Karel Kopfrkingl enjoys his job at a crematorium in the late 1930s. He likes reading the Tibetan book of the dead, and espouses the view that cremation relieves earthly suffering. At a reception, he meets Reineke, with whom he fought for Austria in the first World War. Reineke convinces Kopfrkingl to emphasize his supposedly German heritage, including sending his timid son to the German school. Reineke then suggests that Kopfrkingl’s half-Jewish wife is holding back his advancement in his job.”

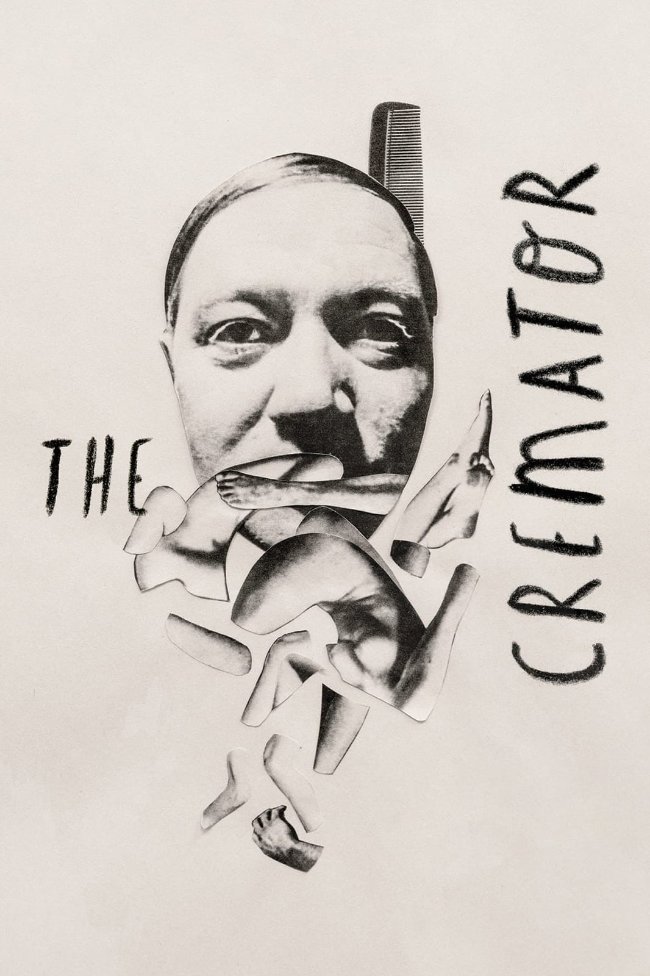

The Cremator is a sinister, immensely vulgar black comedy that plunges us into the desolate realm of a conceited, compulsive undertaker with a foolish penchant for the supposed liberation brought by premature death. A masterstroke on details, daunting evocations, and inventive chills, it surpasses generic horror film tropes.

Juraj Herz creates an overly morbid character study by filling every frame with eerie elements and terrifying musical scores that expound the wickedness of the atmosphere. From the beginning, we are fed viscerally unsettling close up images of the family and the incarcerated leopard, to the absurd animated credit sequence that graphically implies the macabre that we are about to witness. The expressionistic photography adds a sophisticated grit through the use of black and white and warped shots choices.

Rudolf Hrušínský’s powerful physical presence is a tour de force that infuses every scene with subtle yet reverberating trepidation. He captures the lofty and condescending demeanor of the cremator. Just like the portrayals of sociopathic murderers in films, he never flinches from his macabre acts nor stutters from his disturbing monologues. However, unlike the trope, he seamlessly delivers these exploits with a straight face, a feat that never requires murderous gaze or menacing laugh. Even at times of utter defeat, he still maintains a steadfast demeanor. He asserts his noble status by recapping quips from what he hears and reads, thoroughly owning different personas to adapt in different crowds of people he immerses into.

The well-placed shots highlight Hrušínský’s character Karl Kopfrking’s naturally terrorizing gaze that surpasses the known, immortalized iterations of the psychologically impaired by Jack Nicholson in The Shining, Christian Bale in American Psycho, and Anthony Hopkins from the Silence of the Lambs. Hrušínský’s prowess, which breathed life and vivacity to the character, is truly ahead of its time. His character is horrifyingly adept at convincing people of his morbid ideologies. He is the epitome of a vile politician or a pretentious, proud bourgeoisie.

The director furthers our downward odyssey of the cremator’s quirks and impulses in the amusement park. While his family finds amusement rides fascinating, he finds normal recreations tedious. He vilifies these thrills of life with his condemning gazes and deadpan guise. However, what he found enthralling is the claustrophobic chamber of horrors. While these atrocities made from wax are too sickly for most of the spectators, to him they bequeath affinity and alleviation as if for him the world of the dead is just as scenic, or much more vigorous than the effervescent terrain of the living.

His frequent physical contact warrants control rather than comfort, ascertaining his egomaniacal demeanor to control people. While we get angsty by his eerie touches, the people he touches are so swayed by his dynamism that his strokes become caresses of easement and counsel. He also touches the corpses with apparent ease and without the slightest sophistication that these dead bodies are too familiar to him. He establishes and re-establishes his supposed acumen on death by conversing about them and habitually touching them.

He found his place among the titans when he was encouraged to join the Reich. His vain belief in the transcendental merit of ill-timed death uncannily amounts to the German’s disturbing justification of antisemitism and extermination. The presence of the Germans served as a catalyst to his burgeoning descent to madness. Just as he proclaims liberation is brought by premature death, his murders seem to liberate him from his last piece of sanity.

He is a plethora of hypocrisy. While his self-absorbed and repetitious soliloquies reflect his respected reputation as an existential philosopher, he is barely a vainglorious lunatic, seeking reason for his inhumane delight on the perished. He lionizes women, but he gets easily swayed when Germans lambast women’s mere existence. He esteems a healthy and pure familial love, but he frequently fancies women in brothels and is imbibed by the thought of women. He incessantly declares his intolerance to vices and alcohol, but he is reeking of narcissism and intoxicated by his obsession for power.

The final chase scene is one of the most chilling sequences to ever grace horror cinema. His true nature finally reared its ugly head when his staggering egomania outdoes his “supposed” ultimate duty to liberate his daughter through his murders. He was once a focused and determined mien, but his gluttonous self-love stripped this away from him.

More Film Reviews:

We’re All Going to the World’s Fair (2021) Film Review – Getting Lost Online

A lonely and awkward teen joins a viral internet fad called The World’s Fair Challenge, said to potentially change you mentally and physically. After taking the challenge she begins to…

Hounded (2022) Film Review – Release the Hounds!

Having come from lower class and immigrant families, four friends make one last heist led by their leader, Chaz (Malachi Pullar-Latchman) to walk away with a small fortune to start…

It (2017) Film Review – Reboot of a Stephen King Classic

The film It (2017) surprised me. In fact, I saw it five times due to how much I enjoyed it! Unlike a majority of modern horror films, it focused more…

Suicide Forest Village (2021) Film Review – Shimizu Has Such Sights to Show You

I distinctly remember when it was announced that Takashi Shimizu, one of the most consistent contributors to Japanese horror over the last two decades, was going to direct a film…

Devil Story (1986) Film Review – What a Lovable Lump of a Man

Resurfaced from the depths of the 80’s, Devil Story is an idyllic pick for 2021 Fantastic Fest, courtesy of the good folks at Vinegar Syndrome. A showcase of inept filmmaking,…

Dead Sushi (2012) Film Review – Sushi (S)Platter

Dead Sushi is a 2012 Japanese splatter horror comedy film, written and directed by Noboru Iguchi, with additional writing from Makiko Iguchi and Jun Tsugita. Known for his over-the-top implementation…

I am a 4th year Journalism student from the Polytechnic University of the Philipines and an aspiring Filmmaker. I fancy found footage, home invasions, and gore films. Randomly unearthing good films is my third favorite thing in life. The second and first are suspending disbelief and dozing off.