The found-footage subgenre of horror is probably the most threadbare of its kind. The cinematic possibilities and the amount of legroom where a creative might pull a stunt out of it are unquestionably finite. That is because the “found footage” conceit itself is the “stunt” that is supposed to manifest only once in a while to preserve its inventiveness and shock value. After the success of The Blair Witch Project (1999), horror filmmakers found their niche in the handheld, shaky technique of shooting films to echo and reproduce the claustrophobic and realistic horror triumphantly developed by Eduardo Sánchez and Daniel Myrick. It also paved the way for a plethora of low-budget horror films to prevail. The acceptance of found footage as a genre category justifies and, somehow, sanctions the amateurish style of shooting as a feature rather than a nuisance. That’s why most of the found footage films are ill-fated, as you can only do so much with a handheld camera.

Why the lengthy introduction? Because behind this ill-fate, there are exceptions that have proven that the genre is actually a window for creativity than a dead end. Savageland is that exception. The glut of films in the subgenre allowed creatives to think about putting their own flavor in the overused trope, like using online video conferences in the Unfriended series, or the idea of splicing lost and found tapes to create a coherent film like the Graveyard Encounters (2011), or the famous mockumentary style like the Incident at Lochness (2004) and Butterfly Kisses (2018). Also, an exception is the anthology series V/H/S (2021, which employed the notion of finding tapes with different contents rather than a coherent story like the usual. Savageland, on the other hand, unearthed its story on found photos.

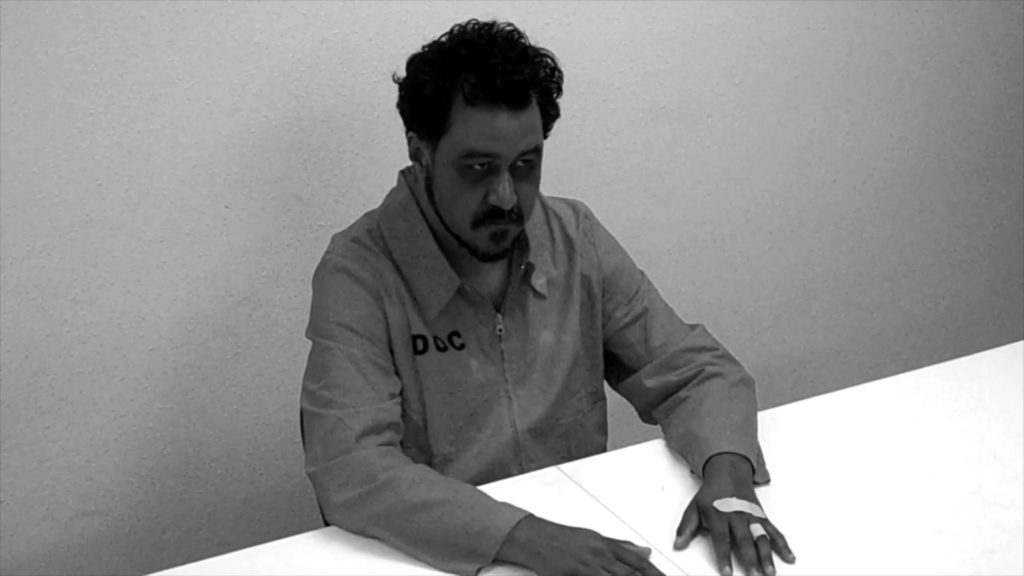

An unusual tweaking of the usually unstable camera filming, Savageland, written and directed by Phil Guidry, Simon Herbert, and David Whelan, uses a recovered camera film to uncover the truth behind the wiping out of a small border town on the Arizona-Mexico border in 2011. The discovery is narrated through a mockumentary about the trial of an immigrant, who happens to be the sole survivor behind the carnage. Having no other witnesses to testify for him, and the brimming shreds of evidence pointing towards him, the immigrant is sentenced to death. But this only scratches the surface as the photos prove the forensics and the whole state wrong. From the get-go, the issue of power structure is a highlight, as the entire trial is based on a prejudice against immigrants. Moreover, the trial by the public is painful to watch, as the shell-shocked individual does not have a chance to defend himself, as the incident still overwhelms him.

The mockumentary is as entertaining as it is harrowing because, as far as mystery and true crime documentaries go, Savageland possesses the same amount of coherent storytelling to express the traumatizing angst of the crime to the audience. The interviews with the bereaved are as real as it gets. Mapping out the whole territory also feels like the kind of sleuthing used to narrate the incidents efficiently in true crime documentaries. But the feature that creates the sense of authenticity of it all is the presence of a legitimate author, Lawrence Ross.

So, it becomes an investigation beyond the carnage and the unearthed photos, as the documentary thoroughly examines the political issues behind the systemic aggression against immigrants and people of color. But this social commentary does not feel coerced or suddenly shoved in our faces because of the narrative seamlessly attached to this commentary through the juxtaposing reflections from the citizens and the observations of an author of historical texts. It is not only a mockumentary based on the “found media”, but an all-encompassing documentary that delves further with shrewdness and social consciousness.

The photos, which is the distinctive feature of the film, are extremely nerve-racking. Found footage films would often use a turning point that would justify a character’s decision to “film everything”. More often, it is accompanied by the main character’s insistence to not put the camera down because one, the world should know what is happening, or two, it will benefit the main character’s ego that they are the ones who encountered the recorded atrocity. Either way, “persistent” filming in found footage flicks has always been impossible to believe, especially in dire situations.

However, using photos is definitely an ingenious approach to deconstruct the customarily lengthened filming using handheld cameras in the subgenre. What makes the photos much more effective is that we are saved from seeing the abomination of jittery handheld camera footage. The photographs here provide a much more horrifying account of the event than other films in the subgenre and that is because photos are no-nonsense records. We are not plunged in a hide and seek chase or a Where’s Waldo? scenario.

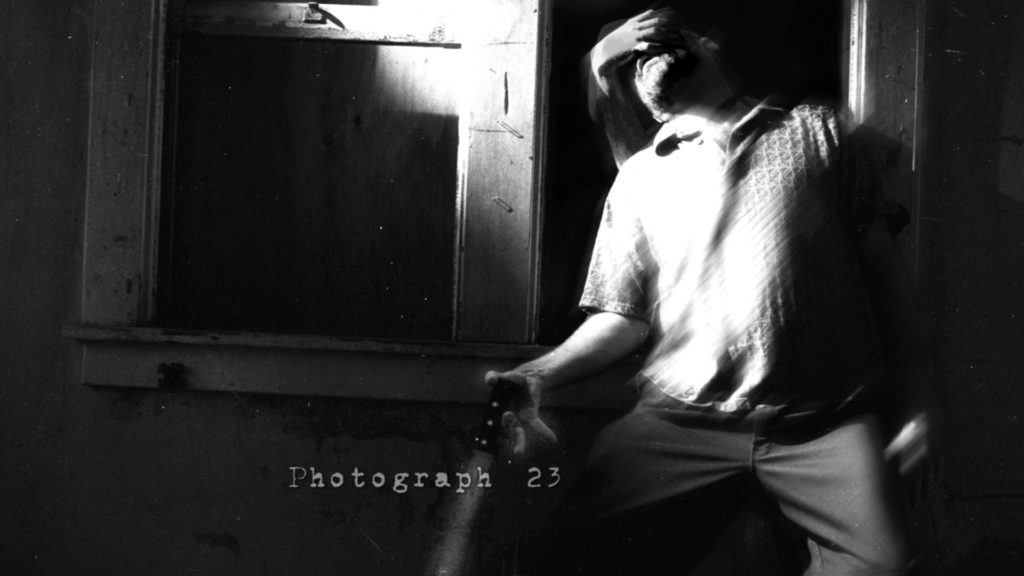

Aside from its effectiveness as a substitute to panicky home videos, the photos themselves are truly macabre. They are shot in the night in black-in-white orientation, hence the dread of twilight and desolation compressed in a four-cornered print. There are 36 photos discovered, and every single one of them is its own nightmare. But all of them lead to one thing: hopelessness. Each of them thoroughly discloses the desperation and downcast end of the citizens, and we find ourselves discouraged by the fact that their filmed frenzied states and our inability to help them will always haunt us in our imaginations.

From the photos to the narrative to the actors, the film should have run a perfect course. But some observations nearly killed its quality. One problem might be Francisco Salazar’s profiling. While it is apparent that the documentary focuses more on the photographs, I feel like his character could use a little bit more elaboration, like how his death made him more of an icon for immigrants and people of color because the end credits are a bit lacking. Another is the final moments of the film. Why do they have to deviate from their vein and go for the traditional found footage fashion? While the ending somehow coincides and ties the knot of the events photographed, it doesn’t help much in putting an end to the mockumentary. Why depend on a jumpscare when you have managed to pull a solid narrative without it? Fanning the flames, the ending appears to abolish the social discourse and goes on full horror as if washing its hands from a possible backlash with a polar opposite audience. It’s a bit disappointing, but some might find it appealing if they solely follow the incident itself and not the whole fiasco.

Found footage films have a history of repeating quirks and cheap thrills. That is why most of its features are desensitizing and, worse, expendable. However, when the last photograph flashed on the screen, Savageland instantly secured a spot in the line of indisposable found footage films. Fans and casual spotters of underrated found footage pieces will absolutely find themselves miserable, frightened, but essentially entertained.

More Film Reviews

Blood in the Snow (BITS) is a Toronto-based horror film festival that is presenting its 9th annual line-up at the Royal Alexander Theatre from November 18-23, 2021. Festival director Kelly… Jonathon Glazer’s latest directorial offering, The Zone of Interest (2023) is an understated, yet powerfully urgent warning of how easily humanity can be lost if we are allowed to lose… Jewish-themed horror movies are rare but this year’s Fantastic Fest features at least two films that explore the rich and fantastic pantheon of Jewish folklore and the role of kabbalah,… The Phoenix Lights might be one of the most intriguing pieces of UFO conspiracies on the internet. On March 13, 1997, thousands of people spotted the formation of unidentified lights… Two tragedies combine with unforeseen consequences after Amanda retreats to the country to open an B&B following the death of her husband. With her unwilling daughter Karli in tow, misfortune… Down and out, and possibly facing a midlife crisis, Georges decides he wants to change things up. The first thing on the agenda comes from a unique purchase, a deerskin…Blood in the Snow Film Festival BITS 2021- Short Films Spotlight

The Zone of Interest (2023) Film Review – A Masterful and Urgent Warning for the World

The Offering (2022) Film Review – Hasidic Horrors Haunt a Brooklyn Family

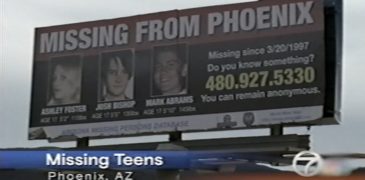

Phoenix Forgotten (2017) Film Review – Memorable or not?

The Stranger (2022) – Indie Low Budget British Horror With A Bite

Deerskin (2019) Movie Review by Quentin Dupieux – “Killer Style Never Looked so Good”

I am a 4th year Journalism student from the Polytechnic University of the Philipines and an aspiring Filmmaker. I fancy found footage, home invasions, and gore films. Randomly unearthing good films is my third favorite thing in life. The second and first are suspending disbelief and dozing off.