Co-Author Lisa Lebel

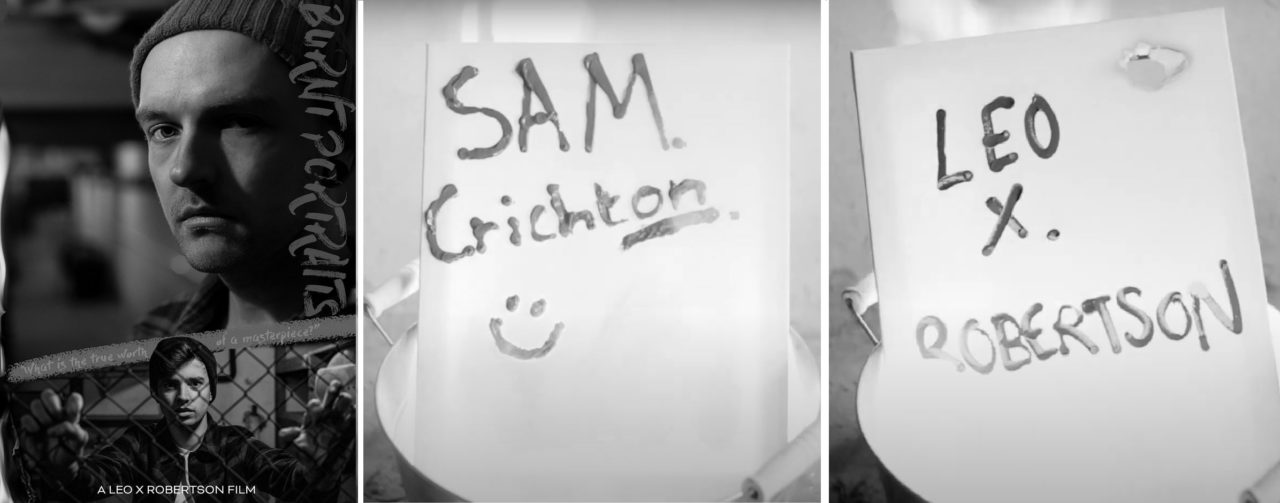

Burnt Portraits is a 2021 low-budget, single-location, psychological horror film from Leo X. Robertson. Robertson is known as being an indie filmmaker, Scottish writer and is also founder of the Stavanger Filmmakers club. Presented in black-and-white cinematography, Burnt Portraits is actually Robertson’s second feature after helming The TrutherNet Apocalypse, directing several shorts and being open in videos about why he started the filmmaking club in the first place. While this is not his first foray into horror, it is certainly his most ambitious one: the plot sees a well-known singer (Sam Crichton, also co-directing) waking up in the workshop (actually a pretty creepy-looking basement) of a painter after a night of heavy drinking. The two, both young-looking men with artistic inclinations, soon spark up an intense conversation about art, community, misanthropy and morality. The two really seem to hit it off despite their obvious differences, but the singer begins to grow worried as things his conversation partner says don’t seem to add up. Even more concerning is the growing hint of malice in his voice, the odd mannerisms and the painter’s seeming determination to shock. When the singer finally tries to leave, the movie slowly shifts into genre territory. He learns he is trapped, and juicy plot twists and more conventional storytelling replaces a crazy, rapid-fire first act that felt like one of the most intellectually stimulating conversations recently featured in any film.

The movie has a three-act structure, with every act neatly organized and essentially consisting of a beginning in which the singer deals with an unexpected situation, a dialogue-heavy middle and a twist ending. However, dialogue is the one aspect Burnt Portraits really shines at, above all else. True to a low-budget venture and to all the films it resembles, every line seems authentic and the delivery even more so. There is nothing studied, polished, or careful about the way these two men talk – it’s just like two new friends fast-talking and sometimes cutting in to say, “Man, that’s deep!”. The extreme nature of the differences between the protagonists makes the back-and-forth between the two is a delight to watch. The singer is successful, while the painter keeps a low profile, claiming to have painted thousands of portraits but burned every single one of them. The singer is also grateful for his success, whereas the painter a firm believer in chaos as a ruling force. The interaction between the two truly feels like the last stage of a debate-club championship at times. In fact, the movie almost acknowledges that for discourse to reach peak levels, the debaters must sometimes pick opposing views even when they don’t personally adhere to them, just to keep the conversation alive and maintain a sense of balance.

Really, Burnt Portraits ticks all the naturalism checkboxes from the start. Taboo subjects? Check. Dialogue-time roughly equal to real time? Check. Single location? Check. Characters who see themselves as victims of circumstance? You got it. Viewing this film feels akin to watching a theatrical performance at first, but the last two acts manage to truly emulate the feel of genre films by heavily relying on tension, misdirection and subtle cues meant to conjure up the viewer’s past experience with any thrillers. The audience will feel at home with classic horror elements, such as a dissonant chord here and there, a change in mood, even framing the painter in a more menacing light, or lack thereof. Of course, this film was never going to be just an engaging debate between two artists!

For horror fans looking for a comparison, Burnt Portraits can feel like Patrick Brice’s Creep and M. Night Shyamalan’s Split, with a bit of Daniel Isn’t Real on the side. Robertson, just like Adam Egypt Mortimer with Daniel, makes a film about a man trying to do good, with a nemesis that is designed to test his limits. Just like in Creep, there is a lot of uncomfortable comedy in the two men invading each other’s private spaces or just saying things that would have them cancelled if the public ever caught wind of them. Finally, just like in Split, there is an element of Robertson juggling multiple personas, but we won’t spoil how relevant that is to the story as a whole, or how many there are.

Portraits borrows themes from all those movies and, although it starts out more like an LGBTQ+ drama about two artists sharing a moment, the viewer is always left to question everything. What’s being said, what’s not being said, the subtle cues that all is not what it seems – for a first-time director, Robertson steers his ship through some treacherous waters and while he doesn’t exactly stick the landing, one is left with the impression that the journey is far more important than the destination. Robertson, a writer with almost a decade of experience to help him, essentially pulls off a high-wire act for most of the movie’s duration. Burnt Portraits really bets just about everything on his performance and all the ambiguity it is able to spark in a discerning viewer’s mind. Is the painter just a jaded anarchist, or a deranged maniac? Does he have ulterior motives? What if you’re just being prejudiced? (It might also remind readers of Joey Goebel’s cult novel Torture the Artist and the age-old idea that art can arise only in the bleakest of circumstances.)

The first act clearly puts the two men on different ideological sides and seems to have an ear for modern issues related to art. There is talk of religion, the ubiquity of art, and even the “immoral act of making more art”, Soundcloud bedroom-artists and Twitch streamers. Because the discussion soon switches to the dutiful destruction of art vs. the value of the art community, some viewers might at this point find the movie pretentious or just an extremely challenging, dialogue-heavy watch. (The lack of subtitles surely doesn’t do it any favors – more than with any mumblecore movie, one has to pay attention at all times, or some details will be lost.) However, some forgiving viewers will be delighted to be reminded of their own contrarian friend in the group, the loud, boisterous one who always brings color to everyday chats by simply disagreeing with everything and everyone – or even realize they were that friend in somebody’s eyes.

As the first act is revealed to have been a delicate ruse and the singer finds himself as a potential victim of a killer, unable to leave the workshop, the painter reveals that he’s also in the same position and that it’s been that way for ages, but how much of anything that he says can be taken at face value? Just as the two start talking about this murderer seemingly eyeing famous artists, the topics get darker and darker: the surveillance state, evil as a growing addiction, the Dark Web, the lost potential of murdered artists (and – oh dear – OnlyFans and a girlfriend with the moniker “Lapis Lazuli”). Fear and anxiety become the catalyst for many uncomfortable silences, which give a much necessary change in the movie’s pacing. The second act still carries on with great storytelling and a variety of themes which it deftly handles, and even some character development for the singer, who isn’t exactly a saint. However, at this point viewers might again be put off, this time by the total lack of laughs…and nonetheless be delighted to find out that this is the exact point in which the awkward, cringeworthy comedy style that made Creep a sleeper hit makes its way into the movie, especially in Robertson’s performance.

When you realize that Robertson’s painter could essentially be the same type of character that Mark Duplass played – a troll who’s in it for the art as much as he is all about the reactions – you might let out a loud “a-ha!”. The question then becomes “How much of a creep is he?” and “How uncomfortable will this movie dare to become?” And it does get pretty uncomfortable. Part of it is Robertson’s unhinged act – sure, he pulls off the crazy eyes and the mannerisms, but he’s not Ramsay Bolton-crazy. A lot, however, is because of how realistic the situation is. Both of these guys are normal-looking people you would see on the street and think they’re arguing intensely about an art project. In fact, most people who will watch Burnt Portraits will do it first and foremost because they’re fans of indie or underground cinema and will be pleased to find the elements that this genre is most well-known for, specifically the naturalistic, raw acting, the lack of any glam whatsoever, and dialogue that just “rings true.” And it so happens that the movie shines in all of those areas.

Burnt Portraits just doesn’t excel at the art of escalation, dread and terror that any horror fan expects from a good genre movie right now, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t try. Because of the three-act structure and the fact that in every act the aim is to keep the dialogue flowing, the escalation suffers – you know what the implications are at any moment, but the movie just dances around them. Some might enjoy that, while others may find it tiresome. When all bets are finally off, it’s essentially a matter of the viewers being on the same wavelength as Robertson’s multi-pronged approach.

But does the painter pull of a great villain speech, even when you’re still unsure who the villain is? He sure does. However, falling for his antics and then having the rug pulled out from under you repeatedly becomes a “Fool me once, fool me twice” affair, and the third act is definitely the weakest, being the most static of the three (the actors are literally sitting down, and the camera stays in place for most of the duration). The film grows to queasy, mind-numbing extremes, and could be summed up as “persuasion failure” – the movie’s attempt at portraying a twisted mind trying to control, to groom a more innocent one mirroring the lack of restraint of its villain. Guitar music mixed too loudly can really grate over a poetic summarizing of grief, as the dialogue broadly tackles mental illness, imposter syndrome, the ridiculous standards that famous people are held up to in today’s society, and the seductive power of celebrities. Still, the movie picks itself back up with a great breakdown scene, and an inspired montage depicts the pain an artist goes through when having to create perfection.

The strong core, the black and white cinematography, those are very well-chosen attributes as a window into a movie about division and gaslighting, and the rich exploration of themes carry the film for most of the time. However, the amount of pathos in the finale effectively smothers most of the good-will left in the wake of what, at the very least, had always amounted to a challenging, tightrope-walking act. The resolution might be smart, but the two actors can’t seem to pull it off, or even want to – the editing is hurried, as if the movie is rushing past this part, it’s showing it doesn’t much care for its conclusion. But neither should it really, when the rest of it is so strong, and so refreshing – however much an unsuccessful ending might be anathema in a horror fan’s playbook.

Listening to Robertson talk on his Youtube channel, one is left with the impression that Portraits is a much more personal affair than initially meets the eye. While this film is certainly not for everyone, it is most certainly more enjoyable for fans of Art School Confidential (which did, at times, venture into the uncanny valley) or Richard Linklater’s movies than your average horror-fare. Linklater himself has an unyielding focus on dialogue (Tape would be an apt comparison, and the man is one of the godfathers of the indie film movement), with Robertson clearly ending up an inspiration for any beginning filmmaker with his lengthy videos explaining his craft, and with his clever storytelling devices.

Overall, Burnt Portraits is a stimulating movie, a total win for low-budget cinema and even (if you disregard the awkward ending) a quality horror film. And you know what? Not even the first Creep was perfect – Brice returned with a much stronger second entry which furthered the themes and featured a much more (and we mean deeply) unsettling portrayal from his star. We have every reason to believe that Robertson could do the same with his next movie, and he is certainly one to follow for fans of independent cinema. Indie horror might have essentially saved the genre after 2012 with the ascent of VOD and the temporary fall of studio horror obsessed about remakes and sequels, and perhaps low-budget horror will leave the same mark too, if left in capable hands like Robertson’s.

More Film Reviews

Despite having seemingly insurmountable shoes to fill, Brandon Cronenberg is proving himself to become a sophisticated auter with a deranged vision. His interest in pushing the boundaries and distortions of… It was about halfway through watching Rob Jabbaz’s debut feature The Sadness that I realized I was in the hands of a maniac. Taipei resident Kat (Regina Lei) is hiding… From director Banjong Pisanthanakun and writer Na Hong-jin comes a Thai-Korean, Shudder exclusive feature exploring the thin line between humans and spirits – and what happens to those who cross… I had the great fortune of viewing the documentary Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist (2021) at this years’ Nightstream horror film festival. As a longtime fan of his work it turned out… Directors Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead blew me away with the debut film Resolution, an eerie tale marked by a foreboding sense of doom. Their follow-up film, Spring, I will admit being… Director Koji Shiraishi takes a dip into cryptozoology in Senritsu Kaiki File Kowasugi! File 03: Legend of a Human-Eating Kappa (shortened to File 03). In this third installment in the…Infinity Pool (2023) Film Review: A Psychosexual, Phantasmagorical Nightmare

The Sadness (2021) Film Review- A Powerful, Repellent Horror Spectacle

The Medium (2021) Film Review: Shudder’s Shamanistic Mockumentary Is Far From Middling

Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist (2021) Film Review: A Short Life with Immeasurable Impact

Synchronic (2020) Film Review: Everyone In The Past Wants To Stab You

Senritsu Kaiki File Kowasugi! File 03: Legend of a Human-Eating Kappa (2013) Film Review- Now it’s a cryptid!