The “Death Game” is an unofficial genre of thriller wherein a set of humans (or at least sentient beings) are pitted in a contest where the consequence of failure is the player’s last reward. The appeal isn’t hard to explain – the premise packs immediate tension as characters are faced not only with the threat of their ultimate end but with moral and philosophical challenges that appear when the very fabric of civilization reduces their lives to playthings.

May-the-worst-man-die fiction has a varied history, beginning with The Most Dangerous Game, a 1924 novella by Richard Connel. The title conceals a clever turn of phrase wherein the word “game” refers to the hunt represented in the story, as well the game being hunted: man. Coincidentally, some believe this piece influenced the real-life Zodiac killer, as one of his infamous cryptograms reveals an ominous phrase: “MAN IS THE MOST DANGEROUS ANIMAL”.

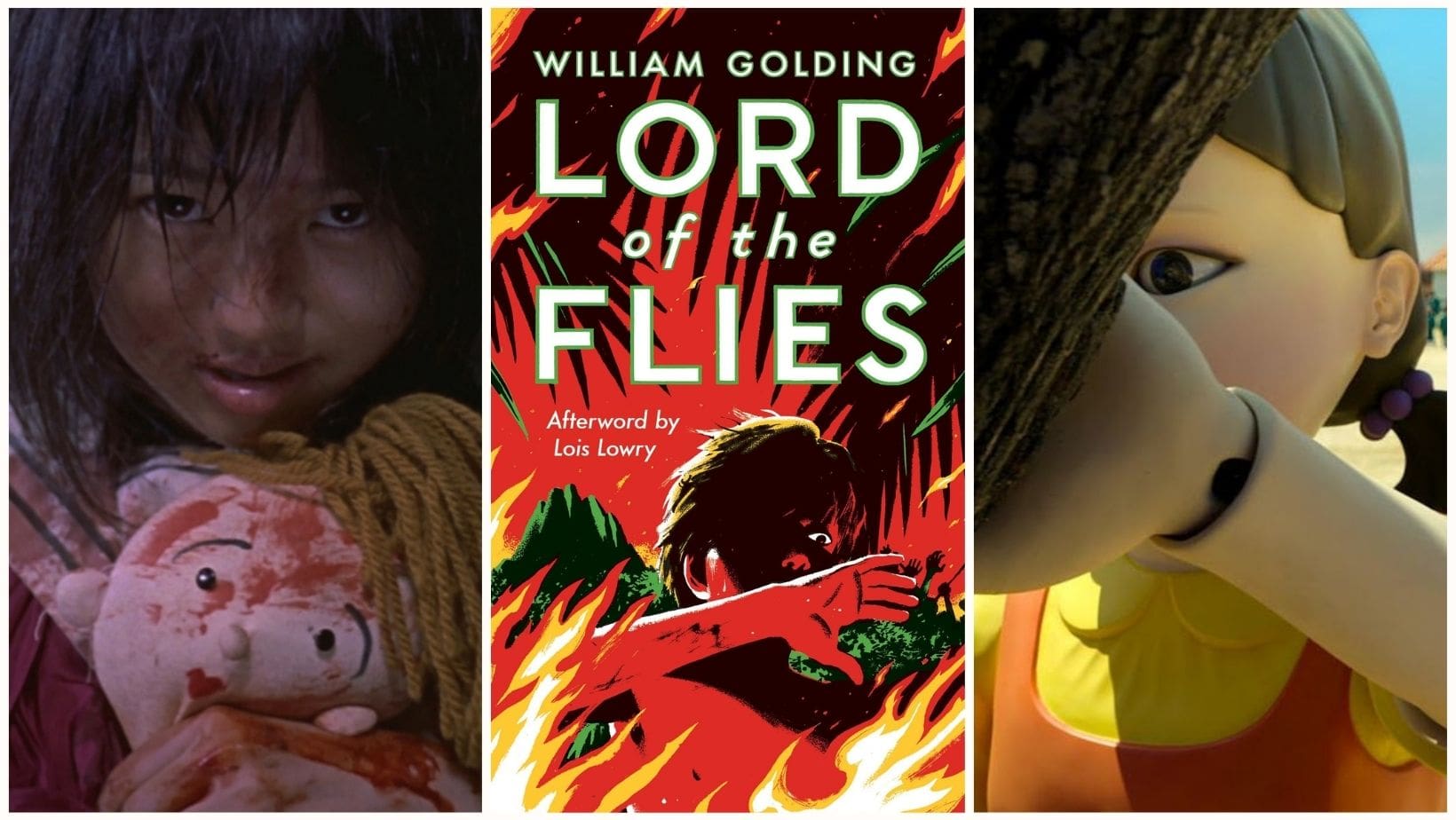

Perhaps the most influential story in the genre arrives in the form of compulsory reading – none other than Nobel laureate William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (1954). Though the classic piece of literature doesn’t involve any sort of death sport, it concerns a group of young people constrained to a hostile environment that forces them to kill or be killed. Sound familiar?

This concept of sociological implosion must have smelled good to at least one young man, who went on to write his own interpretation. I refer to none other than Stephen King himself. Directly influenced by Golding and working under the pseudonym of Richard Bachman, he wrote a short story titled The Long Walk (1979) in which a hundred boys compete in a marathon to the death. Three years down the line, “Bachman” wrote The Running Man, working off a similar idea, later adapted into an action flick starring everyone’s favorite Austrian, Arnold Schwarzenegger.

King’s books lit a fire in prospecting Japanese author Koushun Takami, who would pen the doorstopper that is Battle Royale (1999), leading to the seminal movie adaptation. The turn of the millennium was also when reality TV started kicking off in a big way, sparking the public’s imagination. The rest, as they say, is history. Now we have everything from Katniss Everdeen to Fortnite, Danganronpa, and The Saw franchise, not to neglect the most recent pop-culture offering, exploding onto the scene unlike anything before, Netflix’s Squid Game (2021).

Aside from the immediate appeal of competition under threat of ultimate punishment, there is much to be examined in death games. From game mechanics to “how-to-beat” guides, character interaction and twists on the genre. There is one odd element in particular that plenty of these stories share, however. Any guesses? I’ll give you a hint – it rhymes with “myopia”.

That’s right – a hell of a lot of these stories take place in a dystopic version of the world lorded over by an oppressive government. In The Hunger Games, it’s The Capitol. In Battle Royale – the fascist Republic of Greater East Asia. In The Long Walk, it’s The Military and in Squid Game, it’s billionaires

In other words, these stories show the resultant forces of a corrupt society coming together to shape a perverted form of entertainment where the injustice present in that world is amplified to the extreme. If society is a disease, the death game is its symptom. We best demonstrate this by looking at how the contestants forced to take part in the games are always that fictional world’s version of the unprivileged. The Long Walk, for instance, takes place in an “ultra-conservative” future that venerates its military. How fitting that the ones whose lives are taken away be young boys; the casualties of the army.

Because as accustomed as we are to fictionalized death games, it’s easy to forget they exist in real life. From the very real Russian roulette to the constant presence of the “honorable” duel throughout history. To encounter a version with the amount of glamour and scale exhibited in modern fiction, however, we might take a trip to Ancient Rome. As many as eighty thousand spectators, from the lowly poor to the obscenely affluent, would gather in the Colosseum and other amphitheaters around the empire to witness gladiatorial bloodsport, cheer for their favorite contestants, or witness them getting mauled.

We might decry the Romans as barbaric for their enjoyment of brutal arena combat. But could we diagnose this aspect of Roman culture as the symptom of an absurdly unequal society of Caesars and war slaves, unbridled imperialism, and the cheapness of human life?

In this, we draw a one-by-one comparison with the world of The Hunger Games (2008). After the Capitol took over the world, it subjugated its people into 12 Districts. To affirm dominance, they host an annual competition where two slaves from each District are taken to a remote, enclosed location to kill and be killed until a single soul remains. Residents of the dominant Capitol serve the allegory of the Romans watching the games as entertainment. To strengthen the connection between societal ills and blood sport, we examine the subsequent installments of the series, Catching Fire and Mockingjay. As we progress, the focus narrows more and more on the injustice and cruelty wreaked by the decadent Capitol until the story reaches a point of total rebellion. The pop-culture legacy of The Hunger Games is its portrayal of a young-adult revolution against a corrupt empire, more so than the initial death game premise.

Squid Game shows us a particularly topical rendition. The corrupt society that spawns a terrifying series of children’s games with deadly consequences isn’t some far-flung dystopia, but our very own, current capitalistic world. In an intensely neoliberal society, the impoverished are an undesirable class, subjugated by the necessity of money, and trapped by its insufficiency.

After the initial group drafted into the Squid Game suffers its first game, as well as its first mass casualty, the contestants are given the choice to leave and ply forward on their own in the cold, harsh world. Not only do nearly half the contestants vote to stay, almost all of them decide to return after being initially dismissed. In a subversion of the confinement trope, the real horror doesn’t lurk in the claustrophobic entrapment, but the economic reality these characters face.

The manifestation of this ill will into a societal ulcer that is the game of death might seem like fictionalized absurdity until we once again remember the historic duel. What tangible thing is this “honor” that pushes two individuals to commit to a standardized bout, ending when one of them lies flat?

A hidden ingredient present in these stories typifies them as much as the surface-level idea of death sport. Like dystopian novels, they are warnings, or concerns, that a tainted element of the human world might rot it to the ground. The real threat is civilization not functioning as intended.

More Reviews

Tammy lives a regular teenage life, with an overbearing bible-thumping mother-in-law who hates filth and a father who would do anything for her daughter, whether it be beheading a donkey… Ever since I was a small child, I have had a fascination with monster movies. They bring back nostalgic memories of sitting for hours on end, watching black and white… The film It (2017) surprised me. In fact, I saw it five times due to how much I enjoyed it! Unlike a majority of modern horror films, it focused more… The horror genre has been flooded with a ton of films and sometimes certain gems can slip through the cracks, and go unseen for a long time. Enter “Dead Snow”…. From director Banjong Pisanthanakun and writer Na Hong-jin comes a Thai-Korean, Shudder exclusive feature exploring the thin line between humans and spirits – and what happens to those who cross… Pussycake (Emesis) is a 2021 Argentinian sci-fi horror, written and directed by Pablo Parés, with additional writing from Maxi Ferzzola and Hernán Moyano. Pablo is no stranger in the directorial chair, having over thirty-six productions under his…Blonde Death (1984) Film Review – Zed Grade John Waters [Fantastic Fest]

Spookies (1985) Film Review: These Spooks Were Made for Walkin’

It (2017) Film Review – Reboot of a Stephen King Classic

DEAD SNOW Review (2009) – An Entertaining Bloodbath!

The Medium (2021) Film Review: Shudder’s Shamanistic Mockumentary Is Far From Middling

Pussycake (2021) Film Review – Curiosity Killed the Pussycake

![Blonde Death (1984) Film Review – Zed Grade John Waters [Fantastic Fest]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/blonde-death-film-review-365x180.jpg)