Despite being one of Japan’s biggest film studios throughout the late 40s and 50s during the golden age of Japanese cinema, Daiei were struggling by the mid-60s and had to slash budgets for their productions. This eventually led to a merger with Nikkatsu in 1970, followed by bankruptcy in 1971. Somewhat overlooked is Daiei’s 1968-1969 period where they started to focus on exploitation films and could be considered as their own equivalent to “pinky violence“. This era of exploitation, dubbed by Daiei as their “ero guro/unique historical drama” line, is largely defined by two film series: the Woman’s Secret series and the Kanto Woman series. The Woman’s Secret series kicked off this new line with a focus on historical-set exploitation films, the first being Secrets of a Woman’s Prison in 1968. The second film in the series, Secrets of a House of Women focuses on the infamous Yoshiwara red-light district.

Because of how obscure this film is, Rob has outlined the plot below. If you want to avoid spoilers, skip down to the “Spoilers end here” tag below.

After the untimely death of her father, a young woman, Onatsu (Michiyo Yasuda) inherits his debts. Unable to pay them off herself, she voluntarily sells herself to a Yoshiwara brothel under the care of a young man named Naojiro (Masakazu Tamura) who works as a scout for new girls. Once accepted into the brothel, she is mentored on the customs by a woman called Kane who acts as a servant and housekeeper. Onatsu learns of the complex hierarchy and rules of the brothel which exists as its own closed-off community. Much to Onatsu’s shock she also learns of the punishment for breaking said customs and Kane gleefully shows off the brothel’s punishment chamber where a prostitute is strung up from the rafters and beaten with bamboo sticks.

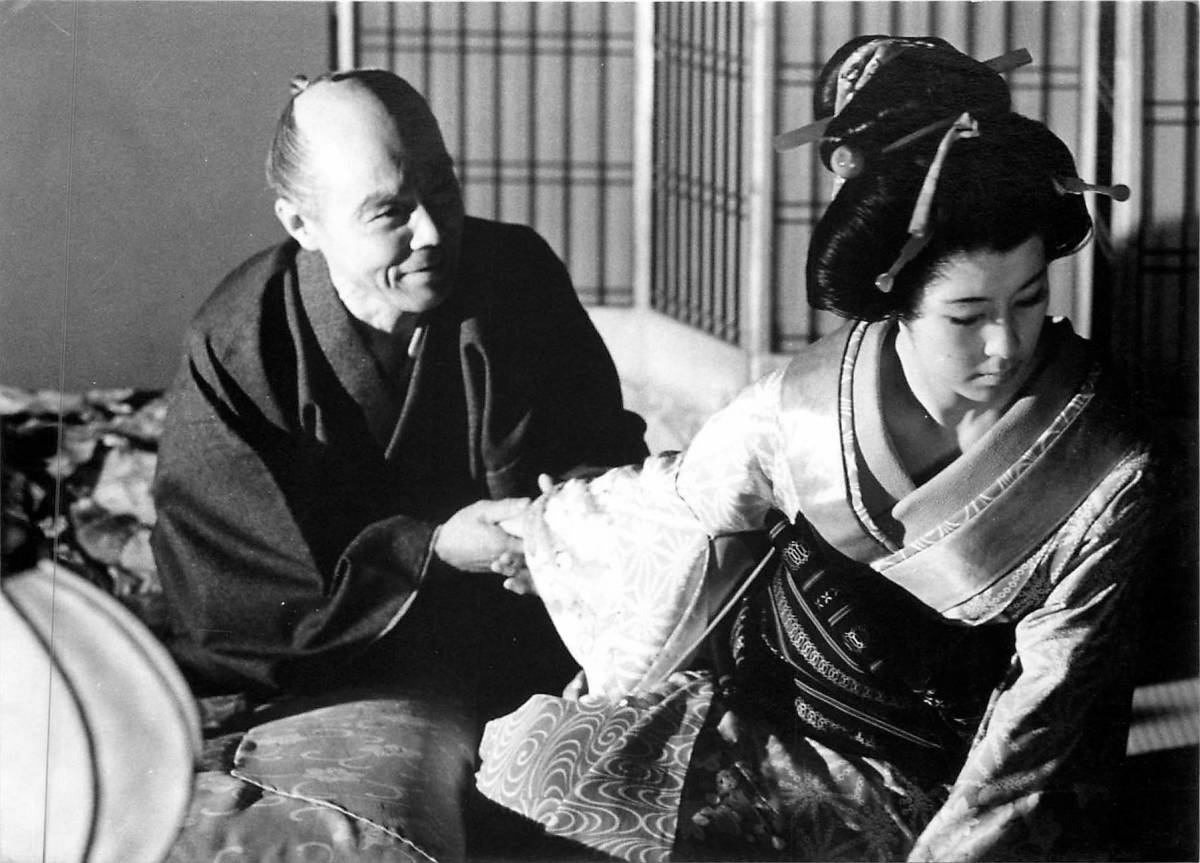

After her lengthy induction, Onatsu finally takes on her first client: an elderly man named Negishi. (According to the rules of Yoshiwara a client must first visit his chosen prostitute on three separate occasions before he is permitted to sleep with her.) Accompanying him on the trip is Minokichi, one of her father’s servants who had initially tried to force himself on Onatsu following her father’s funeral. He is surprised that Onatsu is working there and mocks her out of jealousy and resentment.

A few days later, Onatsu overhears a conversation in which she discovers that Negishi is actually a man called Ryogokuya: a ruthless businessman who drove her father to his death. Not knowing Onatsu’s identity, Ryogokuya unwisely leaves some documents in her chamber when he is called away on business; among these documents is an incriminating letter which outlines Ryogokuya’s corruption and crimes. Onatsu attempts to sneak out of the fortress-like brothel to seek revenge but is quickly caught by Naojiro who takes the document from her and advises her against taking a rash decision.

She is escorted back to the brothel where Naojiro sneaks her back in, but Kane notices this and quickly bundles Onatsu into the punishment chamber. In the meantime, Naojiro uses the information outlined in the letter to blackmail Minokichi for his role in Onatsu’s father’s death. Ryogokuya later realises that Onatsu is responsible for stealing the letter and heavily beats her, all with Kane’s sadistic blessing. Minokichi gathers some thugs to attack Naojiro and they end up stabbing each other to death in the ensuing fight. When a constable is alerted to the altercation, he finds the incriminating letter on Naojiro’s body and travels to the brothel to arrest Ryogokuya. Despite being rescued from her torturers, Onatsu’s situation hasn’t changed and the final shots show her still working at the brothel, ever imprisoned by her debts.

End of Spoilers

Each film in the Woman’s Secret series begins the same way with a narration explaining the historical setting of the film, putting on airs of documentary presentation belying the exploitation that will come later. Secrets of a House of Women goes to great lengths in showing the setting of Yoshiwara, going so far as to even show a historical map of the area onscreen. Yoshiwara was a sprawling and notorious red-light district in Tokyo (known at the time as Edo) which at its height housed 3,000 women. With its closed-off nature from regular society, Yoshiwara developed its own culture and customs unique to the district; it is these customs that form much of the basis of the film’s background. In doing so, Secrets of a House of Women is one of the only films to portray the unique custom of “fumiai” or “stomping”: this occurs when the madam of one brothel accuses another of stealing her patrons, and results in a one-on-one fight for dominance. Despite the low budget of the Woman’s Secret series, the production department was seemingly spared no expense when it came to costuming and the sumptuous clothing and jewellery of the prostitutes provides a stark contrast to the penniless reality of the women forced to work at the luxurious brothel – in particular, the brothel madam appears practically regal and is treated much like royalty.

Unfortunately, outside of this unique setting, the film has very little to say and is oddly bereft of any sex or commentary on prostitution in general, and certainly doesn’t deliver the bondage scenes promised so prominently on the poster. Admittedly, for a film based purely around a brothel, it is quite refreshing to avoid the overt exploitation that usually accompanies such a subject matter. In many ways it is very similar to the later Secrets of a Woman’s Temple, however, Secrets of a House of Women never properly explores its protagonist and her experience with anywhere near the same levels of depth. Despite the overall lack of explicitness, director Kazuo Mori nevertheless achieves an effortlessly sleazy atmosphere in and around the brothel. Interior scenes receive minimal lighting via candlelight where the light of the flames laps against the walls almost sensually, invoking an oppressive yet sordid ambience. Hopelessness is the emotion which undercuts the film’s overall tone, constantly weighing heavier throughout to near-overwhelming levels for the character of Onatsu. Writer Shozaburo Asai commits to this feeling totally and bravely denies Onatsu any true semblance of happiness and resolution, choosing to close with a bleak epilogue which was no doubt representative of the many real-life prostitutes that the film portrays.

The role of Onatsu plays to Michiyo Yasuda’s usual strengths, who balances her character’s doe-like naivety with the fortitude needed to survive in this new dangerous world. Like the protagonist in Secrets of a Woman’s Temple, Onatsu is reluctantly housed in an oppressive and abusive institution. Initially, we see her shock at life in the brothel – from the sadistic punishment to the general business of prostitution. An especially evocative scene shows a long line of impeccably dressed and decorated prostitutes sitting behind a barred screen at the roadside like cattle at the market, ready for a patron to pick out. However, when it finally comes to Onatsu’s first experience with a customer, the audience is never truly shown her feelings or anxiety prior. With her first time interrupted by the suicide of another prostitute, Onatsu never actually has to sleep with a patron at any point in the film which greatly reduces the portrayal of suffering that the film so firmly relies on.

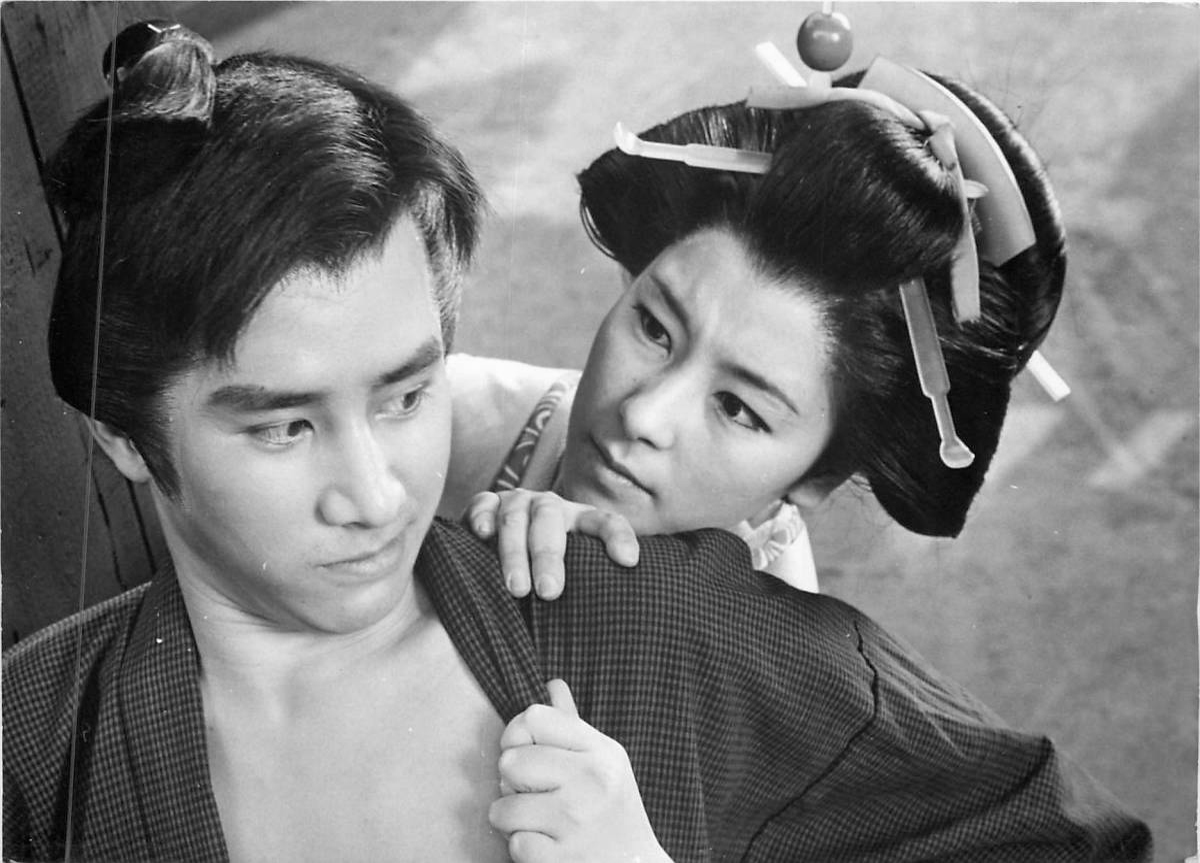

Other than Onatsu, one of the most interesting characters in the film is Naojiro. The man is a complicated study of morality: on the one hand, he is the only person who has Onatsu’s best interests at heart and defends her against the criticism of Minokichi; on the other, he seems to have little to no qualms at selling desperate young women to the brothel, of which he takes his own cut of the payment. Conversely, one could argue the women being sold to the brothel are having to do so out of sheer desperation and Naojiro offers them and their families the only chance to secure that kind of money. The film balances this moral quandary well, and by involving Naojiro with the larger plot surrounding Ryogokuya and the death of Onatsu’s father, he is offered an important chance of redemption and the ability to show his honour compared to the true villains of the film. Masakazu Tamura offers an impressive performance portraying Naojima’s underlying guilt and enables the audience to warm to his character despite his transgressions.

Overall, with its Yoshiwara setting, Secrets of a House of Women is best enjoyed for its unparalleled look into the culture and life inside these historical brothels. However, in search of conflict, the film sacrifices opportunities to portray the life and emotions of the characters forced to live and work in the brothel. Despite a strong first act, the film eventually ends up feeling too unfocused as it progresses and seemingly loses interest in the plot of a young woman struggling with brothel life in favour of a story of betrayal between men. With the main plot solved by a borderline Deus-ex-Machina, the film ends up feeling empty and even Onatsu’s emotional epilogue rings hollow.

More Film Reviews

The Show (1927) Film Review- A Fun Silent Carnival Ride

Tod Browning is best known for directing creepy, silent films such as Freaks and Dracula, but before he made movies, he was a circus performer and carnival sideshow host. Perhaps…

Brooklyn 45 (2023) Film Review – War is Hell

Is there such a thing as a good war? After World War I, the Allies left Germany in a state of defeat and despair. Consequently, one man used the disheartened…

The Sadness Film Review – What The F*** Did I Just Watch!?

The Sadness has been a film making some early commotion due to an extreme and graphic nature – a new angle on the zombie genre in the age of our…

DEAD SNOW Review (2009) – An Entertaining Bloodbath!

The horror genre has been flooded with a ton of films and sometimes certain gems can slip through the cracks, and go unseen for a long time. Enter “Dead Snow”….

Savageland (2015) Film Review – The Camera Doesn’t Lie

The found-footage subgenre of horror is probably the most threadbare of its kind. The cinematic possibilities and the amount of legroom where a creative might pull a stunt out of…

Poser (2021) Film Review – The Art of Fitting In

Finding a sense of belonging is built into the core of human existence. In Poser 2021, the debut feature from filmmakers Noah Dixon and Ori Segev, we delve deep into…

Hi, I have a borderline obsession with Japanese showa-era culture with much of my free time spent either consuming or researching said culture. Apparently I’m now writing about it as well to share all the useless knowledge I have acquired after countless hours surfing the web and peeling through books and magazines.