Despite being one of Japan’s biggest film studios throughout the late 40s and 50s during the golden age of Japanese cinema, Daiei were struggling by the mid-60s and had to slash budgets for their productions. This eventually led to a merger with Nikkatsu in 1970, followed by bankruptcy in 1971. Somewhat overlooked is Daiei’s 1968-1969 period where they started to focus on exploitation films and could be considered as their own equivalent to “pinky violence“. This era of exploitation, dubbed by Daiei as their “ero guro/unique historical drama” line, was largely defined by two film series: the Women’s Secret series and the Kanto Woman series. The Kanto Woman series began in August 1968 and consisted of four thematically-linked standalone films.

Because of how obscure this film is, Rob has outlined the plot below. If you want to avoid spoilers, skip down to the “Spoilers end here” tag below.

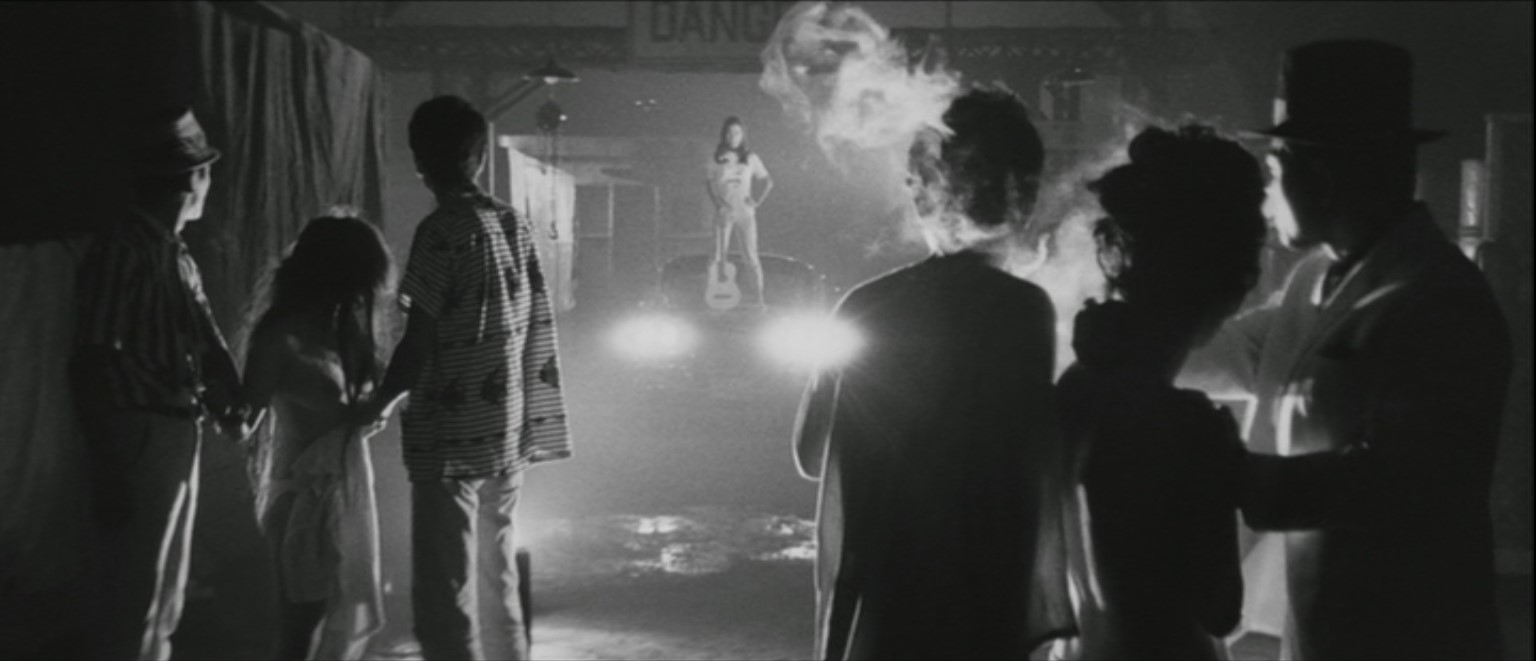

The film opens with shots of a Kansai port town at night. Thick fog sits above the ground and dim streetlights break through the gloom in the hustle and bustle of urban nightlife. A jazz blues soundtrack accompanies the visuals with a sleazy, yet somber saxophone crooning through the darkness. Along the industrial backroads, a trio of female musicians walk: Minako (Michiyo Yasuda), Tamaki (Mayumi Nagisa), and Yoshie (Mako Sanjo). They have traveled all the way from Kanto in search of Minako’s brother, Chuichi, who has seemingly gone missing. In the distance, a pair of headlights from a car cut through the night. As the car comes closer the doors suddenly swing open and its occupants, a small group of yakuza thugs, manage to bundle Tamaki and Yoshie into the car before driving off with a flurry of torn clothes flying out of the windows as they strip the girls. When they pull over to attempt to r*pe them, Minako appears and defiantly jumps on the bonnet of their car. When the men try to attack her, she shows that she is a force to be reckoned with as, with the twist of a tuning peg, a retractable blade appears from the base of her guitar and she manages to fight off the assailants, slashing and stabbing them to great effect.

After learning that the thugs belong to the local Hatanaka yakuza clan, she sets up a meeting with their boss to propose a truce. She is challenged to a game of dice: if she wins, she gets to carry on the search for her brother without any more hassle, but if he wins the girls must work at one of his bars. Minako’s deft manipulation of the dice secures her a victory, although it’s not long until she learns how little the Hatanaka boss’s word means. After performing at a club the next night, Tamaki is set upon in an alleyway once again by the group of thugs who drag her to a phone booth and attempt to r*pe her. This time Minako is on the backfoot but fortunately a man, Amano (played by Toshiyuki Hosokawa), is walking past and is able to help her fight off the thugs.

Soon, Minako begins a friendship with Amano and the girls steadily settle into town life as their search continues—Minako even starts dating. When Minako’s new boyfriend is out helping her investigate her brother’s whereabouts, he is run down by the thugs in their car. After he is hit, a stranger helps him to the hospital and when Minako goes to thank the stranger, she discovers that he is none other than Chuichi. Reunited with her brother, Minako learns of the reason for his disappearance: he was once loyal to the Hatanaka clan, and during a turf war with the rival Hanafusa clan, he stabbed one of their members and was arrested. Even after serving his time in jail, he is far from free and has been forced to live as a fugitive as various members of the Hanafusa clan are hunting him down to take revenge. Minako tries to ask Amano to help her brother and his wife but he surprises her by coldly denying any assistance.

Things come to a head when Tamaki is lured to an apartment with the Hatanaka boss waiting to force himself upon her. The morning after her ordeal she overhears him talking to one of his underbosses who is accompanied by a Hanafusa hitman who is hunting down Chuichi, the hitman being none other than Amano. After Minako is told of this by Tamaki, her initial plan is to buy ferry tickets for her brother and his wife to get them out of town, but it is all too little too late. With his fate sealed, Chuichi agrees to a 5 AM showdown with Amano at the quayside. As a final attempt to save her brother, Minako sets the clocks back 30 minutes and attends the meeting herself, disguised in the dense mist as her brother.

***Spoilers end here!***

At first glance, it would be easy to mistake the film for a sukeban flick. In fact, Daiei leaned heavily into this aspect when promoting the film, focusing almost entirely on scenes of the girls fighting for use on their promotional sheets and photos. It is not until the opening is concluded that the film truly opens itself up to the viewer and is revealed to be a moody and spectacularly realised neo-noir. Both director Akira Inoue and cinematographer Chishi Makiura (of Lone Wolf and Cub fame) utilise every tool in their extensive box to craft a stylish and endlessly atmospheric film. Great care is taken to elevate every single shot to its artistic peak, no matter how mundane. Every inch of the screen is taken advantage of, with each creative and truly unique shot perfectly framed and formulated in order to capture the maximum amount of unspoken subtext and mood from each scene. That being said, with an almost endless abundance of these shots, they do eventually verge on the excessive and, despite their beauty, begin to hinder the viewer’s immersion.

Akira Inoue is keen to highlight the character of the town itself, which is excellently explored and portrayed with its dilapidation and stagnation shown in every shot: torn posters flapping in the wind, rubbish-strewn backstreets, and of course the thick fog which enshrouds everything in a polluted and muggy blanket. The sun never shines in this town, nor do the stars twinkle; the nights are lit only by the glow of artificial streetlights and passing cars, whilst the days are characterised by a constant, ever-grey sky. Chishi Makiura takes full advantage of the black and white presentation, lighting each scene impeccably to convey the utter dreariness felt literally and metaphorically. Despite the consuming maw of darkness, the overall visibility is never sacrificed.

One of the most effective and unique features of the film is its achievement of a dynamic tone and mood. At the start, much like the girls themselves, the tone is rather carefree and excitable. However, as events play out, the mood slowly sours as the depressing reality of the city dawns on our characters. The melancholy absorbs everything in its wake and, much like the constant fog present, eventually seeps into every aspect of the film including the direction and cinematography. The early scenes in the film are characterised by fun, quick cuts perfectly exaggerating the cocky attitude of its protagonists; as the film progresses, the shots become longer with the atmosphere becoming subdued as despondency boils away behind the characters’ eyes. A key factor in establishing this developing mood is the soundtrack, which—whilst used sparingly—perfectly reinforces the building anxiety and misery. This all culminates in a borderline funerary dirge in the lead-up to the final act, accompanied by Mayumi Nagisa’s soulful vocals acting as a somewhat mournful swansong.

Whilst the dynamic tone enhances the story, deeply immersing the viewer, it has to be said that the overall pacing never achieves the same amount of congruency. The genre of the film is difficult to tie down with the eventual pace feeling too languid to call it a crime thriller, though at the same time it is not quite character-focused enough to label it as an urban drama. The short 74 minute runtime works against the slow pacing and eventually results in the side plots left unfinished and supporting characters abandoned in favour of quickly wrapping up Minako’s story. In order to constitute such a short length, the plot is forced to rely too much on coincidence to progress the story, which ultimately ends up stretching believability for the audience.

Initially joining Daiei in 1966, Michiyo Yasuda soon graduated from her youth star status to become the queen of the studio’s “ero guro/unique historical drama” era, playing the lead in every single Kanto Woman film as well as starring in a number of the Women’s Secret films among others in the same genre. Yasuda seamlessly portrays her character’s gradual development from a cocky yet naïve street punk to a much more subdued and vulnerable young woman, as the true danger of her brother’s predicament is thrust upon her and she struggles to deal with the emotional travails she finds herself submerged in. Even with the dominance of Yasuda’s Minako in relation to the story, Mayumi Nagisa still manages to steal a scene or two with her charismatic and nuanced performance. It could have been very easy to overact the part of Tamaki, the hot-headed chanteuse, perfectly characterised by a rose and thorns tattooed on her inner thigh, though she handles the part with tact and doesn’t let her character’s exuberance overshadow emotional depth. It is certainly a shame that the focus on such a well-realised character is side-lined and sacrificed in order to tell Minako’s story.

Starring as Amano, Toshiyuki Hosokawa brings much-needed balance to the story, anchoring the situation the girls find themselves in with a stoic calmness. Initially, Amano appears to be a typically hardboiled noir antihero, though Hosokawa manages to imbue his character with a great deal of depth and emotion despite his tight-lipped demeanor. He appears as both sympathetic and threatening to the audience, perfectly mirroring his internal turmoil when it comes to Minako and her brother. Whilst his character is clearly extremely deadly, Amano goes against the violent yakuza hitman archetype. He is a man who greatly values honour and whose name is met with great reverence even by the typically treacherous Hatyama clan. All this has the effect of putting the audience in Minako’s shoes, questioning just how trustworthy Amano truly is, and allows us to enter the finale unknowing of what may eventually transpire.

Overall, Kanto Woman Yakuza is a fascinating entry into the neo-noir genre, perfectly marrying the classical style with the unique culture of late 1960s Japan. Despite its short runtime, the film portrays an impressively deep and complex world, with its slow moody pace perfectly submerging the audience in the bleak, fog-filled backstreets of the nameless port town. With the painstakingly stylish shooting of Akira Inoue, the film is a sumptuous joy to behold and is certainly a hidden gem of this interesting period of pre-1970s Japanese cinema.

More Film Reviews

Rumor has it that musicians sell their souls to the devil and worse represent Satan through their songs. It was a ridiculous idea that still scares the bejesus out of… Summer in Montreal is always an exciting time. Downtown, Ste. Catherine Street is cordoned off from traffic beneath de Bleury for the Jazz Festival, where past years featured free outdoor… Life is a Train Wreck In the final days of 2022, most of us were looking toward 2023 with hearts full of hope, and faith that the moment those… Horror filmmaking royalty collides in Two Evil Eyes (1990): a star-studded yet relatively niche anthology horror from the depraved minds of Dario Argento and George A. Romero. The dastardly duo… Directors Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead blew me away with the debut film Resolution, an eerie tale marked by a foreboding sense of doom. Their follow-up film, Spring, I will admit being… Arguably one of the most celebrated European exploitation subgenres, nunsploitation rose to prominence in the 1970s following The Devils in 1971. Largely driven by Italian productions such as Sister…Shirome (2010) Film Review – Selling your Soul

Tombs of the Blind Dead Film Review (1972): Fantasia Fest 2021

White Noise (2022) Film Review – Arthouse Existential Horror Comedy

Two Evil Eyes (1990) Film review – Defrosting Forgotten Horror History

Synchronic (2020) Film Review: Everyone In The Past Wants To Stab You

The Virgin Witness (1966) Film Review – The Origins of Japanese Nunsploitation

Hi, I have a borderline obsession with Japanese showa-era culture with much of my free time spent either consuming or researching said culture. Apparently I’m now writing about it as well to share all the useless knowledge I have acquired after countless hours surfing the web and peeling through books and magazines.