When it comes to the cinematic phenomenon that was pinky violence, one of the key attractions was its stars: Reiko Ike, Miki Sugimoto, Reiko Oshida, and Meiko Kaji to name a few. Rocketing to the heights of pop culture icons, the media couldn’t get enough of these glamorous women, with at least one of them almost guaranteed to feature in any issue of the premier magazines Weekly Playboy or Heibon Punch throughout the 1970s. Despite Reiko Ike and Miki Sugimoto (arguably the two biggest stars of the genre) leaving the limelight by the end of the decade and seemingly disappearing off the face of the earth, they are still highly celebrated to this day with their cult classic films always drawing in new audiences. However, one star of the period has unfortunately almost been forgotten altogether: Rika Aoki. Very little information exists online about Rika, so in order to learn more about the once-popular star we have tracked down as many magazines as possible from the early 1970s in search of interviews and articles about her.

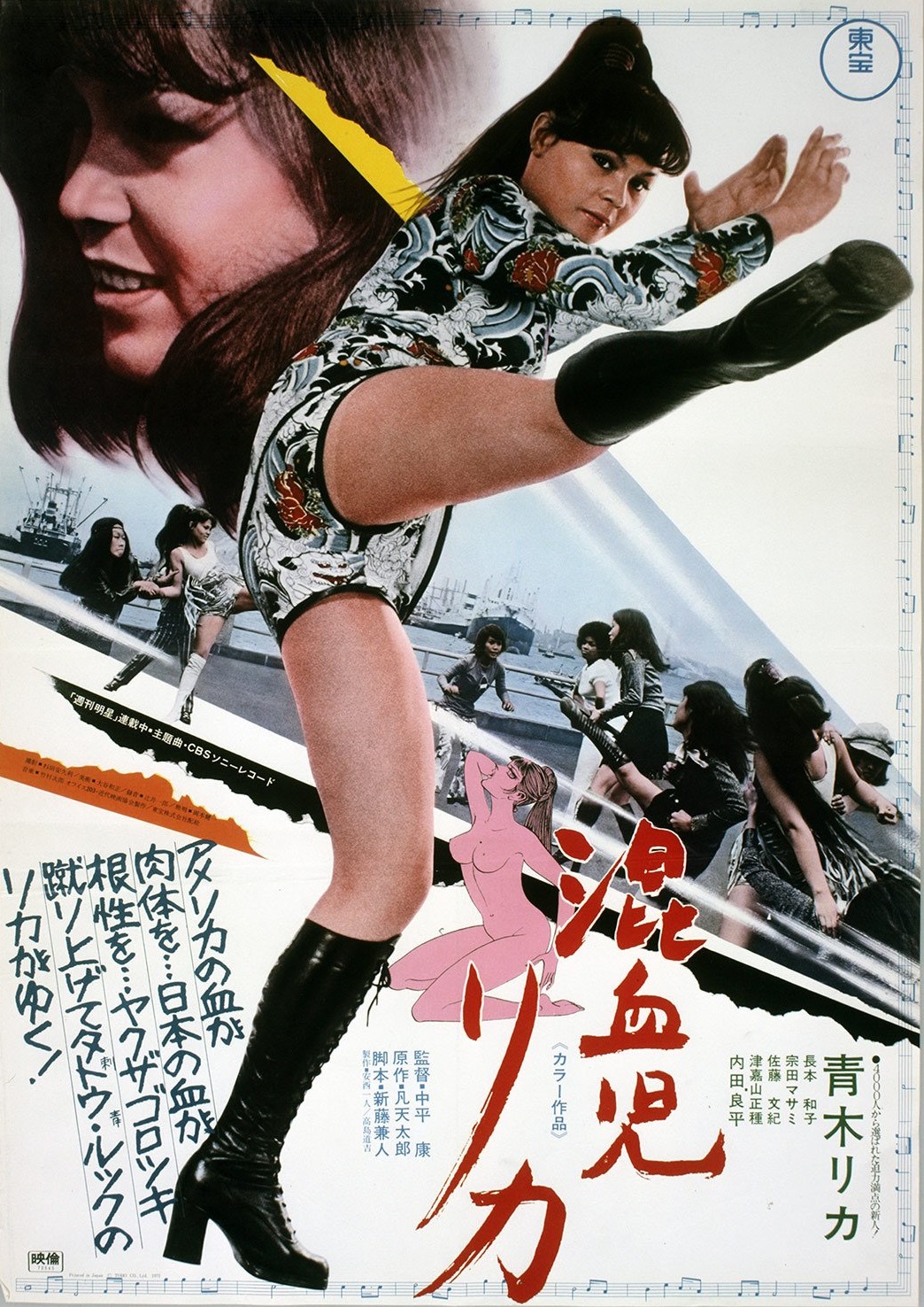

Much of Rika Aoki’s intrigue looking back comes from her almost inexplicably sudden rise to fame: just how did an unknown actress make her debut as the lead role in the Konketsuji Rika trilogy of films? Luckily Rika Aoki’s rise to fame was well-documented due to the unique circumstances surrounding it.

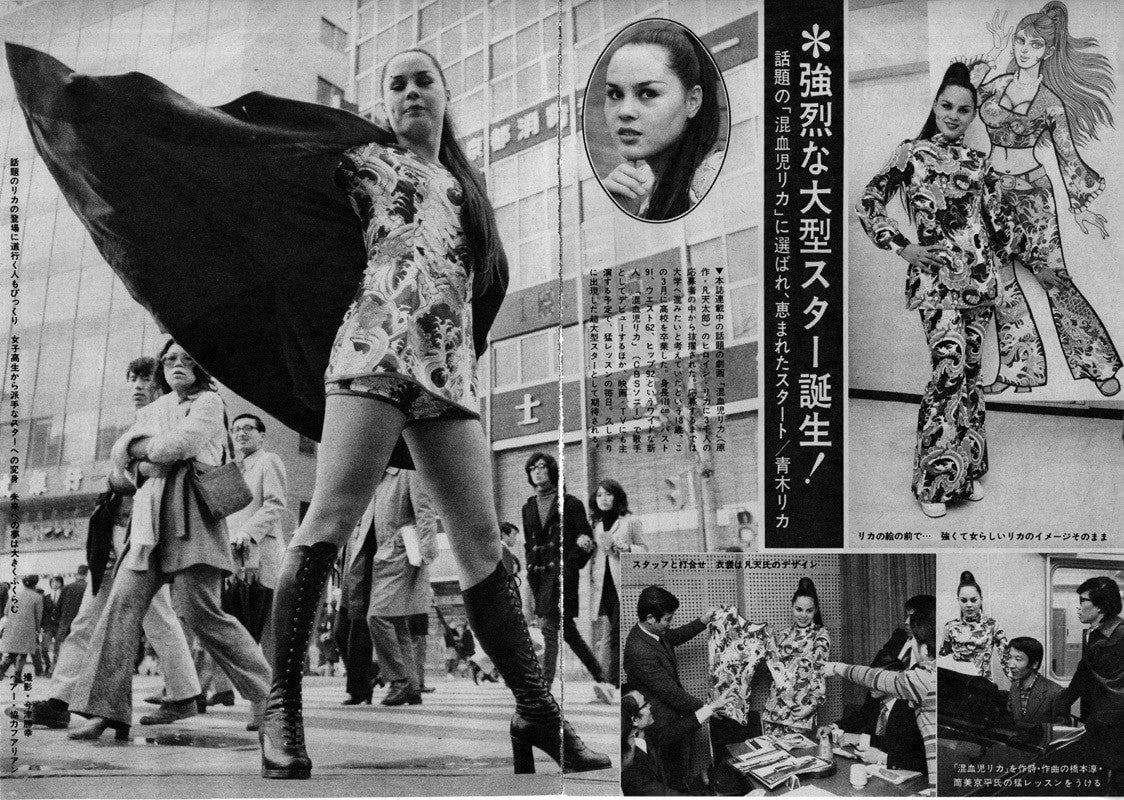

When it was announced that the popular pinky violence manga Konketsuji Rika would receive a live-action adaptation, a novel method was taken to find the lead. The manga, beginning serialisation in 1969 followed the life of a young mixed-race woman (konketsuji was a racial slur against mixed-race people with “mud blood” being the closest English equivalent) as she gradually becomes a juvenile delinquent. The pop culture magazine Weekly Myojo, which serialised the manga, ran an open competition in order to cast the role of the titular Rika. Beating approximately 3000 other applicants, Rika Aoki took the part in February 1972 – selected as ‘the one and only’. Her success came somewhat as a shock to Rika as she admits she didn’t actually make the application herself: ‘My mama was against me going into showbusiness. I guess one of my relatives must have put me forward for the “Konketsuji Rika” contest.’ After winning the competition she said ‘I didn’t think I’d be chosen’. She was only 18 at the time and still had another month before high school graduation, so the prospect of walking out of school and straight into show business must have been both exciting and daunting to her.

Born Sharon-Lee Yoshida (Morris) to an American father and Japanese mother, Rika adopted both the first and last name of her manga counterpart as her stage name. Obviously, her mixed-race heritage was a large factor in her winning the part, though she also stood at an impressively statuesque 5ft7 (the average height for Japanese women is 5ft2), further accentuated by a pair of high-heeled boots, perfectly matching the leggy manga heroine. Taro Bonten, the creator of the manga, was full of praise for Rika saying ‘I never thought I’d find someone so perfect’. Despite this, Rika was quite self-deprecating about her looks and, by the language she uses, it seems like she may have unfortunately faced racism while growing up: ‘I look like a monkey, just like my papa. My younger brother is handsome and looks just like my mama.’ Rika’s legs weren’t just for looking at – her height advantage led to great athletic prowess throughout her high school career. Rika modestly stated ‘I was a track and field athlete in high school, running the 100m in 13 seconds flat and scoring 1.6m in the high jump. I also learned karate.’ In reality, her 12.9 second time placed her 2nd in the national high school record.

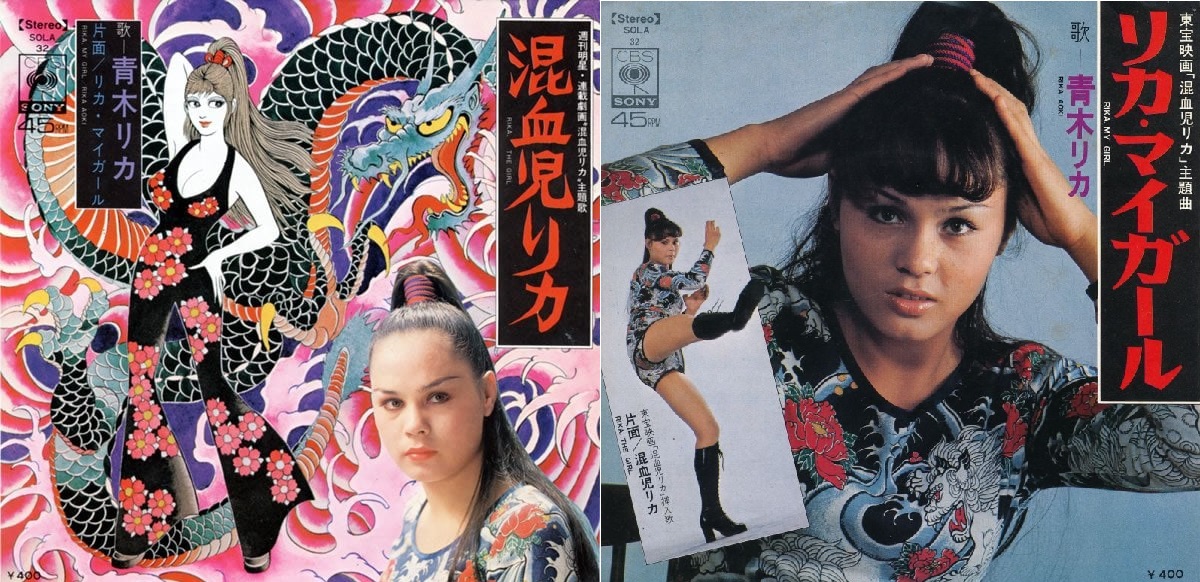

Given Weekly Myojo’s vested interest in their new star, they were keen to give Rika as much publicity as possible leading up to the film. Between her casting in February and initial shooting in October, she enjoyed constant attention in the pages of the magazine. Being a total amateur, Rika underwent extensive training in acting and modern ballet (presumably to achieve the high kicks necessary for the character’s kickboxing-esque fighting style) to prepare for the role. However, she also received training in singing, clearly showing an intention to push Rika to stardom across all disciplines; at the time it was common for top actresses to record at least one single, but that usually came after they were established names. Her first single was released in June 1972, almost a half year before the film’s release to truly kickstart the hype train. At the same time, she also became a regular on TV screens as the “cover girl” for the variety shows Yo! Don and The 11PM Show. This all ensured that Rika was close to becoming a household name even before the film was released – Weekly Myojo stated that she ‘was a hot topic of conversation nationwide.’

In mid-October, work started on the film, though with a 26th November release date the production must have been frantic even by typical pinky violence standards. Rika’s resolve was tested to the limit when she had to regularly endure grueling 20-hour work days beginning at 6 AM and ending at 2 AM the following day. She also had to do all her own stunts which, from the get-go, led to her accidentally being punched in the face and even falling down some stairs, injuring her leg. The hard work and late nights were worth the effort though, and the film was a huge success resulting in a sequel being greenlit almost immediately.

The sequel, Lonely Wanderer, released in April 1973 would prove to be just as popular and ensured a third in the series, Juvenile’s Lullaby, later that year in June. Rika’s media promotion would continue up to this third film, but after its release, she practically disappeared with all attention on her drying up completely. The third film admittedly received a frosty reception, though was that truly enough to finish Rika’s career?

After the inexplicable media silence surrounding Rika throughout the remainder of 1973, she would go on to star in only one more film – playing a small guest role as a sukeban in Toei’s Student Yakuza in 1974. There are many possibilities as to why her attention disappeared: assuming Weekly Myojo’s interest in her only extended to them promoting their own manga, the end of the Konsketsuji Rika film series presumably also meant an end to any promotional deals they had with her. Another possibility is good old-fashioned sexism. Being a successful female star in 1970s Japan was heavily appearance-based (not unlike the idol culture which persists to this day), and whilst the media generally praised her acting performance, the same was not extended to her looks. Apparently, her mixed-race features did not meet the beauty standards of the time, and even though there was no lack of praise for her long legs, the same could not be said for the opinions of her face which were less than flattering.

However, the more likely explanation is that it was Rika’s own decision to leave the limelight. Even after her casting, it was clear that being a star was never truly one of her dreams. When asked if she had any regrets, she said that she had wanted to go to college and eventually teach Japanese in America (where her father lived); in her high school national exams she ranked third in English so this was no pipedream. In Japan, dual citizenship is only allowed for children and has to be given up when they reach voting age (which in the 1970s was 20). This dual citizenship held the key to Rika’s hopes of teaching in America and came with a time limit of October 1973. Perhaps with this date in mind, she later said that if she did not succeed after two years, she would attend college.

Even after the success of the first film, Rika was still unsure if she was truly dedicated to becoming a professional actress and said that she had finally made the decision to go to college, this time with the intention of becoming a simultaneous interpreter. It’s uncertain whether her role in Student Yakuza was intended as a serious attempt to revive her career or just as a final go at acting, but it seems that with a wealth of other options in life, Rika purposely turned her back on acting. A simultaneous interpreter is a high-paying job so with her skill in English it seems like a wise choice to pursue that, rather than gambling everything for the chance to be a film star.

Before she was Rika, Sharon-Lee was just a regular girl, living in a small Tokyo housing complex with her grandmother, mother, and younger brother. Looking back now, it is truly impressive how an inexperienced young woman appeared from nowhere and managed to rise to such lofty heights in such a short period, built on the foundations of nothing more than determination and a few months’ worth of training. Despite nowadays being little more than a brief footnote in the history of Japanese exploitation cinema, back in 1972 and 1973 Rika Aoki stood shoulder to shoulder with her more experienced contemporaries and was quickly embraced by the public. With a short career barely lasting two years and only having four films to her name, Rika was a humble star who burnt bright yet fast. She may not have the extensive filmography of Reiko Ike and Miki Sugimoto under her belt, but that doesn’t mean she was any less of a star. Hopefully, Sharon-Lee realised her dreams of being a teacher/translator and looks back fondly on the brief period when she was the nation’s number 1 high-kicking badass.

More Reviews

Gorenography is a 2021 documentary hosted by director Tony Newton. The documentary delves deep into the world of extreme cinema, divulging an uncensored, unbridled look at this niche underbelly of… Johanna is just twenty years old but struggling with her boring and aimless existence. Disturbing visions start the day she gets fired from her job. Soon Johanna is carried off… Jean Rollin was a French director of fantastique films whose films remained obscure throughout most of his career. Thanks to longtime admirers, his haunting and poetic visions are seducing a… I’m all for enjoying bad films, in fact, some of my favourite films are schlocky B-movies from the 70s. However, I would always argue that these films, whilst terrible, always… Two tragedies combine with unforeseen consequences after Amanda retreats to the country to open an B&B following the death of her husband. With her unwilling daughter Karli in tow, misfortune… READER WARNING: Ghosts starring in this review may contain an excessive amount of exploding glitter. Konnichiwa! Bonjour! What’s the story, bud!? Straight Outta Kanto here, bringing you a big fat…Gorenography (2021) Film Review – A Conscientious Exploration of Extreme Cinema Directors

Dark Circus (2016) Film Review – The Goths Are Alright

Orchestrator of Storms: The Fantastique World of Jean Rollin (2022) Film Review – An Excellent Introduction to the Artistry of an Obscure Filmmaker

Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey (2023) Film Review – Poorly-Written Tripe

The Stranger (2022) – Indie Low Budget British Horror With A Bite

Sick Nurses (2007) Review – An Absolutely Outrageous EVENT of a Movie

Hi, I have a borderline obsession with Japanese showa-era culture with much of my free time spent either consuming or researching said culture. Apparently I’m now writing about it as well to share all the useless knowledge I have acquired after countless hours surfing the web and peeling through books and magazines.