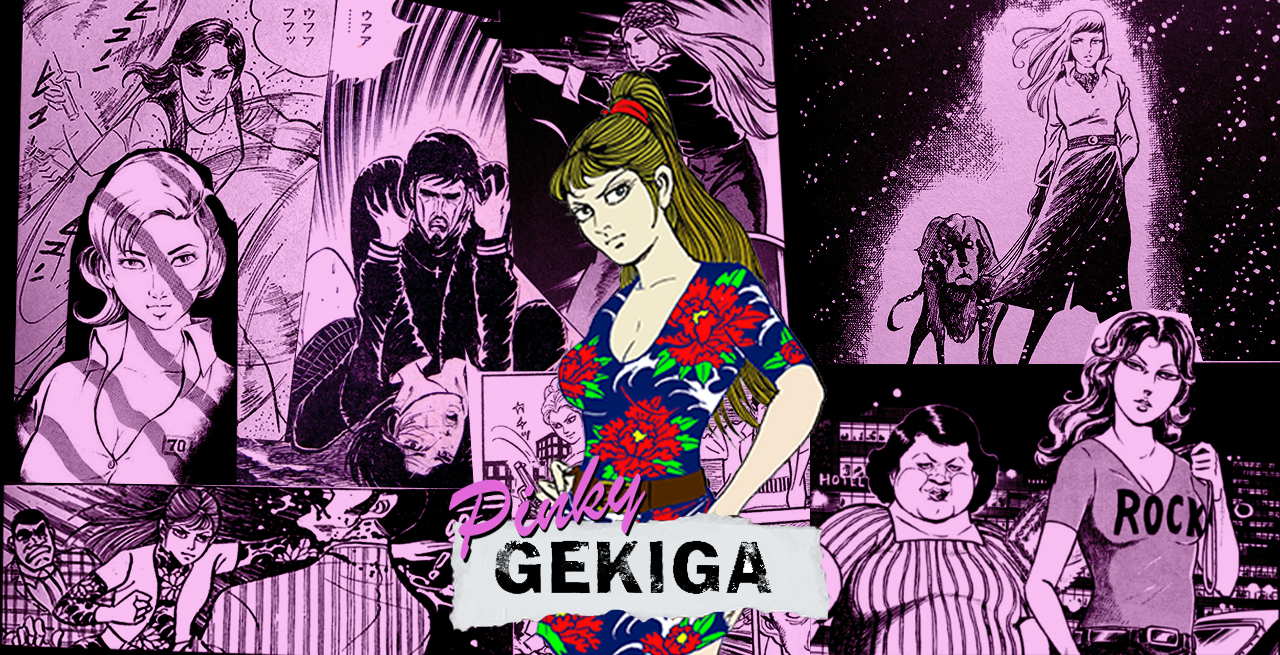

Whilst manga in Japan was certainly nothing new by the 1950s, the efforts of artists such as Osamu Tezuka led to the medium becoming more popular than ever, especially with children. With the extreme popularity of this childrens’ manga only ever growing, the term “manga” itself was quickly becoming synonymous purely with childrens’ manga. Artists catering to a more adult audience at the time felt a different term should be used for their interpretation of the medium; thus, Yoshihiro Tatsumi would coin the term “gekiga” in 1957, literally meaning “dramatic pictures”. Tatsumi and his contemporaries were influenced heavily by films when creating manga, and this new term perfectly encapsulated their style. As adult manga hit its peak in the 1960s and 70s, gekiga would become the dominant form, offering fast-paced and gritty stories which, unlike childrens’ manga, tended to rely more on visuals and atmosphere as they did dialogue. Gekiga demonstrated clear cinematic influences from mirroring popular cinema trends at the time, focusing on neo-noir crime stories and violent samurai tales most prominently.

With such a link between gekiga and film, it is no surprise that in the 1970s, the two mediums would collide with popular gekiga stories being adapted for the big screen. In the 1970s, pinky violence, roman porno, and other exploitation genres dominated adult cinema, and the similar sex and violence-filled gekiga so popular with readers proved the perfect material for studios looking for the next big hit. Already built on the foundation of a successful manga with the name and brand recognition amongst readers, most of these film adaptations would go on to become some of the most celebrated of their genre throughout the decade, showing the value and power gekiga had. In our previous ranking of all of Toei’s pinky violence films, 75% of the top tier consisted of gekiga adaptations. Below we look at the the gekiga of the era which received film adaptations in the exploitation genre and compare how well the source material was realised on the big screen.

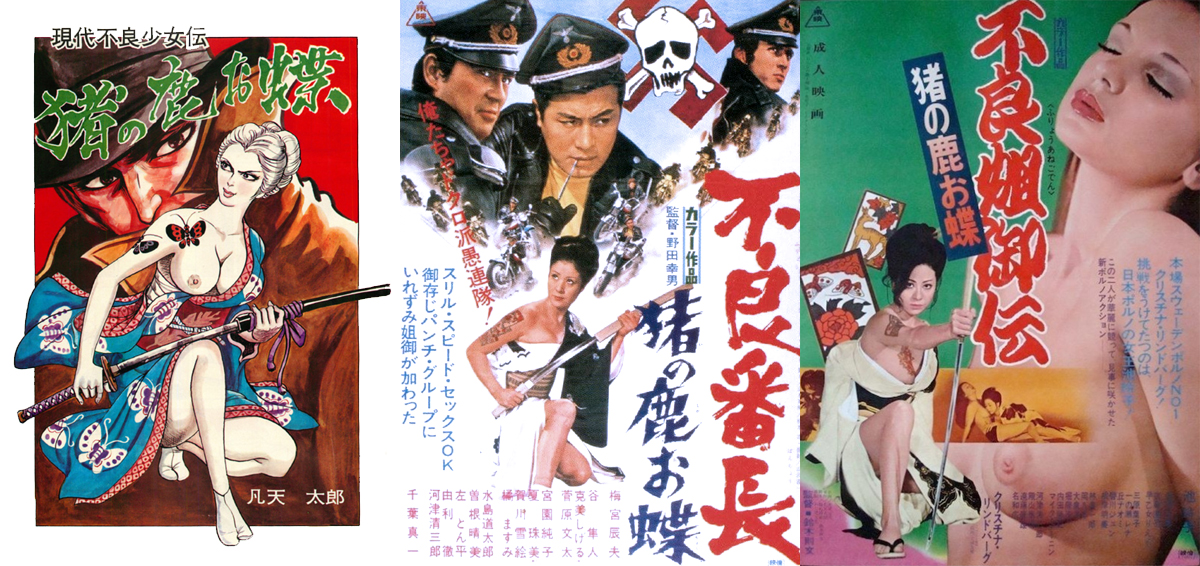

Ocho Inoshika (1968-1969)

(猪の鹿お蝶)

Taro Bonten – Manga OK

Ocho Inoshika tells the story of the titular Ocho, a travelling gambler, as she navigates her way through a dark, neon soaked underworld filled with gangsters, pimps and killers. When she encounters a cocky gangster on a train causing a hassle, she is quick to put him in his place and humiliates him in front of everyone. When he later returns with some backup to take his revenge, they realise that Ocho’s bite is just as severe as her bark as she savagely guns them down. In doing so, she soon attracts the attention of the yakuza boss who is reluctant to let the attack go unpunished. Determined to fight back she later becomes privy to an underground prostitution ring led by the yakuza and takes on the role of a sort of vigilante, determined to protect the vulnerable women who have fallen victim to the gang, whilst also dealing out her own justice and revenge.

Despite being the protagonist of the manga, the main story unfolds somewhat separately of Ocho. At the end of the day the yakuza’s main focus is on pimping out vulnerable women rather than taking down Ocho. This gives the reader the feeling of a very lived-in world where the characters have their own lives and motivations outside of the protagonist. This also gives Ocho her chances to strike out at the yakuza as their backs are figuratively turned. Whilst she is adept with a katana and is also a decent shot with a pistol, Ocho’s main weapon is her mind as she is able to deviously outsmart her enemies. Whilst the manga does have its fair share of violence and gore, Ocho’s sharp tongue and even sharper wit are what really come to define her character. Artist Taro Bonten’s design of Ocho immediately attracts the reader’s attention with her head of bright blonde hair and tattooed left arm which becomes exposed when she draws her sword; though his artwork really excels when it comes to Ocho’s facial expressions, where he is able to wordlessly convey so much with just a cocky smirk or a cunning side glance.

Ocho’s first appearance on the big screen actually came in 1969 when she appeared as a side character in the second installment of Toei’s Delinquent Boss series which focuses on a male biker gang. When the gang attempt to groom and pimp out a group of naïve young women, the yakuza aren’t too happy about them muscling in on their turf when it comes to the prostitution business. As the gang fight back they also encounter Ocho who has her own beef with the yakuza and their treatment of women. Whilst it isn’t immediately at the forefront of events, the film does quite accurately adapt the general story of the manga, albeit with the main focus on the biker gang who have effectively walked in halfway through Ocho’s own quest for vengeance. Ocho here is played by Junko Miyazono who is perhaps best known for her somewhat similar role in the Legends of the Poisonous Seductress series. Miyazano does a good job of portraying Ocho’s wit and quiet confidence, though with the Delinquent Boss series being of a fairly light tone, her portrayal is made a little tongue-in-cheek to match. Here Ocho doesn’t slice up her enemies with a sword but instead throws playing cards almost like shuriken, leading to her seeming quite cartoonish at times like an animé character with her “special move”.

In 1972 the character would return for Sex & Fury, though this time contemporary Japan would be swapped out for the Meiji era and Ocho given an entirely new backstory where she is attempting to hunt down the men who killed her father when she was a child. As a standalone film, Sexy & Fury is regarded as one of the best pinky violence films ever made, though as an adaptation of the manga it arguably ends up deviating too far from its source material and barely feels related at all. Whilst the character of Ocho is perfectly realised by Reiko Ike in possibly the best performance of her career, the sole focus on this new revenge story is out of place when compared to the manga, feeling more like a Lady Snowblood imitation. Sex & Fury would receive a sequel, Female Yakuza Tale, also based in the Meiji era which shifts the attention back to the original manga as Ocho is once again in familiar territory, battling a yakuza-led prostitution ring. Perhaps this is the reason that, in Japan, Female Yakuza Tale has historically been the more favoured of the two films.

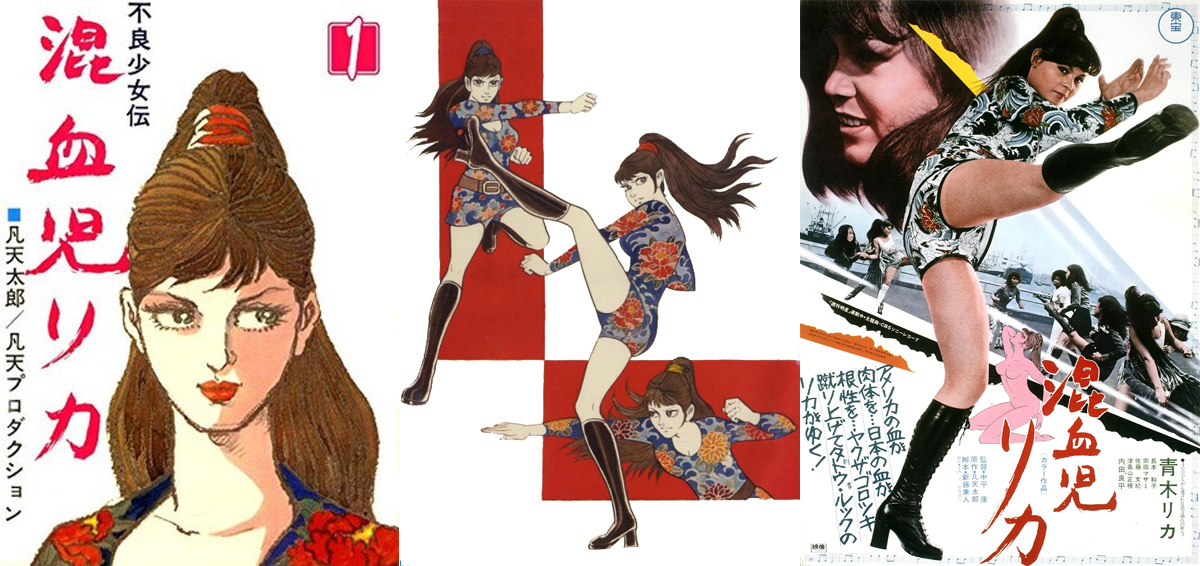

Konketsuji Rika (1969-1973)

(混血児リカ)

Taro Bonten – Weekly Myojo

Konketsuji Rika follows the life of the mixed race delinquent girl Rika, beginning with her conception when her mother was raped by American soldiers stationed in Japan. We then follow Rika through her childhood and teenage years as she suffers racism from her peers; has to come to terms with her mother working as a prostitute; before finally focusing on her as a young woman. With her difficult upbringing Rika has had to learn to fight for herself; however, this desire to constantly fight comes at a disadvantage to her when a group of men attempt to molest her one night. She strikes back, beating them with a metal pole but doesn’t realise they belong to a yakuza gang. With Yokohama’s underworld after her she must fight for her life, and the eventual killing of a gang boss lands her in reform school. It is here where her fate as a sukeban is sealed and when she is back on the streets assembles her own gang and becomes a force to be reckoned with.

Taking the novel David Copperfield-esque approach of beginning the manga with Rika’s conception and subsequent birth was a brave and risky undertaking, yet it pays off, giving the chance for an unprecedented amount of detail in Rika’s character examination as we see how every event in her upbringing comes to effect her later in life. Rika is portrayed with generous realism; whilst similar characters at the time were shown as almost invincible superwomen, Rika is very much your regular young woman and comes with all the angst and naïvety you would expect of such a person. The massive amount of attention dedicated to Rika and her struggle also gives the manga a level of feminism not usually present in media at the time. Whilst manga about strong women was certainly nothing new, their characters were often used for their physical appeal and weren’t explored with nearly the same amount of emotional detail. Opposing this more gentle look into the emotions of a young woman is the extreme amount of bloody violence as people are beaten, stabbed, shot, dismembered, decapitated, and even crushed beneath the wheels of a truck all with a flurry of toothbrush-bristled blood spray drenching each panel, not too dissimilar to a 2000AD comic.

In 1972, the manga would receive the first in a trilogy of film adaptations courtesy of Toho. At face value, the film couldn’t be more perfect and is so accurate to the manga that, at many points, feels like entire pages have been used as a story board; actress Rika Aoki’s resemblance to her manga counterpart is also borderline uncanny. However, the medium of film isn’t quite the same as manga, and in relying on the manga so absolutely, there are massive problems with pacing and scene transition. The manga was published in short chapters on a weekly basis, so jumping from one location to another never feels too unnatural, although any sense of natural flow is eliminated in film form. Rika Aoki was cast with no prior acting experience, but in many ways this is a boon rather than a disadvantage, as her natural deer-in-the-headlights portrayal lends itself well to the character’s inherent naivety. Whilst there are plenty of fights with Rika’s long legs acting as the perfect weapon, the film never quite reaches the same levels of brutal violence as the manga.

Sasori (1970-1975)

(さそり)

Toru Shinohara – Big Comic

When Nami Matsushima’s undercover cop boyfriend is having some trouble securing a bust on a yakuza gang, he decides to use her as bait. Sending her unaware into the clutches of the yakuza, he allows her to be raped by them before bursting in and arresting them. Needless to say, Nami is furious at how she has been used and attempts to stab him outside the police station in revenge. After failing, she is arrested and the woman once known as Nami becomes the deadly prisoner dubbed “Sasori” (Scorpion) by her fellow inmates – a furious husk of a woman whose entire being is dedicated purely to seeking revenge on her boyfriend and the police force who enabled his actions. Sasori is both feared and reviled by her fellow inmates and prison guards alike. After several attempts on her life, it is clear she will do anything and kill anyone who stands in her way.

Much of the manga can essentially be split into two situations: chapters where Sasori is in prison, and chapters where Sasori is on the run. Given the differing dynamics of these situations, the manga keeps a constant level of excitement throughout and never ends up feeling stale. The prison sections are deeply claustrophobic and filled with hostility, with events feeling like a tinderbox which could ignite any second – every action Sasori takes constantly has the possibility of ending in extreme violence. Opposing this are the fugitive sequences where the tension is continually ramped up as Sasori desperately seeks to not only evade her captors, who are only ever a couple of steps behind her, but also carry out the revenge mission she has dedicated her life to. Toru Shinohara masterfully captures Sasori’s differing emotions, depicting her anger and ruthlessness but also the sheer desperation she has to complete her mission. The prison setting is rendered incredibly atmospheric, almost making the reader feel like they are incarcerated alongside Nami with the internal darkness and oppressiveness accurately captured; alongside this are external illustrations making an effort to show its imposing walls giving a feeling of hopelessness.

When director Shunya Ito adapted the manga in 1972 with Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion, the first in a series of four films, he used the manga more as a springboard to tell his own interpretation of the story rather than making a direct page-to-screen adaptation. In his hands, the story would be elevated to borderline arthouse levels with avant-garde filmmaking techniques taking influences from kabuki theatre, and a new bitter political undertone running throughout challenging modern Japan’s ideas on justice and authoritarianism. Meiko Kaji was given the role of Sasori who takes the bitterness of her manga counterpart and increases it to levels so extreme that her borderline-mute interpretation Sasori more resembles a revenge demon than a woman. Despite these departures from the manga, it still remains incredibly faithful, taking just the right amount of artistic license without compromising the original story or tone. Don’t forgot, too, to check Lisa’s ranking of these films.

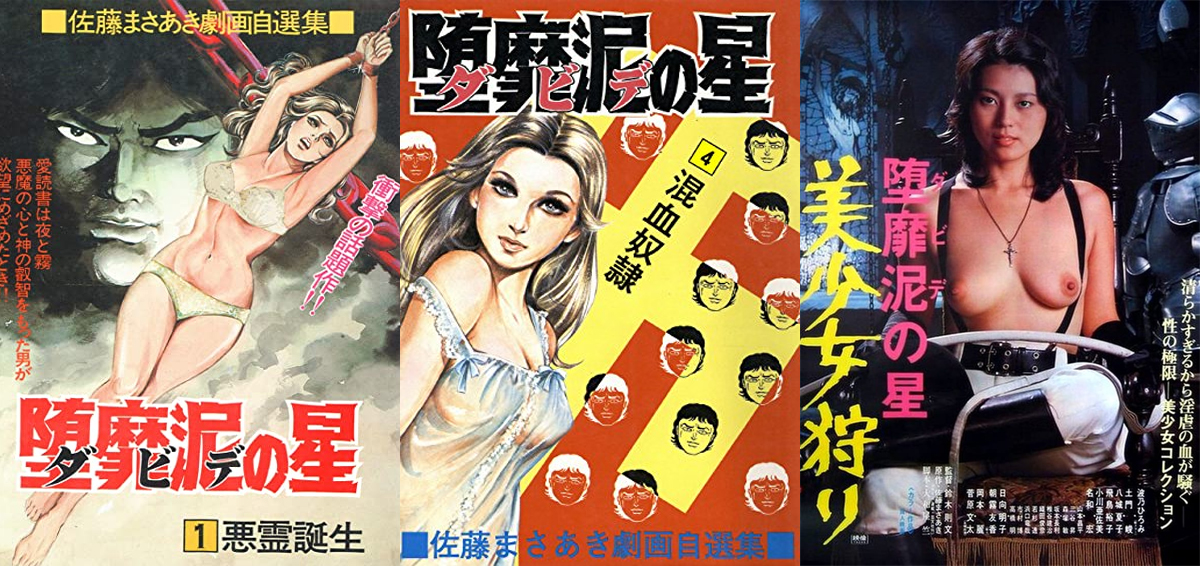

Fallen Star of Mud (1971-1976)

(堕靡泥の星)

Masaaki Sato – Manga Heaven

Fallen Star of Mud asks the question whether evil is genetic or environmental. When a maniacal rapist and murderer escapes from prison, he breaks into a couple’s house and ties them up before raping the woman in front of her husband. When she discovers she is pregnant a few months later, there is a very high chance the child belongs to the rapist. Her husband, knowing this, becomes abusive to his wife, seeing her as nothing more than a slut after being raped; once his “son” Tatsuya is born, he takes out his hatred on him as well. Growing up with an abusive father, and with a seemingly predisposed degeneracy from his biological father, Tatsuya becomes obsessed with sadism and cruelty. This comes to a head when the holocaust is brought up in history class, and instead of feeling remorse for the victims of the Nazi regime, he sympathises the Nazis. After his mother’s eventual suicide due to years of abuse, he finally murders his father. Inheriting a vast fortune, Tatsuya is then free to indulge all of his sickest desires whilst outwardly portraying himself as a youthful playboy. He soon begins a spree of not only kidnapping, raping, and killing women, but also a desire to corrupt the pure.

Masaaki Sato has self-admittedly never been able to draw women very well, so throughout his career, the portrayal of female characters has almost always been undertaken by his assistant (who during this period was Tadashi Matsumori). The contrasting art styles, rather than being jarring, actually enhances the manga, with the ugly and deranged Tatsuya perfectly juxtaposing the doe-eyed beauty and innocence of his targets. Throughout the manga, we are assaulted with disturbing images of war and suffering as Tatsuya’s sick daydreams of historical atrocities are portrayed almost like newspaper clippings to the reader. By offering such in depth examinations of Tatsuya’s thoughts, the manga is both fascinating and disturbing as the reader learns how his mind works. Perhaps even more disturbing than the events of the manga are Masaaki Sato’s reasons for creating it in the first place. During the time, like Tatsuya, he was drawn to sadism and admitted that he was extremely tempted to rape women and that this manga was an outlet to sate his impulses. Reading the manga knowing that Sato was, in some ways, using it as a way to express his own feelings and desires makes it even more shocking as the lines between the fictional Tatsuya and reality are blurred. Whilst it is comforting to be able to tell yourself that Tatsuya is a fictional monster, it is chilling to know that so many of his actions came from the mind of someone who clearly fantasised about carrying them out themselves.

In 1977, renowned pinky violence director Norifumi Suzuki was eager to make an adaptation of the manga. After being denied the opportunity by Toei, the chance finally came in 1979 courtesy of Nikkatsu with Fallen Star of Mud: Beautiful Girl Hunting. Regarded as one of the most extreme roman porno films of the 1970s, Suzuki doesn’t hold back in his faithful adaptation of the disturbing manga. With the decision to portray events in a nonlinear fashion, with frequent flashbacks revealing the events which led to the formation of Tatsuya’s cruelty, the film works well as a character examination whilst also ensuring the main focus is on his present actions. Shun Domon does an excellent job of portraying both a charismatic and handsome playboy one second and a dead-eyed psychopath the next, mimicking the cold stare of his manga counterpart with haunting accuracy. It has to be said however, that the film lacks the edge of the manga, whilst it initially appears shocking with its drawn out scenes of bondage and sexual abuse, once you strip them away it all feels very surface level. Whilst the flashbacks reveal the development of Tatsuya’s psyche, we never get a proper exploration of his actual thoughts. We know why he is carrying out these attacks, how he obtains satisfaction from them, but we are missing a true look into his life. Perhaps only a man like Sato, who shares similar thoughts with Tatsuya, is able to properly deconstruct such a character. In place of this missing link, Suzuki instead attempts to make a comment on post-war Japan and the influence of religion. Whilst these are interesting alternative takes on the story, they are never properly developed with the sex scenes given priority over all else.

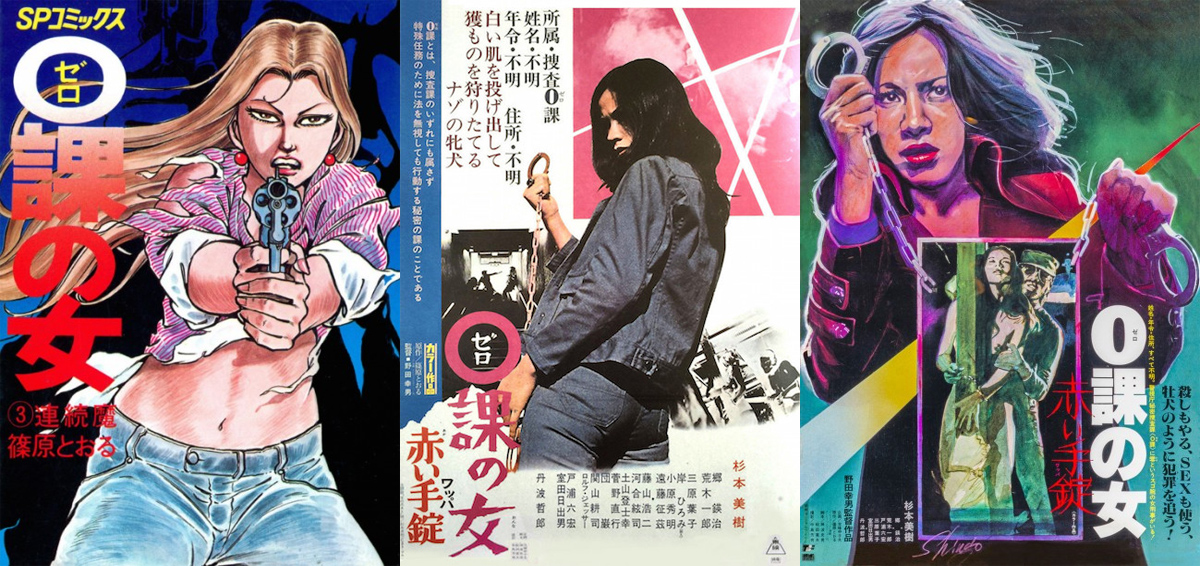

Zero Woman (1973-1977)

(0課の女)

Toru Shinohara – Leed Comic

In the fictional N ward of Osaka, crime has become so rife that the police force has resorted to creating a new division – Section Zero – which is intended to deal with cases requiring extrajudicial force or of a political nature not suited to the regular police. The Section Zero detective known only as Rei, or “Zero Woman”, is permitted to use any means necessary to carry out her missions, even if that involves murder. The one caveat to this freedom is that Rei technically does not exist, and receives no assistance or backup whatsoever from the police. Working as a lone wolf, Rei has to rely on her cunning in her deep undercover cases which deal with kidnapping, murder, robbery and more.

Dirty Harry, as in most of the world, was a massive hit in Japan and its influences were felt almost immediately with this new character type, dubbed the “outlaw detective”, becoming a popular focus throughout 1970s gekiga. One early adopter of this character was Toru Shinohara, and Zero Woman tackles many similar themes seen in Dirty Harry. Whilst in Dirty Harry, the right wing avenger is ostracised from the police force, Zero Woman is instead sponsored on an institutional level. Whilst the manga certainly doesn’t lack action, the main focus of the stories is on infiltration. Since Rei has no backup, she has to carefully insinuate herself into each situation, taking care to remain inconspicuous and avoid suspicion. As a result, the manga is incredibly suspenseful and the resolution of each case is extremely satisfying as so much care is taken by Rei to slowly build her advantage. The manga never really makes any attempt to criticise the extreme measures taken by Section Zero and instead almost promotes them as a just and necessary method to deal with crime. By using a fictional ward, allowing a more dystopian portrayal of the world, the moral implications of state sponsored murder are reduced, although there is still a degree of nihilism undercutting the story.

Following the success of Female Prisoner Scorpion, it is natural that Zero Woman would be next on the list to receive an adaptation courtesy of Toei. In 1974 Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs would be released with premiere Toei actress Miki Sugimoto playing the role of Rei. Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs takes partial inspiration from one of the manga stories and focuses on the kidnapping of a politician’s daughter (in the manga it is the chief of police’s daughter). Given the sensitive political nature of the situation, as well as the police and politician’s desire to kill the kidnappers to cover up the case, it is handed over to Section Zero. In the manga Rei’s past is kept a secret, though she receives a backstory in the film. She starts out as a cop but when she is attacked by a rapist, she takes matters into her own hands. Little does she know, however, is he is an American soldier and his death risks a political incident. She is stripped of her badge and imprisoned, however she is soon approached by Section Zero who offer her freedom in exchange for becoming an agent for them. This new backstory actually gives a massive tonal shift to the story: in the manga, it is assumed that Rei willingly acts as Zero Woman driven by her desire for justice, whereas in the film she is not really given a choice. In order to infiltrate the kidnappers, Rei must allow herself to be raped. Whilst in the manga she has to occasionally use her body to her advantage, the fact that she is a somewhat unwilling agent in the film feels like Section Zero is just as culpable for her rape as the kidnappers. With the sheer amount of rape and sexual abuse throughout the film, this has the effect of making the already nihilistic proceedings even more severe and mean-spirited. In the manga, you always feel like Rei has her plan sorted and is waiting for the right moment to strike, but in the film it feels like she has been thrown to the dogs by Section Zero as an expendable tool.

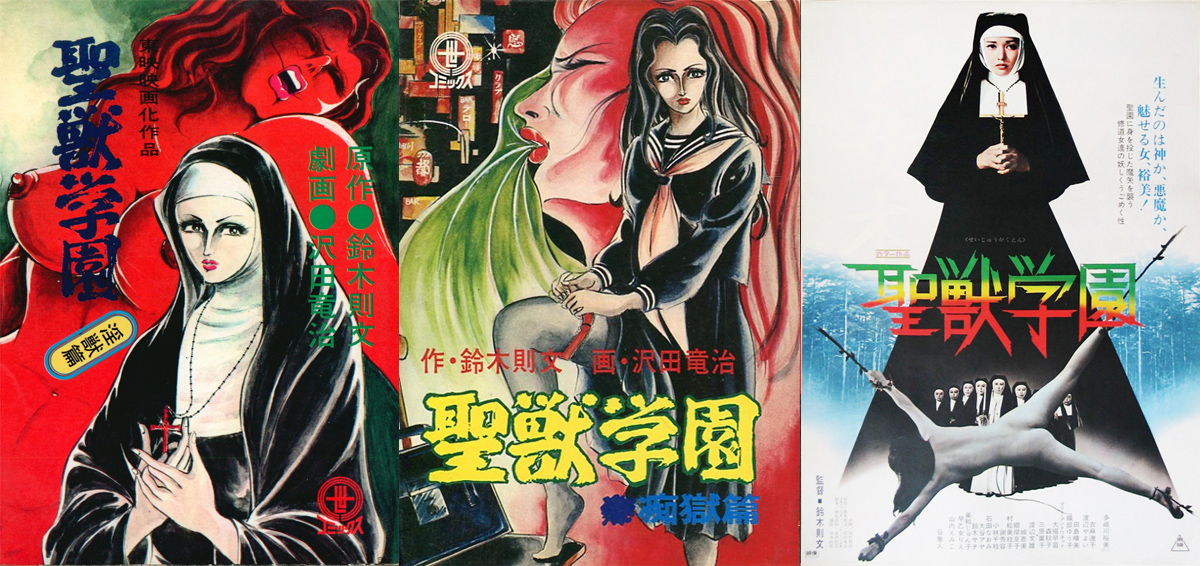

School of the Holy Beast (1973-1974)

(聖獣学園)

Norifumi Suzuki & Ryuji Sawada – Comic & Comic

After a girl’s mother joins a convent and mysteriously disappears, she decides to enter the convent herself to try and get to the bottom of what happened to her. Formerly a juvenile delinquent, she has to rely on all of her street-smart to survive in the nightmarish convent. Soon after joining, she is exposed to a culture of flagellation, sexualised corporal punishment and a lesbian mother superior. She has to constantly fight to survive, but the worst is yet to come when the bishop visits – a depraved man who after feeling that god has abandoned him decides to take out his hatred on the female members of the church.

After Toei’s success with the adaptation of Sasori, they were keen to recreate this success with more gekiga adaptations. Rather than choosing another popular manga to adapt, they would instead create their own bespoke magazine Comic & Comic in a partnership with publisher Tokuma Shoten. Perhaps in order to make the adaptation process simpler, or just to keep loyalty to their own staff, most of the manga in Comic & Comic would be written by some of Toei’s top screenwriters and directors at the time. Toei approached their most popular pinky violence director at the time, Norifumi Suzuki, and asked him to propose a story full of sex and violence, specifically concerning delinquent high school girls in order to make an adaptation which would almost be guaranteed success with the popularity of sukeban cinema. By this time. Suzuki had already created the Terrifying Girls’ Highschool series of films and saw little reason in rehashing those ideas. Instead, he made the decision to fuse the Japanese pinky violence genre with the European nunsploitation genre (specifically Mother Joan of the Angels) and create School of the Holy Beast.

Whilst Ryuji Sawada is hardly a well-known artist nowadays, he did have some success in the 1980s with his erotic, borderline adult orientated manga. It is this skill that he began honing in the 70s that proved a perfect accompaniment to Norifumi Suzuki’s tale of religious sexploitation. Whilst it is far from being pornographic, Sawada’s knowledge of the erotic really aides in the inherent sleaziness required by the story. He is able to convey a large range of emotion in his artwork, further giving the manga a cinematic feel as the art is left to speak for itself with a minimum amount of expositional dialogue required. Whilst a lot of the focus is on sex, the style is still visually sumptuous with a focus on atmospheric lighting giving a religious motif – a theme that Suzuki would double down on with his film adaptation. The manga perhaps contains a direct reference to Mother Joan of the Angels with the character design of the bishop seemingly based on actor Mieczysław Voit. Whilst the initial inspiration comes from Mother Joan of the Angels, not much is shared with the film and instead it seems like Fallen Star of Mud was more of an influence. Focusing of the aspects of religious purity present in Fallen Star of Mud, Suzuki uses the suffering caused by WW2 as a trigger for the bishop, and with this crisis of faith and abandonment of god, he follows a similar descent into sadism as Tatsuya from Fallen Star of Mud.

Needless to say, since the manga was created purely with the intention of film adaptation, the film version is possibly the most accurate any manga adaptation could ever be. The visuals perfectly match the gorgeously environments portrayed by Sawada, lighting the dank convent sets with bright splashes of colour reflected through stained glass windows, making it almost seem like a painting. Yumi Takigawa is given the lead in her first ever acting role and steals every scene she is in, with a natural wide-eyed vulnerability. At times, however, the film can go a little over the top and it is hard to take serious the more extreme events. Suzuki has always been one to try and inject a little humour into his films, though in this case it seems at odds with the quieter and more sombre tone of the manga.

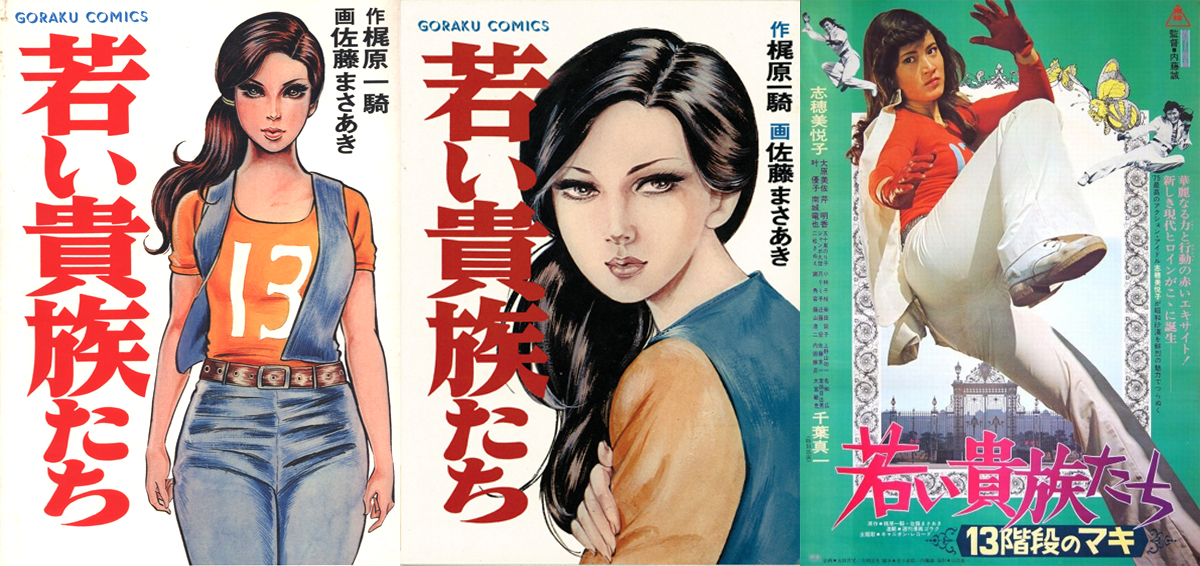

Young Aristocrats (1974-1977)

(若い貴族たち)

Ikki Kajiwara & Masaaki Sato – Manga Goraku

When a struggling manga artist meets the delinquent Maki at a food-stand he is immediately drawn to her. When he encounters her again he witnesses her battling a fearsome girl gang and gaining the upper hand using her martial art talents. At that moment, she becomes his muse as he takes it upon himself to depict her exploits in ink. Following Maki’s story, we meet her gang the “Stray Cats” and learn of her dream of becoming a professional female wrestler. The main story truly unfolds when Maki and her gang end up battling a stuck up rich girl. Little does Maki know, the girl is actually from a powerful aristocratic family with ties to the yakuza and soon finds herself on the backfoot as the girl is able to use both her aristocratic power and underworld connections to imprison Maki on false charges and pass her gang over to ruthless yakuza pimps. Throughout the manga, Maki must go on a mission of revenge and survival, fighting her way to justice with her fists and nunchucks.

For Young Aristocrats, the collaboration between Ikki Kajiwara and Masaaki Sato proved to be a match made in heaven. Masaaki Sato’s manga typically tends to be fairly verbose and dialogue-heavy, which is fine for the hard-boiled detective manga he is best known for, though would have felt clunky and out of place in this action-filled story of a female delinquent. Ikki Kajiwara on the other hand specialised in wrestling manga, and with his involvement, Young Aristocrats is filled with slick and highly kinetic fight scenes – albeit at times these fight scenes can become somewhat excessive. As with Fallen Star of Mud, Tadashi Matsumori handles the female character art and gives Maki, as well as the other members of her gang, attractive and unique designs. It has to be said, however, that Masaaki Sato’s male character designs are far less varied and at times the reader must rely on a character’s clothes to tell them apart. The manga manages to expertly pair blisteringly fast-paced action with slower overall plot development, giving it a well balanced mix of excitement and detail. Unfortunately, interest in the manga waned by 1977, presumably due to the film being released so early on during the serialisation, and it never received a proper ending.

When the manga was adapted in 1975 as Young Aristocrats: Maki of the 13 Steps, the role of Maki almost seemed to have be written specifically with Etsuko Shihomi in mind (Toei’s number one female martial arts star). Like her manga counterpart, Shihomi was adept with nunchucks and had built a hard-as-nails reputation for herself starring in the Sister Street Fighter films. However, she had also built a reputation as a hero, and there were initial fears that portraying a sukeban may harm her career. Whilst Shihomi is physically perfect for the role of Maki – further enhanced by a spectacular pair of platform heels – she never quite manages to sell the ruthlessness needed of her character: Maki is a figure who supposedly strikes fear into the hearts of even the most vicious sukebans but Shihomi’s portrayal feels far too genial to portray this aspect of the character. The film does a good job of covering the essential plot of the manga, managing to include most of the standout sequences, though it does ignore the overarching plot of Maki hoping to become a professional wrestler. That being said, 78 minutes isn’t really enough time to properly give

each scene the attention it deserves and a number of quite key events have to be rushed through. Ideally, it would have been better to spread the story across two films, however, with sukeban cinema falling out of favour by 1975, it is lucky that we managed to even get this single film.

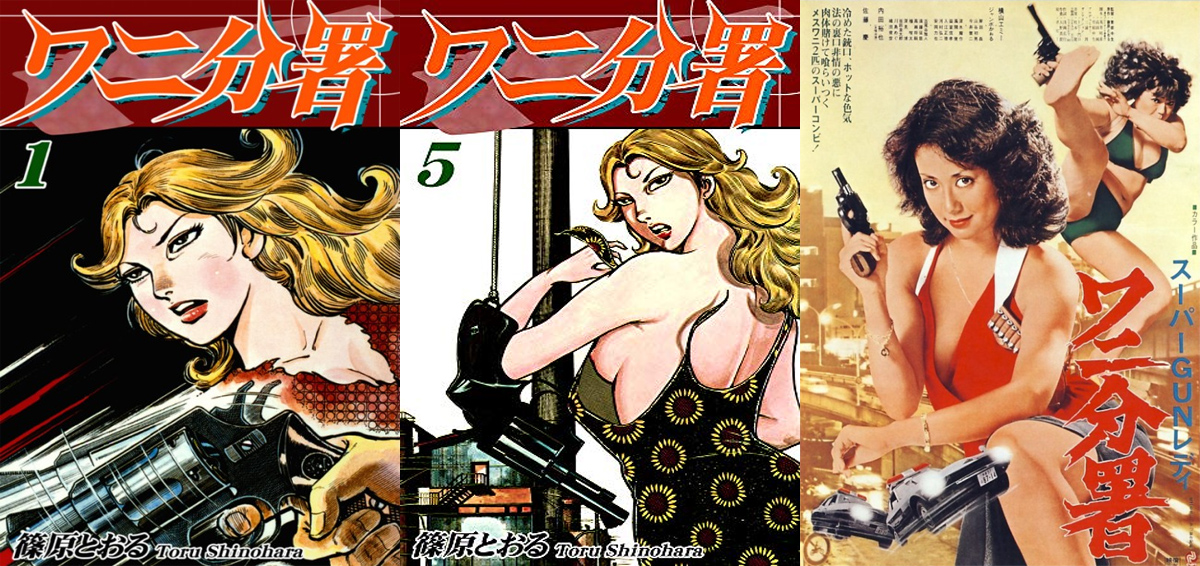

Crocodile Branch (1978-1981)

(ワニ分署)

Toru Shinohara – Weekly Playboy

Crocodile Branch centres around two female detectives working for the undercover 82 branch of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police, based in a secret underground bunker. Mika is the brains of the operation and is a crack shot, but can often be extremely reckless and doesn’t respond well to authority; her partner, the plus-size Rin, provides the brawn, though is mainly present to make sure that Mika stays in line. The two detectives work on a variety of cases from murder, organised crime, extortion and terrorism, to strange cults, using their unconventional, and often highly violent, methods to great success. Part way into the manga, Mika’s backstory is revealed: her young son was murdered by a corrupt cop when he walked in on him raping his mother. In her mission to find the identity of this cop and bring him to justice, she received facial reconstruction surgery and joined the 82 branch. With this revenge constantly on her mind, she forever hopes that each case she tackles might be the case where she encounters him again.

Toru Shinohara takes the general basis of his previous Zero Woman manga, strips away the murky nihilism and moulds it around a much more light-hearted buddy cop tale. If Zero Woman can be compared to Dirty Harry, then Crocodile Branch is definitely the equivalent to Lethal Weapon. The feisty Mika and Rin have a brilliant snappy rapport, never too far from being at each other’s throats, yet neither would turn away from taking a bullet for her partner. As always, Shinohara’s art style is on top form especially with the behemoth that is Rin, showing her bulging muscles as she wrestles a perp into submission. He also embraces the lighter tone in his art, giving Mika some brilliantly exaggerated facial expressions to add a bit of comedy when they off duty. Each case in the manga is brilliantly developed with excellent pace and detailed to flesh out the stories to an extent where any of them could easily be portrayed as a standalone film. Crocodile Branch is also extremely high on action very much showing an influence from American thrillers at the time and much like these thrillers, is also high in sex. With Crocodile Branch serialised in Weekly Playboy, it is perhaps unsurprising that each case includes a couple of sex scenes.

In 1979, Nikkatsu would adapt the manga as Super Gun Lady: Crocodile Branch no doubt hoping to copy the success of Toei’s own Toru Shinohara adaptations earlier in the decade. The opening of the film is an exact recreation of the manga and, like the manga, is a great introduction to the character of Mika and her reckless nature as she drunkenly crashes her car through the side of an innocent family’s house. Emi Yokohama and Kaoru Janbo are brilliantly cast as Mika and Rin respectively and bring a very natural chemistry to their partnership. Whilst the film does a great job of accurately portraying the manga characters (especially with Kaoru Janbo who was the first women’s kickboxing champion), the story on the other hand is severely lacking. Instead of adapting one of the cases from the manga, the film is adamant on creating its own story surrounding the blackmail and apparent suicide of a powerful businessman. Unfortunately, without Toru Shinohara’s involvement, it is very slapdash and convoluted, relying mainly on coincidence to drive the plot forward. It seems Nikkatsu were more focused on the sexual aspects of the manga when they chose Chusei Sone to direct, who had almost exclusively built his career on roman porno and pinku films – probably most notably the Angel Guts series. It is perhaps no surprise then that the film eventually devolves in the second half into an excuse to show lots of women being raped and molested when a trio of sadistic criminals hold a bank hostage. Mika and Rin are almost completely disregarded at this point and the film which started off as a fun buddy cop romp descends into borderline rape porn.

More NSFW Reviews

Covering all things scatological, Unco Film Festival is back with its twelfth installment of excreta exploration. Hosted by legendary mangaka Shintaro Kago, the festival displays the work of independent filmmakers… A Kite (or simply Kite to Western audiences) is a 1998 OVA anime, written and directed by Yasuomi Umetsu. Originally released as two separate episodes on VHS, all subsequent DVD… Japanese ‘erotic grotesque nonsense’, often abbreviated to ‘ero guro’ or ‘ero guro nansensu’, is a genre of art that extends to various mediums. Consequently, the genre exists as a broad… Crimson Climax is a three-part erotic yuri horror drama based on the Adult visual novel game Hotaruko by Tiger Man Project. The anime was directed by Daiitiya Otosime and Katsuma…Unco Film Festival Vol 12 – Extreme Excreta Exploration

Kite (1998) Anime Review – Film Noir Action

Japanese Erotic Grotesque Art: 5 Definitive Figures

Crimson Climax (2004) Anime Review – A Dark Tale of Human Sacrifice, BDSM, and Murderous Mannequins

Hi, I have a borderline obsession with Japanese showa-era culture with much of my free time spent either consuming or researching said culture. Apparently I’m now writing about it as well to share all the useless knowledge I have acquired after countless hours surfing the web and peeling through books and magazines.