“There is always some madness in love. But there is also always some reason in madness.” -Friedrich Nietzche

Last year, cinema fans worldwide were able to engage and appreciate the talents of director Macoto Tezuka (officially romanized as Tezka and used here to denote between father and son) thanks to Third Window Films’ restoration and release of his 1985 film The Legend of the Stardust Brothers; an incredibly fun musical that deserves a place in the pantheon of cult classics alongside Rocky Horror and Phantom of the Paradise. This year, however, we get a more modern and mature look at his craft with the release of his latest feature from 2019 Tezuka’s Barbara. The film is an adaptation of his father’s, Osamu Tezuka, infamous manga of the same title. Dealing with themes of taboo sexuality, societal scandals, and occultism, Barbara was often thought to be impossible to commit to film.

Released on what would be his 90th anniversary, it is because of this controversy that the very premise of Tezka adapting one of his father’s most unique stories stands as an incredibly intriguing concept. I feel that, due to this, it is important to lay some groundwork with a bit of background before diving fully into the film itself.

”In the lonely old park’s frozen glass two dark shadows lately passed. Their lips were slack, eyes were blurred. The words they spoke scarcely heard. In the lonely old park’s frozen glass two spectral forms invoked the past.” -Paul Verlaine

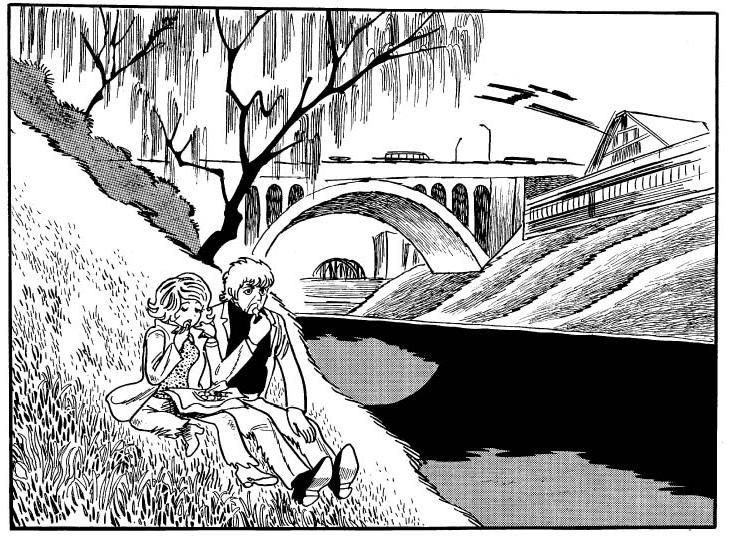

Dubbed Japan’s answer to Walt Disney and often considered the ‘Godfather of Manga and Anime’, Osamu Tezuka is responsible for creating many beloved works ranging from Astro Boy to Princess Knight and Kimba the White Lion. While his career also includes titles that have a more adult-oriented focus like Black Jack or Dororo, Barbara exists as something of an outlier in his bibliography. First serialized in 1973 within Big Comic, Barbara was billed as a follow-up to his prior work Ayako (1972-73) and finished with fifteen chapters published. The two share a theme of watching a protagonist’s descent into madness, but Ayako places a much greater focus on the horrors of war and the impact of World War II much like another Tezuka manga: Message to Adolf (1983-85).

Instead, Barbara hones in on an individual’s mentality and personal demons. Namely our protagonist Yosuke Mikura, a famous author struggling with his own success and the nature of his craft. Mikura’s stagnant life accelerates into chaos after a chance encounter with the mysterious Barbara. The story itself pulls a lot of inspiration from The Tales of Hoffman (1881), an opera created by Jacques Offenbach. Regarding the manga, Tezuka himself stated that Barbara is, “The story of a man caught between the decadent-ism of art and madness.” Digital Manga Publishing ran a successful Kickstarter to fund the printing of an English edition of the manga. This is sadly now impossible to find and any new fans hoping to dive back into the original source material will, unfortunately, join me in waiting on a future print run for the chance to add it to the shelf.

Though perhaps lesser-known worldwide than his father, Macoto Tezka is an equally accomplished storyteller through the medium of film. At just the age of 17, he won a prize for an amateur 8mm film and received praise from famous director Nagisa Oshima. In college, his career took off with the aforementioned Stardust Brothers. Since then, Tezka has gone on to create numerous other features and shorts notably adapting famous novelist Ango Sakaguchi’s Hakuchi: The Innocent and even dabbling in animation with an adaptation of one of his father’s most enduring characters, the rogue surgeon: Black Jack. In 2016, with renewed interest in the film, he was able to create the semi-sequel The New Legend of the Stardust Brothers.

All this brings us to adapting Barbara, which seems to be something of a white whale for Tezka. In the interview included on the Third Window disc, Tekza spends some time illuminating us on the complications of adapting manga to live-action and how it differs from animation projects. He also revealed that the idea to adapt Barbara began some ten years ago but was sidelined until the project could move ahead noting that things really took off once they had finally cast the leads: Mikura and Barbara. Tezka added that he felt the story of Barbara fit his style and artistic feelings, admitting that though it may be strange, he felt very close to the story.

Assisting in this effort with the screenplay is Hisako Kurosawa. While beginning her career as a broadcast journalist, she eventually transitioned her focus to screenwriting. Apprenticed to well-known playwright Haruhiko Arai, she has gone on to be very active in both television and cinema providing scripts for directors ranging from Koji Wakamatsu to Hiroshi Ando. Keen tokusatsu fans may recognize her as well having shared screenwriting duties on several seasons of Ultraman: Ginga S, X, and Orb The Origin Saga.

The final piece to the puzzle in the impressive artistry behind Tezuka’s Barbara lies with the visuals of the movie itself. The shooting is helmed by famed cinematographer Christopher Doyle who in his prolific career has worked with a wide range of directors from Gus Van Sant to M. Night Shyamalan and even Alejandro Jodorowsky. However, Doyle is probably best known for his efforts in the Hong Kong film industry and the many collaborations with legendary director Wong Kar-wai. Films like Chungking Express and In The Mood for Love have very distinct visuals and vibrant color palettes that have become something of a trademark to Doyle’s style. This same talent is on full display in Tezuka’s Barbara, so much so that it could be easy to forgive someone with no context on the movie trying to claim it is riffing heavily from the films of Wong Kar-wai visually.

”I often have this dream. Strange and penetrating. Of a woman, unknown. Whom I love, who loves me … Her eyes are the same as a statue’s gaze. And in her voice, distant, serious, mild, the tone of dear voices, those that have died.” -Paul Verlaine

As the film opens with various shots of Tokyo, particularly at night with the subtle mix of greens and blues, almost immediately you are struck with just how impressive the visuals are. Right away, fans of Wong Kar-wai are going to be able to draw parallels to his collaborations with Doyle. The second thing to really strike the viewer is the film’s score composed by Ichiko Hashimoto. Anime fans may recognize her as the composer behind classic early 2000’s mecha anime RahXephon. She has also collaborated with Tezka in the past composing the score for Hakuchi: The Innocent. While there are moments of subtle synth work and haunting melodies to back the more occult-leaning elements in the film, much of the score is filled with wild chaotic jazz pieces. The jazz-laden score gives the film some real character and meshes well with the way the film is shot to give a heavy film noir air to the story.

These noir tones are only accentuated further by the film’s characterization of the lead, Yosuke Mikura, played by Goro Inagaki. Former member of famed music group SMAP, Inagaki has had quite a successful film career, even collaborating with Takashi Miike in 13 Assassins and appearing in the anthology film The Bastard & The Beautiful World which included Sion Sono among the directors involved. As Mikura, clad in a black suit with dark sunglasses over his eyes and a confident saunter to his step, Inagaki perfectly captures the hardboiled aesthetic of a film noir lead.

Our first major scene of the film involves Mikura wandering along and happening upon Barbara near a subway station. With dirty disheveled clothes and clearly in some sort of drunken stupor, she comes across as just a random homeless person or drifter; and yet something about her catches Mikura’s interest. Barbara is played by Fumi Nikaido who shares some interesting film history in regards to Inagaki. Nikaido also collaborated with Takashi Miike in the past on 2013’s Lesson on Evil. Her first major breakthrough role was in the hard-hitting drama Himizu (2011) directed by Sion Sono. A frequent Sono collaborator, she also appeared as one of the leads in his madcap movie about filmmaking Why Don’t You Play in Hell? (2013).

Sono has a trend of casting beautiful women who then give amazing performances that portray very complex nuanced characters that go beyond being just a pretty face and Fumi Nikaido may be the pinnacle of this. There is so much powerful emotion and presence on hand in her acting that she immediately commands the screen from the second she appears. Chances are, if you’ve managed to catch her in any of her prior appearances then it is very likely that her performance was the highlight of the film. That’s why I can confidently say that she was the perfect choice to bring life to Barbara.

When I first heard about this project, I knew that the entire production would sink or swim based on whoever got selected to portray the titular character and the chemistry between her and Mikura. None of this praise is to sell short Inagaki’s performance either. Mikura is an equally complex character and I was very happy throughout the film to see both actors giving it their all and delivering exactly what Tezuka’s Barbara needed to become a great work of art.

Rather than walking through the entire plot beat by beat, I’m going to leave some discovery to your own viewing and talk a bit about the themes that really struck me in the film as well as its relationship to the original manga. This will get into spoilers for specific scenes, so if you’d like to go in completely blind, then feel free to skip to the final section to just get my overall thoughts.

Tezuka’s Barbara makes some interesting decisions in its adaptation that for me actually surpass the source material. The first thing that sticks out is simply the presentation. Tezuka has a very distinct art style. While it is certainly flawless, I have always felt that it seemed a little ill-fitting for the premise of Barbara and some of his more cartoony designs with certain characters feel in contrast to the story being told. The film comes across as a well-oiled machine with all parts tuned to nail this dark noirish tale. However, what is perhaps most notable is the absence of exposition for many of the scenes. The original manga features a lot of narration from Mikura himself explaining things. The final chapter of the manga is almost entirely exposition that involves a new character going over everything and wrapping the story up in a tight bow. To the strength of the movie, this content is avoided completely.

Mikura is an accomplished writer that has fallen into something of a rut with his career. He worries over whether the writing he has done truly has any merit to it. He struggles with an inability to find romance or intimacy with another woman despite being surrounded by many who desire him. He also worries about strange desires and ideas of sexual deviancy that well up inside his mind from time to time. The manga tells us all this upfront. The film subtly reveals the same information to us through Inagaki’s performance and his interactions with others in a much more layered fashion.

Another early scene sees Mikura arrive at a party to celebrate the success of a colleague: Hiroyuki Yotsuya. Yotsuya is portrayed by Kiyohiko Shibukawa who recently gave an incredible performance as one of the leads in Toshiaki Toyoda’s The Day of Destruction (2020), reviewed here by me. Here he plays only a supporting role in the story, but as Yotsuya works well being a sort of foil to Mikura. Arriving at the party, Mikura is rushed by women desiring to speak with him eagerly and we see his casual disinterest. Even the women closest to him, his agent Kanako (Shizuka Ishibashi), and a presumed girlfriend Shigako (Minami) get little more than cold disinterest. In the manga, again, things are a bit more overt as clearly the fathers of both women hope to marry their daughter off to the successful Mikura. Here, while Shigako’s story remains mostly unchanged, we are instead shown a more silent, almost motherly devotion from Kanako. Unfortunately, they only receive casual disregard for their affection.

More interesting, however, is the speech being given in honor of Yotsuya. Like the time-honored tradition of horror films doling out their theme through a classroom lecture, the words being spoken seem pointedly aimed at Mikura. The speaker talks about how for many writers that eventually see their fame go into a decline and the sales start dropping, they devolve into writing cheap erotic stories with little value just to get their numbers to go back up. While the speech is merely talking in generalities, it seems to mirror and underscore Mikura’s own situation.

During their first meeting, Mikura invites Barbara back to his apartment. She reads a page of his latest work and it appears to be exactly the sort of poorly made cheap erotic story that the speaker at the party refers to. Barbara states that while he does have talent, she thinks little of his work and that it is far too clean. It’s clearly a sore spot for Mikura as her teasing prompts him to throw her out in a rage. However, his fascination with Barbara ensures that they will meet again.

Twice, she saves him from very surreal encounters that turn quite sinister. First, from a seductive store clerk. This is an incredibly jarring scene in the film that’s sure to grab some interest from horror fans. What begins as a hookup in the dressing room spirals out of control as the woman asks Mikura to hit her and proceeds to talk about how worthless his novels are. But as she becomes just a bit too aggressive, Barbara arrives on the scene to save the day by decapitating the woman. It’s sudden and out of left field, but plays out so well. As Barbara continues to disassemble the woman we are quickly shown that it is actually a mannequin prompting her to tease Mikura over being some sort of fetishist.

The second incident is even more mystifying. While visiting Shigako and her father, who hopes to draft the talented writer in as support for his political ambitions, Mikura winds up excusing himself to the bathroom to escape what he feels is an unpleasant and overwhelming situation. On the way, he meets a mysterious alluring woman and departs with her into the woods. Their sudden tryst also spirals into chaos as the woman seemingly turns into a vampire and bites Mikura. Once again, Barbara is there to save the day but we get an even more shocking revelation. The woman Barbara has bludgeoned to death turns out to be Shigako’s pet dog. In the manga, these same events happen but they have a much more powerful edge in the film.

By contrast, we are told very early on in the manga through Mikura’s narration that his mind sometimes becomes filled with strange sexual desires. In the film, we are dealing with subtlety and piecing together things as the story progresses. This sort of slow revelation reinforces the noir tone as well. It’s safe to say that Mikura is a pretty messed-up guy. Following his story is interesting in that he comes across as completely charismatic and it’s hard not to want to root for him. Yet, he is clearly not a very good person. For all his insecurity and artistic ambition, he’s also unbearably misogynistic, seeing women as either objects for his own sexual gratification at best or a bothersome distraction at worst. But then there is Barbara.

As his obsession with Barbara grows, Yotsuya debates with Mikura a bit about the women in his life, even pointing out Kanako’s support and devotion to him as his agent which goes far beyond simple professionalism. Mikura casually dismisses this assertion by stating that she only hangs around him because of the money. Rarely, we are given a look at some of Mikura’s actual writing with some choice gems like, “There is no demon as bothersome as a bad woman. There is no demon as pathetic as a good woman.” During the middle of the film, we find Mikura debating the nature of novels and his art. To which he states that art is a goddess out of his reach. In his own words, “Beautiful, capricious, a man’s downfall.” These lines probably say way more about Mikura than it does anything else.

And yet, to Mikura, Barbara offers something more. Despite her crass attitude, there is something complex and enchanting about her. Her straightforwardness seems refreshing from the tightly structured world Mikura moves through as a famous novelist and her hippie-like free spirit appears to offer a different way of looking at the world. His time spent with her inspires him to write more seriously and he begins to look at her as a muse that has chosen to offer her blessing upon him. When the two finally make love it is an incredibly passionate moment. While there’s plenty of nudity on display, the shot and framing of the scene manage to impart a lot of emotion without ever being exceedingly graphic. It draws to mind the very best of the more artistic side of Nikkatsu’s Roman Porno series. This is not simply sex, but two people completely lost in rapture with one another.

The next morning, Barbara offers Mikura an apple, and this incidental scene, which summons to mind the forbidden fruit in the Book of Genesis, launches the story in a new direction. From this point forward their lovemaking intensifies, underscored by a darker tone within the film’s score. Mikura begins to withdraw from society and the few people close to him devoting all his time towards Barbara and writing. As things escalate more strangeness begins to circulate around the couple. Barbara drags Mikura to a seedy bar that functions more like a sex club. It’s a great scene cast in beautiful hues of color and an amazing gothic song being performed by a nameless musician. The musician is portrayed by Issay who played villain Kaworu in Tezka’s Stardust Brothers which makes for a fun cameo. The musician recognizes and accosts Barbara while warning Mikura that he will suffer the same fate as him.

Meanwhile, the occult elements begin to take center stage. Mikura discovers strange voodoo dolls around his apartment. Those closest to him begin to die in unexplained freak accidents. As the couple considers marriage, Barbara takes him to meet her mother: a fortune-teller named Mnemosyne (Eri Watanabe). Mythology buffs will note that Mnemosyne is the name of a Greek goddess who birthed the nine Muses which were thought to offer inspiration to poets and other creatives. Mnemosyne requires Mikura to sign a contract in blood like some sort of Faustian bargain. Their wedding ceremony takes place as a sort of black mass complete with cultists chanting and being staged in a lavish mansion that feels like it could be owned by the secret society in Eyes Wide Shut. Mikura’s uneasiness in the proceedings and the rapid chaotic escalation reminded me of Sergio Martino’s All The Colors of the Dark and its overwhelmingly paced ritual scenes.

This is another area where the film supersedes the manga, in my opinion. Through exposition, the idea that Mnemosyne and Barbara are some sort of supernatural presence is plainly laid out and we get a lot of extra details about the cult that surrounds them. The film, however, dwells in the abstract and leaves it up to us to draw our own conclusion. This makes these segments not only more sinister but also more compelling. We are never really too sure throughout the film what’s really happening and what is perhaps just the projection of Mikura’s twisted mind. Even when his activity with the cult gets exposed, threatening to ruin his career, the details are left vague enough that you’re not too sure what society has been told compared to what Mikura knew and experienced.

And that’s the true strength in the film’s presentation of the material. During the mannequin scene, if her existence is Mikura’s imagination then her insults regarding his work represent the projection of his own insecurities. Her desire to be abused by him, a reflection of his own repressed sadistic predilection. In the manga, Mikura explicitly tells us that his mind sometimes fills with these deviant sexual desires. The film brings us to understand this fact in a much more intimate way. Paralleling his descent into madness and ruin during the final act, some of his decisions that go into a much darker place, involving ne***philia and cannibalism, come as way more of a gut-punch to the viewer when Mikura hasn’t already set it up through narration earlier. We see the true descent of someone lost in obsession down into their own personal hell.

But regarding Mikura projecting his mental state, you can extrapolate this concept to many of the events in the film; including Barbara. Throughout the movie, we only see Barbara alone and interacting with Mikura or characters directly related to her like Mnemosyne. When other characters come to visit him, she always happens to be out. The closest brush to any other interaction comes in a scene where Kanako is checking up on Mikura and Barbara intentionally hides out of sight behind the kitchen counter. Yotsuya suspects that Mikura’s sudden change in behavior is due to falling for some woman, but ultimately none of his acquaintances ever meet or learn about Barbara. What we can see of the scandal regarding the cult simply focuses on the cult itself with no mention of her.

So with regard to the film’s presentation is Barbara some divine muse? A supernatural force that drifts in and out of the lives of artists balancing them on the razor’s edge between the chance for success or ruin? Or is she perhaps another projection of Mikura himself? A perfect woman, in his eyes, that saves him from all the things that he perceives to be problematic while encouraging and reassuring his own desires. We’re never given a complete look at Mikura’s life enough to fully grasp the state we find him in at the start of the movie, but it’s all the more intriguing for it. Any way you want to interpret it makes for some interesting thoughts and discussion.

“Love is the greatest form of art, created from blood and bones.” -Junichiro Tanizaki

There are so many threads and interesting connections to other works that I think if you have even a passing interest in any of these ties then this is a must-watch movie.

Osamu Tezuka fans need to see it for a grand slam of an adaptation for one of the master’s most curious manga. Wong Kar-wai fans need to see it just to soak up more of Christopher Doyle’s lavish visuals that have helped define so many amazing films. Fans of more transgressive in-your-face Japanese directors like Sion Sono, Toshiaki Toyoda, and Takashi Miike need to see it because it meshes so damn well tonally that it could easily play among them in a marathon effortlessly. Literature nerds need to see it and geek out over all the choice quotes and references to other works. Gamers that enjoyed Atlus’ Catherine with its story of a man torn between the grounded but uncertain reality of life with his fiancé and the passion of a surreal supernatural temptress that offers to fulfill repressed desires should see it for some interesting thematic links. General fans of manga and anime should see it just to be proven that sometimes a live-action adaptation can get things totally right. All Creatives, regardless of their artistic medium, need to see it for a haunting and sobering tale of a reality that any of us could fall into without care.

In many ways, with its chaotic jazz-fueled score, neo-noir style, and a plot that eschews the over-exposition of its source material to instead dwell cautiously in subtlety, I think it can be argued that Tezuka’s Barbara actually improves upon the original manga. It’s an amazing achievement executed by the sheer talent and dedication of every party involved in its production. It is my sincerest hope that this will be a springboard for Macoto Tezka towards more projects in the future and greater recognition of his work worldwide.

The DVD/Blu-ray release from Third Window Films is out now and packed full of extras including behind-the-scenes footage, deleted scenes, an alternate ending, and a plethora of interviews with the cast and crew. I think the interview with Tezka is the highlight. If you enjoy the film at all, listening to him talk through the inception of the project and his process is quite illuminating. Furthermore, the discs are All-Region coded ensuring that you’ll be able to conveniently check it out regardless of where you are in the world.

While it may have been originally released in 2019, with Tezuka’s Barbara only seeing its wide release now I have to say that this is easily my film of the year for 2021. It doesn’t matter what else the latter half of the year has to offer, nothing is going to touch the artistic high that this film gives me. Like Mikura, I think I have become enchanted by Barbara. Awash in inspiration from this wonderful movie, all I can do is write in the hopes of capturing something transient and divine, passing the word along to guide others to discover and appreciate this film.

“A woman like the city’s excrement from the millions of people that it consumed and digested. That was Barbara.” -Yosuke Mikura

More from Third Window Films:

Electric Dragon 80.000 V (2001) Film Review – New Kids on the Shock

Electric Dragon 80.000V is a 2001 experimental sci-fi fantasy, written and directed by the legendary Gakuryû Ishii (previously known as Sogo Ishii). Most notable for films such as Crazy Thunder…

Violence Voyager (2018) Film Review: A Unique Vision of Madness From UJICHA

Japanese artistUjicha has been garnering a cult following, and even before watching this movie, I was aware of the name through buzz coming from the film fests. However, I had…

Fish Story (2009) Film Review: An Emotional Masterpiece Highlighting the Importance of Music

Straight Outta Kanto here reeling you in with a Third Window Films movie that I can guarantee you won’t be the one who got away… The dictionary defines Fish Story…

One Cut of the Dead Spin-off: In Hollywood (2019) Film Review

In 2017, a little movie from Japan called One Cut of the Dead arrived on the scene and took everyone by surprise. Being a micro-budget movie that was only made…

Film Review: Melancholic (2019) – Seiji Tanaka’s Millennial Thriller

If ever there was a personification of “It’s not the Destination, it’s the Journey”, it’s Seiji Tanaka’s 2018 Millennial thriller Melancholic. Released recently in dual format by the pioneeringThird Window…

Film Spotlight: Confessions (Kokuhaku) [2010]

Confessions (Kokuhaku in Japan) is a 2010 revenge thriller based on Kanae Minato’s critically acclaimed debut novel. From director Tetsuya Nakashima who also produced the visually bubbly ‘Kamikaze Girls‘ and…

Dustin is a potentially overqualified office worker who has a lifelong love and fascination with Japan and all things Horror. With a bachelor’s in English Literature and a master’s in Library Science, he devotes way too much time to researching and thinking critically about the media he enjoys. When not celebrating trashy horror films, anime, and idol music, he can be found raving about all things genre cinema as a co-host on Genre Exposure: A Film Podcast or indulging a passion for storytelling through tabletop roleplaying games.

![Film Spotlight: Confessions (Kokuhaku) [2010]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/confessions-header-365x180.jpg)