True crime has always mustered a strong, morbid curiosity from society. From the events unfolding on live news feeds to popular podcasts and video essays, this macabre fascination seems to have been around for as long as crime itself. However, it’s safe to say that the most popular way of exploring these heinous acts is through their depiction in film, especially when it comes to Asian cinema.

In this list, you will find a diverse array of cinematic masterpieces that draw inspiration from real-life criminal cases, offering a unique lens through which to explore the complexities of the human psyche and the often-untold stories that lurk behind the headlines. From gripping courtroom dramas to suspenseful investigative thrillers, these films not only entertain but also shed light on the socio-cultural intricacies that underpin the criminal underworld.

List Contents:

- The Untold Story (1993)

- The Forest of Love (2017)

- Dr Lamb (1992)

- Nobody Knows (2004)

- Concrete-Encased High School Girl Murder Case: Broken Seventeen-Year-Olds (1995)

- Itaewon salinsageon (2009)

- Vengeance is Mine (1979)

- Violated Angels (1967)

- I am Ichihashi: Journal of a Murder (2013)

- Rain of Light (2001)

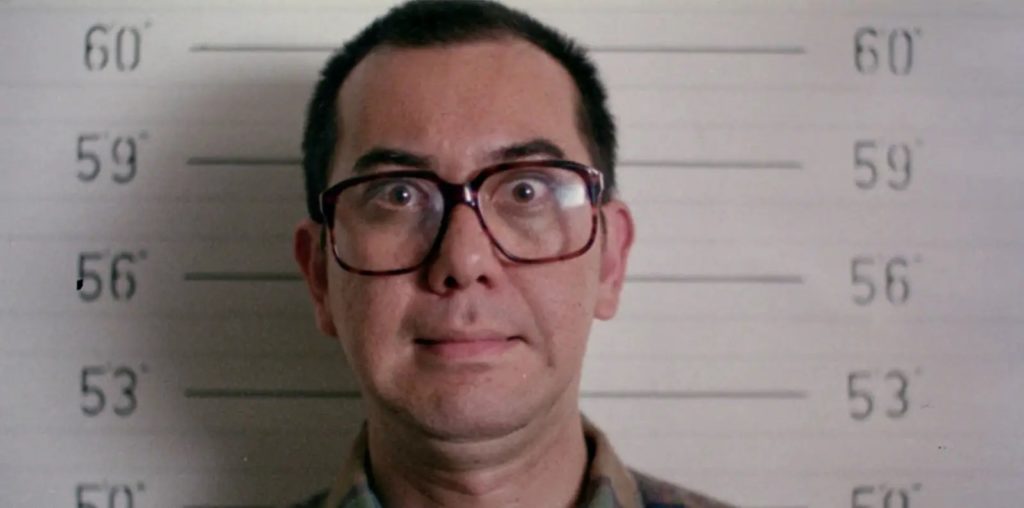

The Untold Story (1993)

The Untold Story is a 1993 Hong Kong CAT III exploitation horror, written by Wing-Kin Lau and Kam-Fai Law, and directed by Danny Lee and Herman Yau. Macau cops begin to suspect a man running a pork buns restaurant of murder, after tracing the origin of a case full of chopped-up human remains that washed ashore, which leads them to him.

Detailing the events of the Eight Immortals Restaurant murders, The Untold Story tells the story of Huang Zhiheng, a Chinese mainlander who emigrated to Hong Kong before fleeing to escape a murder charge in 1973. After spending years on the run from this crime in Macau, he proceeded to brutally murder a family of ten over a gambling debt, but, instead of fleeing, he dismembered their corpses, dumping them in the ocean, and continued to run the family’s restaurant for over a month. As he was a close acquaintance of the family and held the restaurant’s title, the staff and patrons believed Zhiheng’s fictional tale of purchasing the business and the family’s emigration back to China. However, with the bodies being discovered washed ashore and family from the mainland enquiring about their disappearance, it wasn’t long before the police grew suspicious of Zhiheng. After some investigation, Zhiheng was captured by the Police whilst trying to escape to mainland China and arrested.

Whilst the film somewhat embellishes this crime, playing on the rumour that Zhiheng sold the flesh of his victims from the restaurant, it provides a disturbingly grotesque peek into the monstrous acts he did commit—holding very little back when it comes to its unhindered visualisation. With several grisly murders shown within the first few minutes, the film undoubtedly earns its CAT III rating earnestly.

The Forest of Love (2019)

The Forest of Love is 2019 a Japanese crime-thriller film, written and directed by Sion Sono. It tells the story of Joe Murata, a charismatic and manipulative con artist named who forms a disturbing and unconventional relationship with the sheltered Mitsuko and her former high school classmate, the traumatized Taeko.

Joe Murata’s manipulative tactics escalate from charm to violence, ensnaring not only Mitsuko and Taeko but also their families and friends in his criminal web. As the plot progresses, each character descends further into despair under Murata’s influence. His charisma blinds them, leading them down a dark path they never anticipated. The film masterfully portrays how seemingly likable characters can be twisted into heinous murderers, all driven by Murata’s depraved desires. This disturbing exploration of human vulnerability and, more importantly, how a cult does not need to be a religious institution. Sometimes, it can start in your own family if a malicious leader sees the opportunity.

Despite being somewhat of a loose adaptation, the Forest of Love takes most of its inspiration in Futoshi Matsunaga, a convicted Japanese serial killer. Along with his lover, Junko Ogata, he committed a series of murders in Japan between 1996 and 1998. His modus operandi was very similar to his film counterpart, since he pushed his followers -most of them members of the Ogata family- to torture and murder each other, including children as young as 5 years old.

Dr Lamb (1992)

Dr. Lamb is a 1992 Hong Kong CAT III crime thriller, Written by Kam-Fai Law and directed by Danny Lee and Billy Tang. An abnormal taxi driver lusts for blood every rainy night, and several young women are killed as a result. The murderer, Laiu, likes to take photos of the victim’s dismembered bodies as momentos.

Based on the crimes of one of Hong Kong’s most notorious serial killers, Dr. Lamb recounts the heinous acts of Lam Kor-wan, who, whilst working as a taxi driver, abducted, strangled, and mutilated the corpses of four young women in Hong Kong between Feburary-July 1982. After these unsuspecting victims entered Lam Kor-wan’s taxi, he would drive to a secluded area, handcuff them, strangle them with electrical wire, and take the bodies back to his family home where he would remove the sexual organs to preserve in rice wine. He would proceed to dismember the rest of the corpse, disposing of the remains by dumping them in various locations.

The police were only made aware of the maniacal taxi driver after he tried to develop photos of a mutilated corpse at a Kodak shop. Once the manager had contacted the police, they swiftly descended on the shop to await their assailant’s return where he was swiftly arrested. Upon searching his family home, the police uncovered overwhelming evidence in the form of the preserved sexual organs, a wealth of photographs of the victims as well as a number of videotapes that depicted the dismemberment of all four victims, the cannibalisation of his third victim, necrophilic acts with his fourth victim.

After a lengthy three-week trial, Lam Kor-wan was found guilty of the murder of Chan Fung-lan (22), Chan Wan-kit (31), Leung Sau-wan (29), and Leung Wai-sum (17), being sentenced to death by hanging. However, after a mercy plea was entered by Wan, his sentence was reduced to life, which he is still serving.

Unlike most CAT III films that embellish the original crimes to sensationalise the acts or provide more gruesome visuals to shock audiences, Dr Lamb is a relatively realistic portrayal of the crimes committed by Wan. Despite this, there is still a slight inkling of fiction to Wan’s early life that may or may not be true to explain away the nature of his crimes.

Nobody Knows (2004)

Nobody Knows is a 2004 Japanese drama, written and directed by Hirokazu Kore-eda. The film tells the story of four siblings: Akira, Kyōko, Shigeru, and Yuki, aged between twelve to five years old, they find themselves abandoned in their apartment by their irresponsible mother. Neglected and deprived of education, they are often left to fend for themselves while they try to remain invisible to their neighbors due to their illegal occupancy of their apartment.

As time passes, their mother’s infrequent visits dwindle to nothing when she becomes entangled with a new lover. The burden of responsibility falls heavily on Akira, the eldest sibling, who attempts to maintain a semblance of normalcy within their makeshift home. However, the harsh realities of their situation quickly become apparent, revealing the limitations of a twelve-year-old with limited education and money. When Akira grows frustrated and starts to neglect his siblings, the story reaches a tragic climax, one that is sure to shatter the heart of even the most cynical viewer.

Similar to Kore-eda’s portrayal, four siblings were left unattended for months by their mother, who chose to live with her lover instead. However, despite the film’s visceral impact, the director chose to gloss over the grittier details of the case, crafting a narrative that, while powerful, only hints at the full extent of the tragedy. In reality, the children’s neglect was even more severe, leading to a tragic outcome that involved the intervention of a juvenile court due to the older brother’s involvement. Perhaps even more frustratingly, the mother regained custody of two of her children after serving only a three-year sentence for child abandonment.

Concrete-Encased High School Girl Murder Case: Broken Seventeen-Year-Olds (1995)

Concrete-Encased High School Girl Murder Case: Broken Seventeen-Year-Olds is a 1995 Japanese exploitation horror film, written and directed by Katsuya Matsumura with additional writing from Takafumi Ohta. A 17-year-old boy, Jo Kamisaku, and three other boys abduct a high school girl Junko Furuta.

Pertaining to the incredibly woeful case of Junko Furuta, a young high school girl who endured 40 days of hellish torment at the hands of a group of sadistic youths. While wandering the city of Misato to commit robbery and sexual assault, Hiroshi Miyano and Shinji Minato witnessed Junko riding home from work. After Miyano gave chase, and knocked her off her bike and fled the scene, Minato approached the young girl and deceptively offered to escort her home safely. However, after gaining her trust, he proceeded to abduct her, rape her multiple times, and threaten to kill her if she spoke out; later calling Minato as well as some other friends, Jō Ogura and Yasushi Watanabe, to brag to them about the acts just committed.

It was Ogura who suggested that they keep the girl in captivity to allow others to sexually abuse her, and after convincing the poor girl that Yakuza would kill her parents if she escaped—keeping her captive at Minato’s parent’s house. What happened in the house over the next 40 days is considered some of the worst crimes perpetrated by underage persons in Post-war Japan, suffering a torrent of physical, mental, and sexual abuse at the hands of the four teenagers as well as many others they invited to join in their sick games. Beginning on 25 November 1988, Junko would eventually succumb to the savagery inflicted upon her on 4 January 1989 after an incredibly savage beating from the teens that reportedly lasted two hours.

After her death, the group wrapped Junko’s body in blankets and placed her in a sports bag, placed in a 55-gallon drum and filled it with concrete—disposing of the drum in a cement truck in Kyoto. Unfortunately, the group seemingly got away with this crime, with her body not being found by the police and only being listed as missing by her parents. Junko would only receive justice after Miyano and Ogura were arrested for the gang rape of another 17-year-old, surprising police by confessing to her murder when they had no idea she was, in fact, dead. After searching the area described by the pair, they recovered the drum and identified Junko’s body through fingerprints, bringing an end to one of the most brutal counts of abduction in modern history. Upon being prosecuted for “committing bodily injury that resulted in death,” rather than murder, the group received sentences varying drastically in length. Miyano received 17 years in prison, though he appealed his sentence but was rejected and had 3 additional years added. Watanabe received only 3-4 years in prison but had an additional year added. Ogura received 8 years in juvenile prison, Minato received a 4-6 year sentence but was later resentenced to 5-9 years in prison. Furuta’s parents later launched a civil suit against the parents of Minato, whose house the abuse took place in, and was rewarded 50 million yen to be paid by Minato’s mother.

An incredibly exploitative piece of Tabloid horror, was one of the first films based on the odious torments Junko had to endure—made only 6 years after her death. Poised as a crime re-enactment hosted by a narrator, the film goes into a disturbing level of detail acting out these crimes—taken from details confessed by the perpetrators. While Concrete-Encased High School Girl Murder Case: Broken Seventeen-Year-Olds may be one of the most true-to-life representations of Junko’s fate, it is delivered in incredibly poor taste that sensationalises these crimes rather than document them. That being said, the film is still a brash example of Japanese exploitation cinema and its disregard for decency.

Itaewon Salinsageon (2009)

Itaewon Salinsageon is a 2009 South Korean mystery thriller, written by Young-soo Ahn and Lee Maeng-yoo, and directed by Ki-Seon Hong. Two Korean-American teenagers are brought for questioning and are charged with murder of a college student, possession of a lethal weapon, and withholding evidence. However, with neither of the teens showing remorse for their heinous crimes and blaming each other for the killing, the police have difficulty finding the truth of the event.

Detailing the events of the Itaewon Burger King Murder in Seoul, South Korea, where two Korean-American teenagers, Edward Lee and Arthur Patterson, brutally stabbed Korean college student, Jo Jung-Pil, to death in the establishment’s bathroom on April 3, 1997. The pair used a knife to stab Jo Jung-Pil 9 times in the carotid artery, leaving him to bleed out from the injury. After an anonymous tip, the pair was arrested, however, what should have been a simple open/shut case turned into one of the most baffling legal cases in the country’s history.

As Arthur’s father was an ex-American military stationed in South Korea, the case was handled by both Army CID and South Korean investigators. While the Army CID had collected what was considered to be enough evidence to convict, the South Korean investigator’s inability to speak English—slowed the investigation to a crawl at times. Additionally, as both Arthur and Edward claimed the other was the one to commit the stabbing, it was difficult to pinpoint where responsibility lay when trying to charge the pair. While, at first, Edward was tried and convicted for the killing, with Arthur only receiving a charge with possession of a weapon. However, Edward’s conviction would soon be acquitted by the Supreme Court of South Korea for insufficient evidence. Arthur’s convicted for the possession of a weapon charge but was soon released from Prison after his sentence was stopped, soon leaving the country to travel back to America, further complicating the investigation.

After Itaewon Salinsageon (2009) was released and reignited interest in the case, and, due to public demand, forced the Department of Justice to cast another judgment on the case—petitioning for the extradition of Arthur on December 15, 2009. As there was no limitation of travel placed on the teen after his release, and if they could not prove a case of ‘in a foreign country to escape criminal actions’, the statute of limitation of the crime was closing in exponentially, expiring in April 2012. Thus, on December 22, 2011, Arthur Patterson was once again prosecuted by South Korea, and after a lengthy back and forth between prosecutors and American attorneys, in October 2012, the U.S. federal court in Los Angeles ruled for Patterson to be extradited to South Korea. However, after some petitioning from Arthur, his extradition was delayed slightly but was finally charged for the crime of murdering Jo Jung-Pil in January 2016, receiving 20 years in prison. Although US courts agreed that Edward instructed the murder, the possibility of indictment remained unclear until the statute of limitation for the crime was up.

Being a large part of why the conviction was achieved, Itaewon Salinsageon is an indisputably realistic depiction of the failing of the South Korean Justice system. Mostly focusing on the complicated legal proceedings that surrounded the case, it could certainly be argued that, if not for the film, Jo Jung-Pil may never have received justice for his senseless murder.

Vengence is Mine (1979)

Vengeance is Mine is a Japanese 1979 crime drama, written by Masaru Baba and Shunsaku Ikehata, and directed by Shôhei Imamura. The film is based on the book of the same name by Ryūzō Saki. Iwao Enokizu is a middle-aged man who has an unexplainable urge to commit insane and violent murders. Eventually, he is chased by the police all over Japan, but somehow he always manages to escape. He meets a woman who runs a brothel. They love each other but how long can they be together?

Based on the five murders committed by Akira Nishiguchi, as well as the national manhunt that led to his arrest, Vengeance is Mine is a very detailed depiction of the spree of murders committed by Nishiguchi. Having numerous priors for robbery, extortion, and fraud, Nishiguchi was fairly well-known to the police before his murder spree.

The first set of murders occurred in October 1963, when Nishiguchi learned that Ikuo Murata, an employee for the Japan Tobacco and Salt Public Corporation, was using Nishiguchi’s employers’ delivery vehicles to transport large sums of money along with tobacco products. After Nishiguchi approached Murata to offer to aid him in his deliveries, the pair, driven by another man, Goro Mori, drove out to an isolated mountain road in Fukuoka Prefecture, where Nishiguchi proceeded to beat Murata to death with a hammer and fatally stab Mori—abandoning the bodies and vehicle and making off with around 260,000 yen. However, the following day, he was made aware that the police had already linked him to his vicious crimes and a manhunt was well underway.

After trying to escape the police’s attention by sending them a fake suicide letter, Nishiguchi spent the next few days traveling between Kansai and Chūbu but eventually rented a room in Shizuoka from Yuki Fujimi, claiming to be a professor from Kyoto University. Having fallen for his lies hook, line, and sinker, Yuki began to develop feelings for the faux-professor and eventually invited Nishiguchi to her room to stay the night. However, due to the authorities on his tail, Nishiguchi would continue to hop from place to place all over Japan in an attempt to evade capture—defrauding anyone he could along the way. Upon returning to the apartment a few weeks later, Yuki had arranged that she would host Nishiguchi in her apartment. Unfortunately, after several days, Nishiguchi proceeded to strangle Yuki and her mother, Harue, who also lived with her daughter, to death with a length of rope and proceeded to pawn all of their possessions for cash—making off with around 140,000 yen. When their bodies were discovered around a week after the killing, the police, once again, linked the crimes back to Nishiguchi and vowed to increase the scale of the hunt for this vicious killer.

Despite this more conscientious search for the wanted criminal, Nishiguchi successfully evaded capture, leaving a trail of fraud and extortion in his wake. Upon arriving in Tokyo, Nishiguchi, who had been impersonating a lawyer to defraud people, happened to come across Umematsu Kamiyoshi, an 81-year-old lawyer and member of the Tokyo Bar Association. After assuming the gentleman’s wealth, Nishiguchi auspiciously convinced Kamiyoshi that he could offer his legal aid to a lawsuit he was working on and was invited back to Kamiyoshi’s residence. Whilst there, Nishiguchi strangled the man to death with a necktie, ransacking the apartment and making off with his lawyer’s badge, some valuables, and around 140,000 yen.

Immediately fleeing Tokyo to Kumamoto, Nishiguchi introduced himself to Tairyu Furukawa, a Buddhist priest who was campaigning for the release of death row prisoner Sakae Menda, whom Nishiguchi had met whilst in prison. Nishiguchi convinced Furukawa that he was a lawyer interested in assisting with Menda’s case. However, after Nishiguchi was taken back to his house and introduced to his family, Ruriko, aged 10, instantly recognised their guest as the criminal from the slew of wanted posters plastered all over Japan by the authorities. Though Furukawa did not believe his daughter at first, Nishiguchi’s rudimentary knowledge of law and distinctive moles soon confirmed his daughter’s suspicions were correct, offering the killer a room for the night as to avoid him evading capture—where he had his wife alert the police and Nishiguchi was apprehended in the early hours of the morning.

Upon his capture, Nishiguchi confessed outright to all of his crimes committed all over Japan and, after a year-long trial, was convicted for all five murders, along with innumerable fraud and extortion charges, and was sentenced to death by hanging on 23 December 1964. Nishiguchi’s defense launched an appeal that the defendant was mentally unwell when the crimes were committed but was unsuccessful. The execution was carried out at Fukuoka Detention House on 11 December 1970.

Whilst certain details have been changed, such as the killer’s/victims’ names being changed, Vengeance is Mine is an incredibly realistic portrayal of both the vicious crimes committed and the extended manhunt spread to all corners of Japan to find the heinous killer. The visual savagery displayed, along with the translation of Nishiguchi’s callousness presents an incredibly close representation to the actual events that occurred.

Violated Angels (1967)

Violated Angels is a 1967 Japanese horror thriller Pinku, written and directed by Kôji Wakamatsu with additional writing from Masao Adachi, Juro Kara, and Haruno Yamashita. A young man breaks into a nurse’s rooming house and one-by-one kills off nurses.

Unlike the previous entries, Violated Angels is based on a crime committed outside of Asia. The film chronicles the crimes of American spree killer, Richard Speck, who, on the night of July 13-14, 1966, committed one of the most infamous and brutal crimes in American history. Speck, a drifter, and ex-convict, broke into a townhouse located at 2319 East 100th Street in Chicago. This townhouse served as a dormitory for student nurses who were working at nearby South Chicago Community Hospital.

Armed with a knife, Speck entered the townhouse, which housed several student nurses. The victims included Gloria Davy, Patricia Matusek, Nina Schmale, Suzanne Farris, Mary Ann Jordan, Merlita Gargullo, Valentina Pasion, and Pamela Wilkening. The young women were taken by surprise as Speck rounded them up and began his horrific spree of violence.

Over several hours, Speck subjected the nurses to brutal acts of torture, sexual assault, and murder. He separated them into different rooms, tying them up and threatening them with violence. The nurses were systematically assaulted and, tragically, all eight of them lost their lives that night.

Corazon Amurao, the only survivor of Speck’s rampage, managed to hide under a bed during the ordeal. She later provided crucial testimony about the events that unfolded that night. Amurao identified Speck as the perpetrator and described the horrific acts she witnessed.

Speck’s crime shocked the nation, not only due to its sheer brutality but also because it highlighted the vulnerability of young women living in communal settings. The gruesome details of the crime, including the sexual assault and murder of eight innocent nurses, horrified the public and intensified the fear of random violence.

After a nationwide manhunt, Richard Speck was arrested on July 17, 1966, in a flophouse in Chicago. He was charged with multiple counts of murder, rape, and other crimes. In 1967, Speck stood trial, and despite attempts by his defense to argue that he was legally insane, he was found guilty.

Initially sentenced to death, Speck’s sentence was later commuted to life in prison after the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated the death penalty in 1972. He spent the rest of his life incarcerated, largely isolated from other prisoners due to the heinous nature of his crimes. Richard Speck died of a heart attack in prison on December 5, 1991, bringing an end to the life of a man responsible for one of the most chilling and unforgettable crime sprees in American history.

Rather than a standard retelling of these despicable crimes, director Kôji Wakamatsu provides an experimental, avant-garde experience that takes creative liberties to explore different themes and create a unique cinematic performance rather than providing a documentary-like account of the crimes. Focusing on themes of societal and political issues of the time, such as the Vietnam War and student activism, the film has a strong fixation on the psychological and emotional aspects of this tale rather than graphic violence.

I am Ichihashi: Journal of a Murder (2013)

I am Ichihashi: Journal of a Murder is a 2013 Japanese crime drama, written, directed, and starring Dean Fujioka. The film is based on the autobiography Until I Was Arrested by Tatsuya Ichihashi. Tatsuya Ichihashi became a notorious and wanted fugitive criminal after murdering Lindsay Ann Hawker who had moved to Japan where she was teaching English as a second language. Ichihashi has undergone plastic surgery, become unrecognizable, and eluded the manhunt for him.

The murder of Lindsay Ann Hawker took place in Tokyo, Japan, in March 2007. Lindsay Hawker was a 22-year-old British teacher who had been living and working in Japan. The case gained international attention due to the brutality of the crime and the subsequent manhunt for the suspect.

Lindsay had been teaching English in Japan and was last seen alive on March 25, 2007, after giving a private English lesson to Tatsuya Ichihashi, a 28-year-old Japanese man. Her body was discovered buried in a sand-filled bathtub on the balcony of Ichihashi’s apartment in Ichikawa, a suburb of Tokyo, on March 27, 2007.

The events leading up to Lindsay’s murder began when Ichihashi contacted her for English lessons. Lindsay agreed to meet him at a coffee shop in Tokyo on March 25, 2007. Surveillance footage from the coffee shop showed the two leaving together. Lindsay was reported missing when she failed to return home that evening.

A massive manhunt ensued, and Ichihashi quickly became the prime suspect. He managed to evade the police and went on the run for over two years, during which time he underwent extensive cosmetic surgery to alter his appearance. Despite being one of the most wanted fugitives in Japan, Ichihashi successfully avoided capture.

In November 2009, Ichihashi was finally apprehended at a ferry terminal in Osaka, where he was attempting to board a ferry to the southern Japanese island of Okinawa. He was recognized by a passerby who had seen his wanted poster.

During the trial, Ichihashi admitted to causing Lindsay’s death but claimed that it was unintentional. He asserted that he had asked her to help him study English, and when she entered his apartment, he tried to fulfill his fantasy of having consensual sex with her. When she resisted, a struggle ensued, leading to her death. Ichihashi claimed that he panicked and decided to hide her body.

In July 2011, Tatsuya Ichihashi was found guilty of Lindsay Hawker’s rape and murder and was sentenced to life in prison. The trial brought closure to Lindsay’s family, who had endured a prolonged and emotionally challenging period since her disappearance.

Being based on the autobiographical account of the killer’s actions, the film follows the events of the proceeding fugitivity of Ichihashi rather closely. However, director Dean Fujioka adopts a narrative style that delves into Ichihashi’s perspective, exploring his thoughts and emotions around the murder itself rather than just reiterating the events of the book—taking artistic freedom to tell a dramatic and psychological story from Ichihashi’s point of view.

Rain of Light (2001)

Rain of Light (Hikari no ame) is a 2001 Japanese documentary-styled crime drama, written by Takeshi Aoshima and Wahei Tatematsu, and directed by Banmei Takahashi. An extreme faction of the Students Allied Red Army is holed up in a mountainous cabin in the dead of winter. By the time the police finally caught up with them, it was discovered that they had murderously turned upon themselves in a bizarre extension of their radical philosophy.

Being based on the infamous Asama-Sanso Incident of 1972, a notable hostage crisis involving the Japanese Red Army, a militant organization formed in the late 1960s, with its roots in the student protest movements of the time and radical left-wing group. The incident unfolded at the Asama Sanso, a mountain lodge near Karuizawa in Nagano Prefecture, Japan.

On February 19, 1972, nine members of the JRA, armed with firearms and explosives, stormed the Asama Sanso lodge, which was owned by the family of the famous film actor Yujiro Ishihara. The lodge was chosen strategically due to its remote location and served as a popular getaway for wealthy individuals.

The JRA members took the lodge’s owner, Kiyoshi Kojima, and his wife, Teruko, hostage. The assailants demanded the release of six JRA members who were in prison and a ransom of 300 million yen (approximately $2.5 million at that time). They threatened to kill the hostages if their demands were not met.

The Japanese government, led by Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka, faced a difficult decision. The situation was complicated by the fact that the JRA members were armed and had explosives. The government initially tried to negotiate with the terrorists to secure the release of the hostages.

During the negotiations, the JRA presented their demands, including the release of their imprisoned comrades and the payment of the ransom. The group also sought to draw attention to its revolutionary cause, using the hostage situation as a platform for their political message.

After several days of tense negotiations, the Japanese government decided to accede to the JRA’s demands. On March 1, 1972, the hostages were released unharmed, and the ransom was paid. The JRA members then fled the scene, escaping the authorities.

Following the incident, the Japanese government faced criticism for its handling of the crisis. The Asama-Sanso incident marked a turning point in Japan’s approach to terrorism, leading to increased security measures and a reassessment of counter-terrorism strategies.

Some of the JRA members involved in the incident were later captured, while others managed to evade authorities and escape abroad. The event also highlighted the global nature of terrorism and the challenges faced by governments in dealing with extremist groups.

The Asama-Sanso incident remains a significant chapter in Japan’s history, representing a moment when domestic terrorism captured the attention of the nation and prompted a reevaluation of security protocols.

Being a documentary-style film, Rain of Light is a fairly accurate recreation of the events of this act of terrorism. However, with any recreation, the exact events and how they are portrayed may differ slightly, undergoing slight variations or exacerbation to better fit the film’s appeal to audiences.

More Lists

16 Top Femme Fatales list – Sexy and Deadly in Equal Measure

The femme fatale is one of the most compelling and enduring archetypes in film history, captivating audiences with their blend of beauty, mystery, and danger. These enigmatic women are uniquely…

Dark Side of Pokémon – The Scariest and Creepiest Monsters

You’d be forgiven, dear reader, for being incredulous at something as childish as Pokémon appearing on our page. Yes, yes. Straight Outta Kanto can imagine what you’re thinking. Pokémon is…

Etheria Film Festival 2021 – Breaking Down and Rating The Shudder Short Film Fest

The Etheria Film Festival, or Etheria Film Night, is an annual film festival to showcase the latest short films by female directors. The first Festival was founded in 2014 by…

Love in the Time of Gore: 14 Horror Movies For Valentine’s Day Viewing

Throughout the history of horror cinema, love has found a way of permeating through even the most hardcore, violent, or gory flicks. Doomed lovers try in vein to save each…

Ranking Live-Action Performances of Junji Ito’s Tomie

Today, I will explore and rank an iconic character of the horror manga: Junji Ito’s Tomie. Tomie Kawakami is one of Junji Ito’s most popular characters and has become a…

Top 10 Deceitful Opening and Ending Songs for Unusually Dark and Disturbing Anime

Anime opening and ending songs are often the presentations for whatever show you want to watch for the first time. They try to convey the tone and themes that the…