Let’s jump straight to the point for once: Netflix has largely succeeded in adapting Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman, a popular and critically-acclaimed graphic novel which had been deemed “unfilmable”. With Gaiman onboard, a Doctor Who director (Jamie Childs) attached for most of the episodes and a cast comprised of veteran British actors, it’s ultimately the strong writing, as well as the grandiose cosmic imagery that end up elevating the show to must-see status – even though there are a few hurdles along the way.

Who is The Sandman?

Tom Sturridge plays the god of dreams, Morpheus – or, as he is known among his undying brethren, Dream of the Endless – responsible for overseeing the collective human (and non-human) unconscious, the act of dreaming and the oneiric geography: a world called the Dreaming where Morpheus reigns supreme, aided by librarian Lucienne and an assortment of quirky dream-denizens. While hunting for an escaped nightmare, the Corinthian (Boyd Holbrook), Dream is captured by the human mage Roderick Burgess (Charles Dance) and held in a prison-sphere for an entire century. Without Morpheus at his post, humanity starts suffering from a dream-sickness: some fall asleep and never wake up, while others are never able to sleep again.

The first episode deals with Dream’s imprisonment and Burgess’ bloodline, but like the first issue of the volume it is based on (Preludes and Nocturnes), it’s largely unremarkable – there are pros (getting the iconic Dream mask right, the skeletal appearance and some great SFX work – reminiscent of J.H. Williams III’s brilliant art from Sandman: Overture) and cons (an unconvincing Sturridge and plenty of cheap-looking shots) enough to generate buzz and keep viewers hooked. The biggest surprise might be the fact that The Sandman is not a Doctor Who clone. Episode two starts on the right foot, introducing Cain and Abel, the “original killer” and the “original murder victim” from the Bible, as dwellers of the Dreaming who have to make a sacrifice in order for Morpheus to regain some of his power, allowing Sturridge (who previously played Lord Byron in 2017’s Mary Shelley) to flex his acting muscles for the first time.

Sturridge’s Sandman is – initially – distant to a fault, lacking any human quirks. A pale vision who has to make up for his century-long absence, he plans and sacrifices pawns, always having an overview that only a truly timeless being can possess. Sturridge’s porcelain visage almost seems AI-generated at first, a brilliant reminder that Dream is supposed to be the prototype of a prototype of a prototype. This “uncanny valley” imagery, coupled with the fact that Morpheus is an embodiment of a (yet misunderstood) aspect of human life (the other Endless include Despair, Desire, Death, Delirium and Destruction), is what separates this show from the pack. Sandman‘s playground is wide and abstract, filled with cosmic corners, pocket-dimensions and dreamy detours, disallowing a wide emotional palette from Dream and making the viewer an active participant instead – with mind-blowing constructs and concepts, experiments with styles and forms and a god’s vision of humanity that often transcends good and evil.

How “Neil Gaiman” is it?

Ever since an early encounter with the Fates, it’s clear that the show will simply have too many “Gaiman-isms” in order for it to be a straightforward romp through different cities and eras. Episode three introduces Johanna Constantine (Jenna Coleman), the in-universe variation of Hellblazer‘s John Constantine (who was, nonetheless, also mentioned in the comics), and from there on, each entry is a pile-up of Gaiman tropes – a treat for fans, who have noted that the adaptation is one of the most faithful ones ever made.

Episode four features a match of ideas in Hell which pits Dream against Lucifer Morningstar (a spectacular Gwendoline Christie), doubling as the real turning point of the show. From there on, Sandman can simply be described as “near-perfect”, with the only issue being that some cheap-looking shots still make their way into every episode (more a Netflix problem than a Sandman problem). The show gradually expands its scope, each episode just getting better and better. As far as themes go, it’s dialectical to a fault, dealing with human achievements and failures, judgement and forgiveness, the small and the big picture, dreams and crushed hopes, selfishness and sacrifice. Humans having tea with gods, an obsession with eyes and surreal horror. Humanity’s best and worst, entire microcosms affected by Dream’s absence and return.

Gaiman, a master of the written word, able to come up with delightfully nostalgic avenues and find the most hidden of voices (as well as imitate the voice of his own favorite writers), dazzles with highly quotable lines of dialogue. Most often, however, delivered by Sturridge’s Dream, it comes across like streams of enveloping, poetic monologue. When Dream squares off against John Dee, it’s initially like seeing two giants from Gaiman’s Norse Mythology volume sharpening their axes, but the confrontation ends in a totally unexpected manner. When Death comforts the fallen, when Desire visualizes their domination over the other Endless, or when Lucifer contemplates the next move, you can feel the touch of a master storyteller at work. Nuance, feeling, decisiveness and wistful yearning – often with just a couple of words, making use of a rich vocabulary with a few “British-isms” here and there, Gaiman creates rounded characters and seems like he understands the human condition like only the best writers can. Each line of text is imbued with either the loneliness of an ancient god, or the impish attitude of a secondary, human character awakening and enjoying their fifteen minutes of fictional fame.

What are some standout episodes?

Episode five is going to make a lot of fans and critics happy, and will probably end up on a lot of end-of-year TV lists. Set in a diner and featuring a host of one-off characters, 24/7 reveals the importance of lies in human affairs and delivers a David Thewlis (playing a man who’s really tired of being lied to) performance for the ages. Double that bet for episode six, an adaptation of The Sound of Her Wings, one of the most representative issues of the original Sandman, introducing a major player in the ongoing story: an Endless who steps in to comfort Dream with some advice and a revelatory walk through town. There are enough praises to heap on Kirby Howell-Baptiste’s performance as Death to fill an entire book, and thankfully, Nerdist’s Michael Walsh wrote a downright beautiful analysis on the wide range of emotions conjured by the episode and its gut-wrenching impact, as it depicts the final moments of both ordinary and extraordinary people.

This episode is the first one in which we really see Dream changing, as he has to wrestle with the idea of having a true friend, a man who made a wager with Death herself, now an immortal with an inexhaustible supply of lust for life. Brilliantly depicting the passing of time and the cyclical nature of human existence, Sound of Her Wings is a somber meditation of loss, as well as an “advice from a friend” to appreciate life’s finer details: the highs as well as the lows, to take things one at a time with the vitality of a drunken-master.

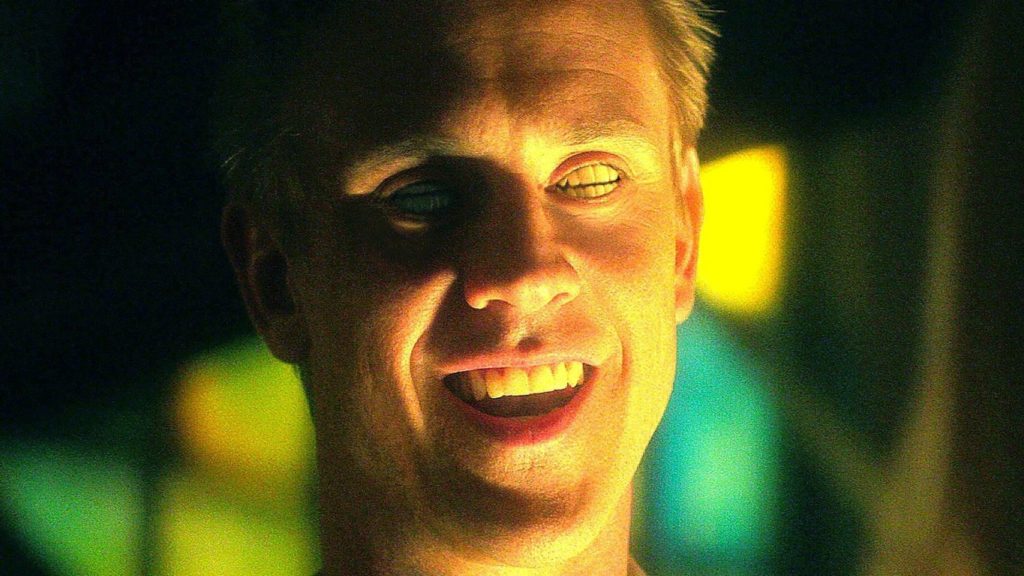

With episodes 7-10, Sandman breaks its own formula, turning to adapting the Rose Walker arc (a human dream-vortex, an “event” who is just as strong as Morpheus and can collapse the Dreaming entirely if left unchecked) and once again focusing on the Corinthian, who has amassed a legion of followers, a society of admiring trophy-killers who meet once per year at a “cereal convention” where their idol is set to perform as guest speaker. These episodes are the most similar to Gaiman’s American Gods, dealing with themes such as human desires, the refusal of self-sacrifice for the sake of abstract lines of thought, as well as different flavors of Americana. You can call Rose the one character who can stand toe to toe with the Dream Lord, the one human he is supposed to make a good impression upon, with the fate of the world hanging in the balance.

And of course, he doesn’t. As Dream seemingly endangers Rose’s entourage (which includes a man with a drag alter-ego, a woman called Barbie who dreams of travelling between dimensions, her Ken who is really fond of luxury cars, as well as Stephen Fry being Stephen Fry), Rose takes an increasingly reticent attitude towards Dream’s petulance. This marks the first time where Sturridge plays him as the villain he really can be (and is a lot more, in the original comics) for some people who dislike having their lives interrupted by otherworldly affairs.

What can genre fans look forward to the most?

Before talking about episode nine, Collectors, probably the major highlight for horror buffs, directed by none other than Revenge‘s Coralie Fargeat, we should mention one huge plus: that THE Dave McKean, the artist who worked on the covers of The Sandman volumes 1-75, came out of retirement in order to create the end credits for the Netflix show. If you’ve seen his work, read the mind-altering Cages, marveled at his illustrations in Gaiman’s Mr. Punch, or his art come alive in his own films, Mirrormask and Luna, you can only be thankful that McKean is involved with some capacity with The Sandman after all these years.

Containing visual motifs from each of Dream’s adventures, McKean’s purely functional end-credits double as eye-popping abstract visualizations. For the first episode, the sequence depicts a moth trapped in a bubble, tiredly flapping its wings. For Imperfect Hosts, the Cain and Abel episode, there’s a slow-moving snake circling its prey. A Hope In Hell’s end credits show Lucifer’s black wings and Dream’s mask on fire. Meanwhile, for Collectors, a pair of rhombuses grow ominously to resemble eyeballs, the favorite trophy of the infamous Corinthian.

As for Coralie Fargeat’s Collectors, it is – of course – a visual feast, a pun-filled “cereal”-killer convention story filled with hilarious (and frightening) innuendos: a benevolent-looking serial killer targeting children dubbing himself “Fun Land”, another calling himself “The Hammer of God”, a terrifying origin story involving pornography, surrounding chatter that feels ripped from the comicbook itself, and a convention panel called “Woman’s Work”. This standout episode, one which sees all of the remaining plotlines converging with the highest possible stakes, marks Fargeat’s first foray into directing English-language shows – it’s just a shame that we can’t credit her with being the one to introduce the Corinthian’s iconic set of eyes to the viewers, since that occurs in the final episode – and it shows that Gaiman is willing to put the most problematic stories from the comics into other people’s hands.

On the 19th of August, the streamer treated the fans to a bonus episode, The Dream of a Thousand Cats/Calliope, which adapts two issues from the third Sandman volume, Dream Country. Dream of a Thousand Cats is a short animated interlude, expertly timed by Netflix to coincide with the release of their own documentary about cats, and having a definite Graveyard Book/Cages vibe for Gaiman and McKean fans to enjoy. Its striking feline imagery definitely leaves an impression and will probably result in a flurry of screenshots and memes online. The rest, clocking at just about the standard 50 minutes, is an episode featuring an imprisoned muse, together with digs at pornography and fake male feminists. Calliope director Louise Hooper and writer Catherine Smyth-McMullen opt to hide some of the more unsavory and exploitative aspects of the original story from sight, leaving it to the viewer to infer them, in an attempt to give its title character more autonomy. It leaves the path open for future storylines (Orpheus!) and serves as another unexpected dip into the horror genre, after 24/7 and Collectors.

In the end…

Dream of the Endless proves to be a god who’s prone to the occasional bout of anger as well as unnatural levels of enduring pain and feeling empathy for those in need. Netflix’s adaptation is a work that provokes the reader’s imagination more and more as it progresses, providing “comic-accuracy” in the least expected of places. Whether you’re a seasoned reader or a new fan, if you can get past some inconsistencies and go with the occasional tonal imbalance, this portrayal of the Dream Lord’s exploits gets a lot right and, as the readers already know, it’s only showing an ounce of its true potential. The real highlights of Gaiman’s massive creation are yet to follow, but in getting the first two volumes right, he proves that his Netflix gamble has staying power and that his writing can make it the number one Netflix series in just about every country on Earth. The Sandman deserves its popularity as well as the critical acclaim, and Netflix is onto a winning combination, especially if they can hire more seasoned directors while keeping the high budget. If you’re hoping for the series to get renewed, make sure to stream all the episodes on Netflix and tell your friends – as series creator Neil Gaiman has recently weighed in that all the acclaim and the number one status could still prove insufficient in the face of a possible cancellation. (However, the fact that we were spared a network TV version of Sandman is all the confirmation we need that we’re not yet living in the darkest possible universe.)

More Film Reviews

Monster Brawl (2011) Film Review – It Was a Graveyard Smash

I’ve always enjoyed debating an entertaining hypothetical scenario, and the crazier the better; from insane vs. match-ups of different competing franchises, to the animal kingdom, or even warring countries from…

The Lair (2022) Film Review | Toronto After Dark Film Festival

In 2017, the United States Air Force carried out an airstrike in the Nangarhar Province, Afghanistan. Deploying the largest non-nuclear bomb in their arsenal (the MOAB), they aimed to destroy…

The Exorcist: Believer (2023) Film Review – The Devil Never Gives Up But Neither Does Hollywood

Widely accepted as “the scariest film of all time”, William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973) has stood the test of time and will probably be talked about until the very end…

August Underground (2001) Film Review – Found Footage Filth

August Underground is a 2001 extreme found footage film, written and directed by Fred Vogel with additional writing from Allen Peters. The film was produced by TOETAG Pictures with effects…

Secrets of a Woman’s Prison 2 (1968) Film Review – Brutality Behind Bars

Despite being one of Japan’s biggest film studios throughout the late 40s and 50s during the golden age of Japanese cinema, Daiei was struggling by the mid-60s and had to…

Black Friday (2021) Film Review – Capitalism is Hell

In the anti-consumerist horror comedy Black Friday, a ragtag group of toy store employees try to fight off an infectious horde of customers during the worst day of the year…