“I came out early, I couldn’t take it”

“I hated it”

“I loved it and won’t have a word said against it!”

– Quotes overheard in the foyer, after having seen Skinamarink.

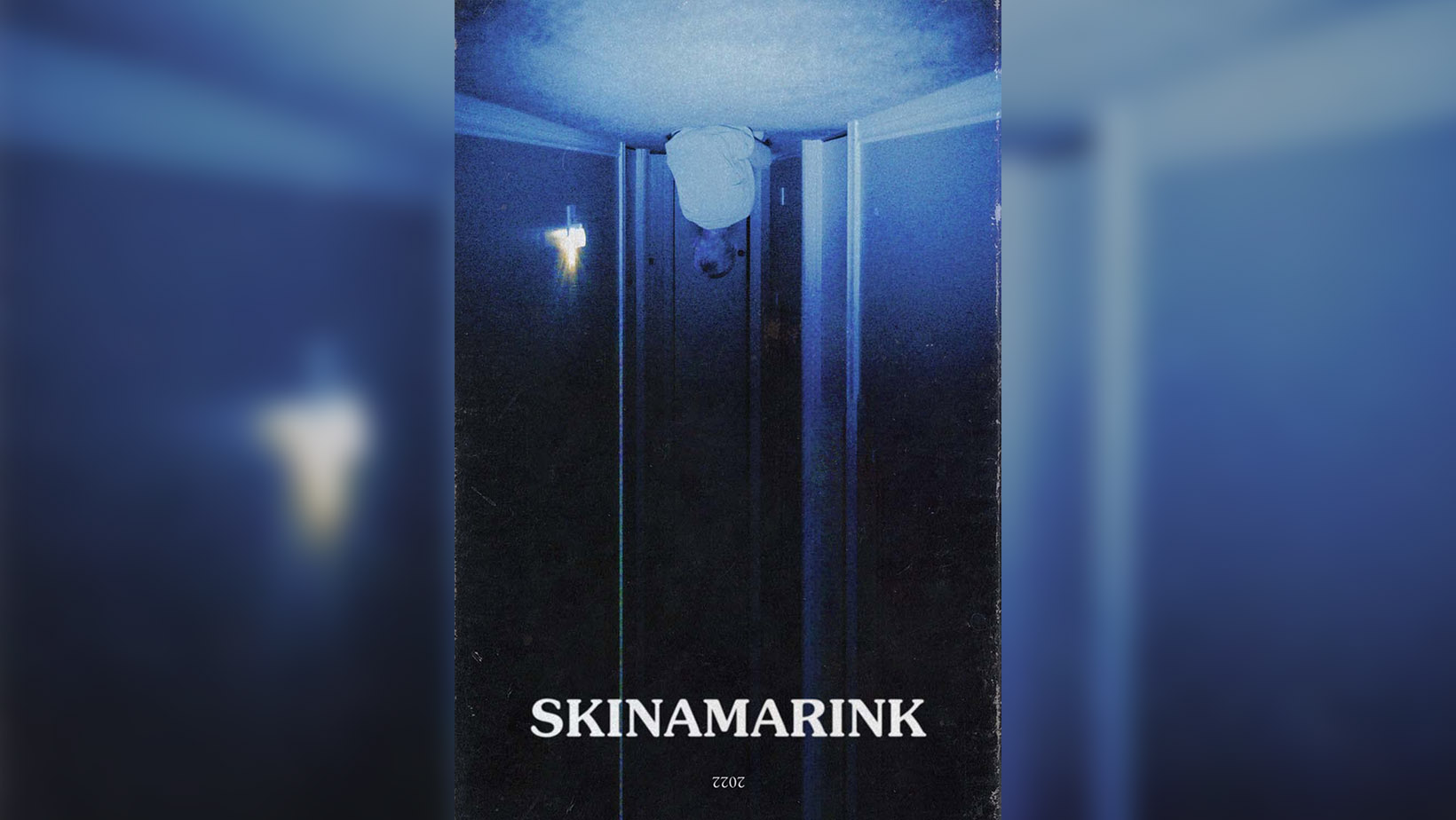

Written and directed by Kyle Edward Ball and shot on a micro-budget at his childhood Canadian home, Skinamarink (2022) is inspired by a childhood nightmare. Pirated, and leaked online, the film comes with an illicit sense of seeing something you shouldn’t, a cursed film that had audience members talking of how the cinema had to seek local council permission to show the film at all.

Dated in 1995 and suggested at covering over 500 days, the vague outline of a story involves two infant children, a haunted family home, and a demonic presence, but Skinamarink is not overly concerned with coherent plots or understandable narrative structure.

The film is comprised of blurred, rather abstract, images of the domestic space. Nothing is clearly shown, the camera views everything from a child’s perspective, gazing up at the corner of rooms, at doorways from carpet level, or concerned with close-ups of floors strewn with toys.

Set entirely in the early hours there is no sunlight and illumination only ever comes from the absent parent’s childminder; the television, weak lamps and room lights, or shaking torches, which all fail to fully penetrate the ever-present darkness. The degraded film stock overlays the blackness with writhing static that seems to undulate as you strain and peer into unilluminated spaces.

The addition of foley effects adds to the sense of the uncanny as children’s feet pad tentatively over the worn carpet, or the sound of heavy, sleep-filled, breathing fills the speakers. This sound design is unsettling, leaping from unintelligible whispers, or hushed subtitled dialogue, to jarring clangs, distorted beyond understanding, and back again to barely audible hums and short-lived vibrations. Old-fashioned animation plays on the television, along with its quirky orchestral accompaniment, reverberating through adjoining rooms.

The jump scares, of which there are few, rely on loud noises and jarring image shifts, but Skinamarink is far more concerned with creating a pervasive atmosphere of anxiety and dread. Like a Lynchian dreamscape, the film looks to tap into the viewer’s repressed childhood psychology. The infants, Keeley and Kevin, are effectively abandoned, with their innocence and naivety exacerbating the fear that comes from the unknown, which they are forced to face. The unknown adult world, their parents’ eerie behaviour, the nighttime, and the entity whose influence grows more malevolent throughout the film, all lurk in the shadows. At one point we’re asked to “Look under the bed” which conjured, for me, a childlike reimagining of David Lynch’s journey behind the dinner in Mulholland Drive (2001).

The domestic space, usually so safe and reassuring, is contorted by the darkness. Doorways disappear and objects move, defying gravity, all at the whim of an unknown hand. Faces are only seen twice, are horribly distorted, and at no time is dialogue ever seen being uttered. Questions are asked, but to whom is often unclear, and childish imploring contrasts with deep, demonic suggestions to self-harm, reminiscent of Black Peter in The Vvitch (2015).

Skinamarink is, simply put, extremely divisive and will make audiences question what they want, or expect, from a film. I personally feel that it is more an experiment, a piece of visual art, rather than a movie, and as such will cause many cinema-goers a great deal of frustration, anger, and disappointment as it will not offer what many feel is expected from a film-watching experience. Skinamarink would feel more at home projected onto the whitewashed walls of an art gallery and, at 100 minutes long. Undoubtedly overstaying its welcome, trying the viewer’s patience as it takes a lot of effort to watch the grainy images and distorted sounds. It does, however, succeed in producing a disorientating, dread-filled, nightmare that will deeply affect those open to its unclear, narrative-averse charms. Its lack of clear story, obtuse, prolonged, art house wall-gazing, and blurry figures will, however, conversely send many to their keyboards to loudly berate its “stupidity”, declaring how “nothing happens” in BLOCK CAPITALS, desperate to prove how they have not been duped by the Emperor’s new clothes.

There are a number of original, unsettling experiences to be found within Skinamrink’s walls but, for me, although I’m very pleased such experimental art exists and enjoyed the experience, it is an interesting idea far too overstretched that will upset countless hundreds who want their cinema to be less obtuse, challenging and clearcut.

Skinamarink (2022) will be arriving on Blu-ray, DVD, and digital on July 3rd from Acorn Media International

More Film Reviews

The Degenerates is a 2021 extreme found footage horror film, written and directed by Jonathan Doe and produced under Vile Video Productions. The film is the second entry to Jonathan’s… Witness protection isn’t enough to keep a mother and her young daughter safe, as the vigilantes hunting them down catch up to the pair. They want a confession the mother… Evoking youth in serious horror narratives will always touch a soft spot for many; however, The Innocents not only brings a frightening scenario upon a small group of children, it… Until c.1080 CE, the Temple of Uppsala stood tall and proud outside Gamla Uppsala, Sweden. The temple served as a place of worship and community dedicated to pagan deities such… “The reunion of two sisters after one of them has just been released from a mental institution is marred when a stay at their abandoned childhood home threatens to reveal… As a newcomer to the Halloween franchise, I am less experienced with the later sequels to have any attachment to the worldbuilding, and I controversially thought Rob Zombie’s film was…The Degenerates (2021) Film Review – An Astounding, Unforgettable Experience

Motherly (2021) Film Review – Don’t underestimate a mother’s love

The Innocents (2021) Film Review – A Difficult Journey Into Childhood Violence

The Ritual (2017) Film Analysis – The Demonization of Paganism

Two Sisters Film Review – Psychological Horror Among Siblings

Halloween Kills Film Review (2021) – Michael Walks Home