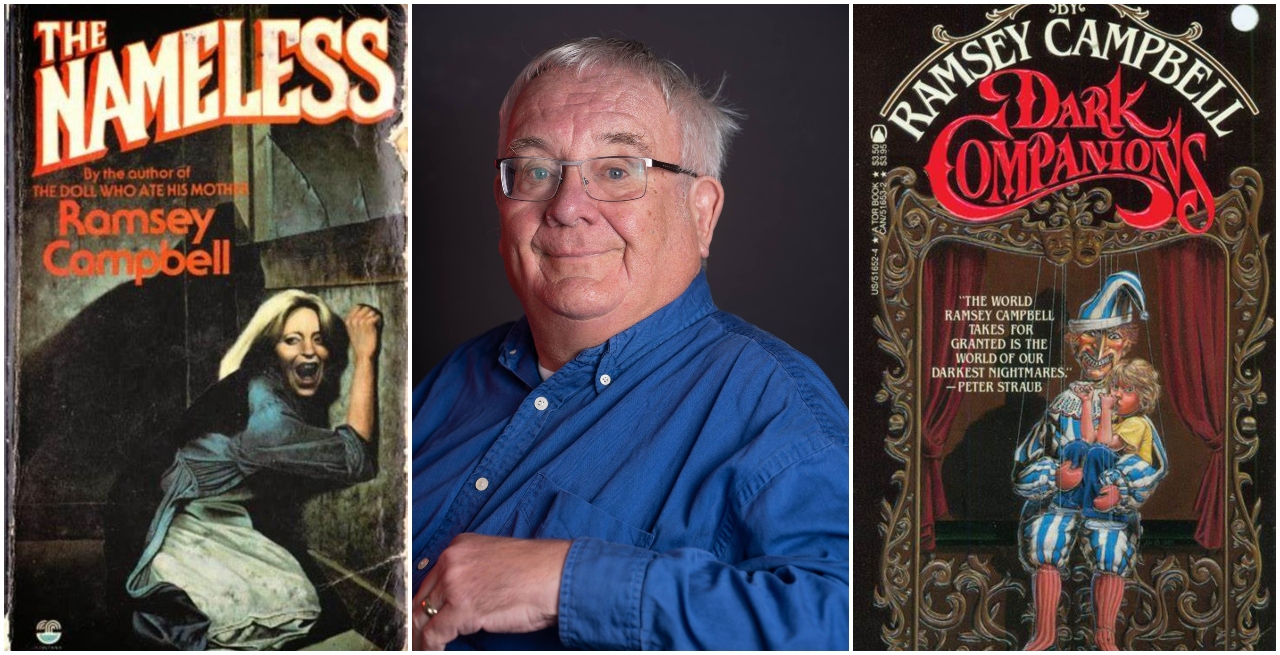

A distinguished British horror author, who’s been the recipient of various awards in fiction and considered amongst the most revered veterans of the industry, Ramsey Campbell has established a strong legacy already to be regarded on level with many of the most esteemed writers of today. Prolific is an understatement, he’s served as both editor and critic of horror in addition to his main pursuits; Ramsey is also heavily involved with the horror community at large, receptive as he is amiable.

Ramsey Campbell’s extensive experience in horror serves as an invaluable resource for insights into the nature of the field itself, whether vocationally or more abstractly, and it’s a delight we have the opportunity to interview such a heavyweight of horror fiction.

Who was the most influential horror figure in your formative years? Furthermore, which is your favourite horror author to read casually now as you’ve matured?

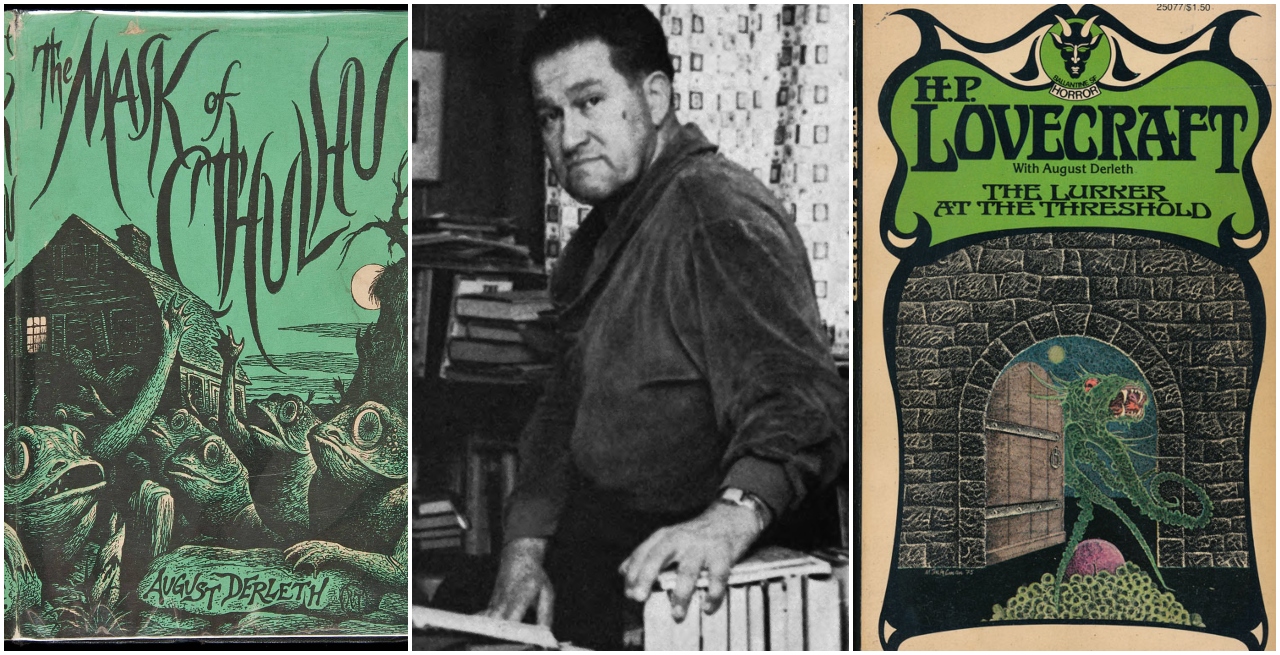

RC: Influential on my early stuff once I focused on what I valued most in the field – Lovecraft, without question, and specifically the collection Cry Horror, his first ever to be published in British paperback (in 1960). Though this wasn’t a conscious plan, the early stories in my first Arkham House book work through several of his modes – the florid and Poesque, the documentary style, the cosmic saga… As the book progresses it grows more like me, though not particularly fruitfully. August Derleth’s advice helped in that regard. Throughout the book I was trying to capture a sense of the cosmic, however feebly.

I don’t think one can read Robert Aickman casually, but he certainly repays rereading, and nobody’s work in the field gives me more pleasure on so many levels – elegance of prose, evocative allusiveness and elusiveness, the delights of the enigma, the joys of dark humour. I’ll always return to him.

Which tale of Lovecraft do you consider his most powerful and why does it resonate with you?

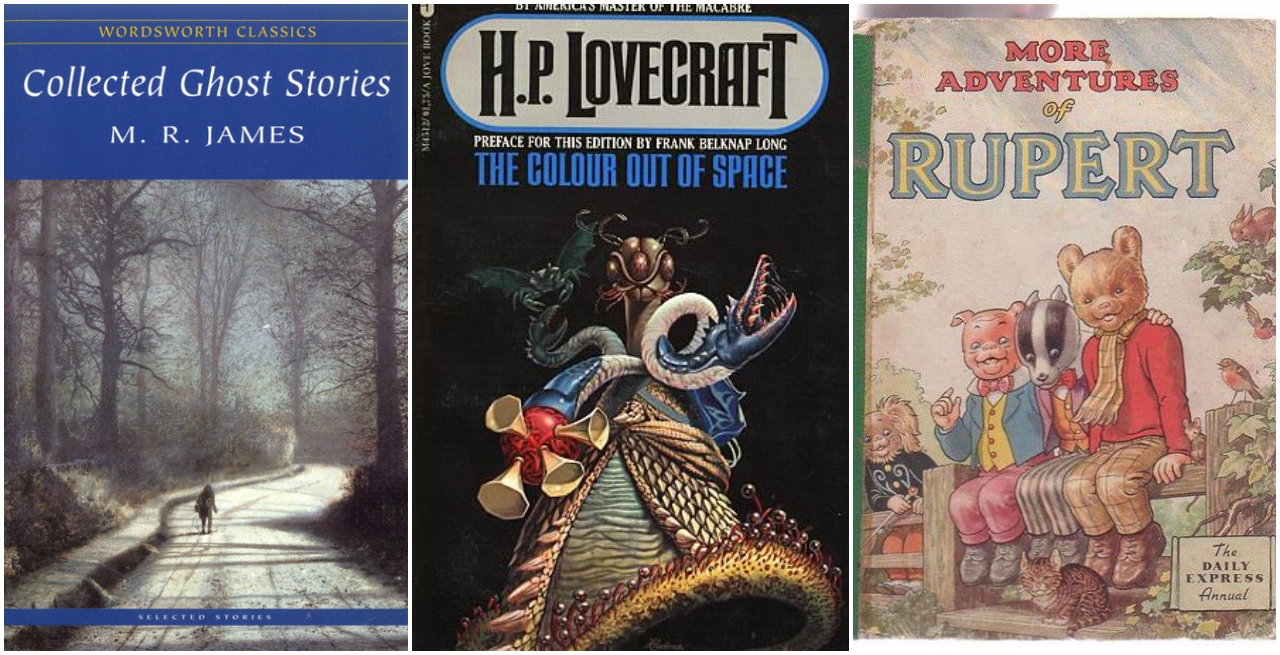

RC: I think “The Colour out of Space”. It distils his sense of cosmic terror into the purest symbol or evocation he ever created. As in all his best work, the modulation of prose and the care for structure are exemplary, and crucial to the effect of the tale. For me it ranks with “The White People” and “The Willows” at the highest level.

Which of yours works do you consider the epitome of your style? Additionally, which one would you proudly recommend for a first-time reader of your bibliography?

RC: Lord! It depends which style. It has altered so much over the decades that even though I tend to feel locked into my present approach to prose, there’s no predicting what that may be in a few years. I’ve tried to strip it down, which is a function of how severely I rewrite – once upon a time I would salvage as much of the first draft as I thought I could justify, whereas of late every aspect of the first draft has to justify itself to me, otherwise it’s excised or reworked. So I can only make a few selections: Midnight Sun for uncanny lyricism, The Grin of the Dark for comedy of paranoia, the trilogy as a bid for cosmic terror, most of my recent novels for lightness of touch (I hope). Those would be recommendations, and as an overview of my shorter tales, the two volumes of Phantasmagorical Stories from PS Publishing.

What’s the importance of a prose to you? Poetry? Coherence?

Both of those, and the pleasure of phrasing and imagery I haven’t encountered before – the ability to make us (reader and writer alike) look afresh at what we’ve taken for granted.

You’ve been writing since 11 and so the craft has been a journey for you. Are there any lessons along the way that you would like to share?

RC: Don’t despair, even when your work is rejected. Keep writing, and don’t leave work unfinished.

Learn to enjoy rewriting as soon as you can – every piece of work needs it, believe me. Tell as much of the truth as you can. Always compose at least the first sentence before you sit down to write. Identify your most creative time to write and, if you can, work then – if not, try at least to write some of your new piece every day until it’s finished. Just to be clear, I’m only suggesting that people see if these approaches work for them, not insisting that they should.

Do you think horror has legitimacy as high art and not pulp, genre work?

RC: At its best, most certainly. Horror fiction started as a branch of literature, and it still has roots there. Look how many mainstream writers, especially of short stories, have contributed to the field. In quite a few instances those tales are the ones they’re best or even only remembered for. Let’s also remember that many specialists in horror have produced work at least as fine. We don’t need outsiders to raise the standard, but equally those who add good work shouldn’t be dismissed as outsiders.

More academically, S. T. Joshi has done amazing for scholarship in weird fiction, highlighting many otherwise obscure authors. Is there any author you feel has been overlooked?

RC: Perhaps Adrian Ross? The Hole of the Pit is quite something (as Bob Hadji pointed out decades ago). For other undeservedly neglected writers in our field, look to the anthologies of Hugh Lamb and Richard Dalby – more recently, Johnny Mains.

Most writers have close contemporaries who were an influence as much as support – is there anybody who’s noteworthy for how supportive they’ve been along your career?

August Derleth at the outset – my first editor and publisher, and then pretty well my surrogate father by correspondence for a decade. When he died I missed him more than my real (very largely unseen though not absent) father.

You’ve been an editor and even an essayist – how did you fancy those roles versus more purely creative endeavours?

RC: They’re all rewarding. Particular pleasures of editing include making tales available I think many readers won’t know – Villy Sørensen’s “Child’s Play”, for instance – and discovering and promoting new writers. I’m proud to have helped launch quite a few of those – Steve Rasnic Tem, Marianne Leconte, Marc Laidlaw, Adam Nevill and others. As for non-fiction, I’d say that can be creative too.

You worked at the Arkham House and it’s sure prestigious to the minds of any weird fiction fan – what’s your strongest memory of there?

RC: I’d say my first professional publication back in 1962, in the Derleth anthology Dark Mind, Dark Heart. The tale (“The Church in High Street”) was to some extent rewritten and condensed by him, but all the same, sharing a contents page with the likes of Bob Bloch, whose stories had haunted my earlier years, was quite an experience for a sixteen-year-old. Years later Bob and I would meet and become friends.

Of all the eras to horror across time, which one was your most favourite and why?

RC: There’s a great deal of competition—our own day is certainly a candidate, given the amount of talent and imagination on display—but if it’s to be the era productive of the greatest number of the greatest works, I’d say the Edwardian. “The Willows”, “The White People”, “The Monkey’s Paw”, “The Voice in the Night”, several of M. R. James’s finest tales—that was quite a decade, and hugely influential.

You see many rising talents, they’re the next generation – has anybody stood out for you?

RC: There are so many considerable writers at work just now that I believe we’re enjoying one of the golden ages of the field, but I’m wary of listing them for fear of (pretty inevitably, the way my old brain acts) omitting some who should be celebrated. I’d direct everyone to Steve Jones’ annual anthology of best new horror, and Ellen Datlow’s equivalent series. I doubt you’ll find anyone I wouldn’t endorse.

If you are to be a critic for horror, where do you seek the most value in the merit as

constituting that?

RC: The selection and modulation of the most appropriate prose to convey the kind of horror the tale involves—the uncanny, the psychological, the cosmic, the insidiously disquieting, quite possibly a combination—and an attention to whatever structure is best suited to the particular material. Engagement of imagination, the writer’s and hence the reader’s. Those are the ideals, at any rate.

What is your earliest memory of fear, and did this have any impact on your writing?

RC: Reading Rupert Bear gave me my first taste of terror in fiction. One of the many presents I found in a bulging pillowcase at the end of my bed at Christmas 1947 was a copy of More Adventures of Rupert. The tale that haunted my nights was “Rupert’s Christmas Tree”, in which Rupert acquires a magical tree that decamps after the festivities and returns to its home in the woods. Perhaps this is meant as a charming fantasy for children, but the details—the small high voice from the tree, the creaking that Rupert hears in the night, the trail of earth he follows from the tub in his house, above all the prancing silhouette that inclines towards him the star it has in place of a head—are surely the stuff of adult supernatural fiction. I think I got my start in the field right there, and many of my preoccupations must derive from my early childhood.

For years I believed that my first memory dated from when I was three years old. I suspect that’s because of its understandable vividness. I recall little about my father up to this point, although I have a random memory of his telling me that early in the morning you could see ladies’ fingers in the sky—I imagine he meant clouds turned pink by the dawn. He used to take me out on Sundays, and on the only occasion that has stayed in my mind we walked across the line at the end of a platform at Broadgreen Station instead of using the pedestrian bridge. When we came home he told my mother, to her horror. They had a hearty argument above my head that ended with her ordering him out of the house.

The front door contained nine small panes of glass, reaching from chest level to the top of the door. My father blocked the door from outside as my mother tried to close it; presumably they were struggling for the last word in the argument. My mother’s hand went through one of the panes. I remember her dripping bright red blood and crying out that he had deliberately closed the door on her hand. The sight of blood except for my own has distressed me ever since. A neighbour—Gladys Trenery from next door—looked after me while her husband took my mother to hospital. I suppose they humoured her to calm her down, but at the time I thought they were accepting her version of the incident. Since my father had fled, I tried to set the record straight. What did I know about it? I was only three years old. I don’t think it’s fanciful to relate one of my recurring themes—the difference between perception and reality—to this.

I forget the aftermath, but years later my mother said that she had subsequently asked me in front of my father if I wanted to go out with him again. How could I have said yes when it might have led to another such scene? It feels as if that was the last I saw of my father, though it may not have been. Certainly relations between my parents grew steadily worse, until soon they met hardly at all. One reason must have been that my father (who was in his late forties, my mother having been thirty-six when I was born) felt robbed of his only son. For the rest of the childhood he was mostly unseen—the footsteps beyond the door, the turning doorknob—and my mother’s accounts of him only turned him more monstrous. She was an undiagnosed paranoid schizophrenic.

What are your favourite horror movies?

RC: Nosferatu. King Kong. I Walked with a Zombie (if it isn’t too delicate to be called one). Night of the Demon (my absolute favourite). Psycho. Peeping Tom. Taxi Driver. Lost Highway, though I’m tempted to list half a dozen Lynch titles.

What’s your favourite colour as something simple?

RC: Green, the colour of the uncanny and of renewal. May those two be related?

Which horror icon is your favourite amongst all the traditional kinds (e.g. vampires, ghosts, mummies)?

RC: I avoid them when possible, except for the ghost, which is hospitable to any number of developments – so that’s mine.

What do you think about the modern horror industry in writing?

RC: Publishing, do you mean? I’m delighted to see mainstream publishers supporting our field again, none more so than all my friends at the splendid Flame Tree Press. The independents are vital in all senses too, and I wouldn’t be without the essential PS Publishing, where Pete and Nicky Crowther and their team have supported my tales since the turn of the century.

What are your latest projects – would you like to speak about those?

RC: My most recently completed novel is Fellstones, named for the mysterious seven stones that give a village near the Lakes its name. Our protagonist has been called back there by his adoptive family, only to remember why he left, while the cosmic secret underlying the local folklore begins to grow clear and active. Soon I hope to start writing The Lonely Lands, the supernatural novel after that. Alongside these I’ve been working on Six Stooges and Counting, a study of the Three Stooges in all their incarnations.

We would like to thank Ramsey Campbell for his time, knowledge and fantastic attitude. You can follow Ramsey Campbell on Twitter or visit his site! Ramsey Campbell’s latest project is the ‘Three Births of Daoloth’ trilogy and the first two volumes, The Searching Dead and Born to the Dark‘, are available from Flame Tree Publishing. The third book in this trilogy, The Way of The Worm, is also planned for release on the 22nd of March, 2022.

More Interviews:

Celebrating Women in Horror Month: The Author Series (Part 1)

Conversations With Three Influential Women in Horror While many in the horror community celebrate Women in Horror Month in February, the Grimoire of Horror is choosing to observe the celebration…

Interview with Alex DiVincenzo and James Cilano of Witter Entertainment [Video Content]

Check out our newest interview with James Cilano and Alex DiVincenzo, the masterminds behind Witter Entertainment and Broke Horror Fan. They have been hard at work releasing beloved classics as…

Daemon Manx’s New Series Is Destined For the Big Screen! The Ojanox – Spoiler Free Book Review and Author Interview

Hey Mike Flanagan, we’ve found your next big project! New indie horror authors are crawling out of the woodwork every week, and just like indie films, their products are hit…

Interview with Director/Editor Thomas Burke – Found Footage Aficionado

Thomas Burke is an award-winning filmmaker and editor based out of Austin, Texas. He has spent over the last decade freelancing in various production roles including film directing, acting, producing…

Some say the countdown begun when the first man spoke, others say it started at the Atomic Age. It’s the Doomsday Clock and we are each a variable to it.

Welcome to Carcosa where Godot lies! Surreality and satire are I.

I put the a(tom)ic into the major bomb. Tom’s the name!

![Interview with Alex DiVincenzo and James Cilano of Witter Entertainment [Video Content]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Interview-Witter-Entertainment-365x180.jpg)