When looking at the origins of sukeban media, the first representation of the genre came in 1967 with Taro Bonten’s Modern Delinquent Girl Stories manga; with the first proper sukeban film, Girl Boss: Broken Justice, not coming later until 1969. That isn’t to say, however, that vestiges of these themes weren’t explored prior to this. An example of this prototypical sukeban film can be seen in Daiei’s Kanto Woman Yakuza from 1968. Though there is one film released in 1966 that predates both this and the Taro Bonten manga: Three She-Cats.

Three She-Cats was based on the story Seduction Plan by Shinji Fujiwara, best known for his hard-boiled neo-noir stories which had already received numerous film adaptations (most notably A Colt is My Passport). What is particularly notable with Three She-Cats isn’t so much its source material but the person who adapted it. The screenplay was written by Iwao Yamazaki, none other than the same writer of Girl Boss; Broken Justice as well as Nikkatsu’s other early forays into the sukeban genre. With this knowledge, Three She-Cats becomes a very interesting look into the ideas which would later form the foundations of sukeban cinema. In the family tree of pinky violence, Three She-Cats arguably sits at the top, especially with its seemingly very direct influence on Toei’s Three Pretty Devils.

The film opens with a young woman, Yoko (Machiko Yashiro) who is being abducted by a gangster; she is so desperate to escape that she jumps from his moving car. However, her efforts are to no avail and he drags her to a hotel room after beating her into submission. There he r*pes her before tying her up and forcibly tattooing her, no doubt with the intention of pimping her out later on. When he lets his guard down after the tattooing, Yoko quickly grabs a knife off the table and stabs him through the stomach before making her escape. Unfortunately, her problems have only just begun and it turns out that her rapist belonged to the yakuza who are quick to retaliate in their revenge, kicking down the door of her mother’s bar. Yoko and her family decide that her only option is to flee town and hope that the yakuza don’t track her down.

On the train to the city of Atami where she will seek refuge with her mother’s friend, Yoko encounters a woman, Midori (Ryuko Mizukami), who is being harassed by an older man. Yoko is quick to step in to fend off the potential threat and the two women quickly become friends with Midori offering her a job in her nightclub. At the station, they walk past Mari (Yumiko Nogawa) who will later become the third she-cat. At first, seeming to be a naïve tourist, Mari takes the perhaps unwise decision to accept a lift from a total stranger. Yoko and Midori encounter Mari once more when they enter an inn and hear screaming upstairs. On their way to investigate the commotion, they find Mari isn’t as innocent as she first seemed and is blackmailing the man, holding a pistol in one hand. After getting the full story, the three women decide to team up and rob every sleaze ball that they can get their hands on.

In the meantime, Yoko isn’t quite as safe as she thinks as it turns out the man she stabbed survived his wounds and is keener than ever to get his revenge. With a couple of successful schemes under their belt and their purses bursting with cash, the three she-cats are able to move onto Yokohama when Atami becomes too hot, but the yakuza are only ever a few steps behind. However, the women are as much a threat to themselves as the yakuza; eager to replicate their early success, the girls become ever more reckless in their plans. Their reliance on seduction means they have to constantly put their own bodies on the line which continually risks their safety at the hands of the men they plan to rob, extort and blackmail. Before long they find themselves in the deep end with little to no means of escape as they discover that the life of a thief is wrought with danger.

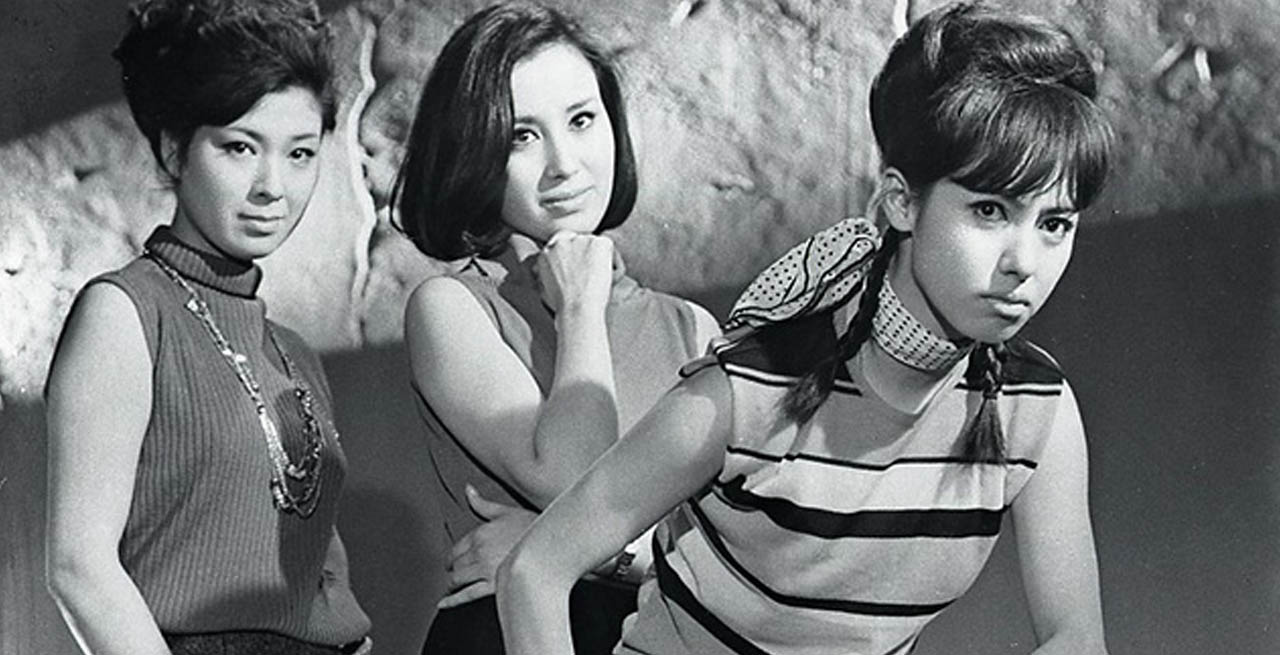

The film’s greatest strength is also the greatest strength of the she-cats themselves: the differences between its protagonists. Yoko is the demure classical Japanese beauty, almost always wearing a kimono; Midori is the straight-talking independent modern woman, and Mari is the precocious and feisty young punk – very much the definition of a she-cat. The women’s opposing personalities are the key to their success as it guarantees that, between the three of them, at least one of them will meet the taste of almost any man they set their eyes on. For the viewer, it is a pleasure to see how each woman approaches and reacts to every situation differently and how their character types both complement and, at times, work against each other.

It is easy to say that Yumiko Nogawa steals the show, though that was always going to be the way with her character who is by far the loudest and brash of the three. However, looking past Nogawa’s initial dominance, Machiko Yashiro arguably gives the best performance as she subtly portrays Yoko’s development from a naturally shy and subdued woman to a devious seductress like her two partners. It is clear that she feels deeply uncomfortable in her new surroundings but perseveres in order to survive; she might have chosen at first to run from the yakuza, but she is far from cowardly and seizes her new life by the horns.

Overall the film is very well balanced with the threat of the chasing yakuza keeping a constant level of background tension to drive the film forward. Many later sukeban films fell foul of spending too much time treading water as they showed their protagonists stealing and plotting, though Three She-Cats ensures that its characters remain the main focus of the film and not their actions. Director Motomu Ida’s prior career consisted primarily of yakuza films and from that experience he clearly has an eye for action. When the handful of fight scenes do ignite, they are supremely tense and exciting – a highlight is definitely the sequence where Mari has to fend off a club filled with gangsters, firing her pistol off in all directions as she desperately fights to keep the upper hand.

Nevertheless, Ida resists focusing too much on the action and lets the film run at its own pace, favouring slower moments with the characters to let the drama naturally unfold rather than constantly shifting them from one peril to the next. He makes it clear that this is a character-driven film and allows the audience ample time with each of our three protagonists, paying careful attention to all of them equally. A lesser director or writer might have made this Yumiko Nogawa’s film (the posters certainly want to push this narrative) but both he and Iwao Yamazaki clearly recognise the strength that the characters of both Yoko and Midori offer and build the film around the whole team.

If there is one main criticism of the film it’s that the final act feels extremely rushed. Whilst the ending itself is quite fitting and suitably nihilistic, it is very much at odds with the pacing of everything that came before it. The film, despite its tension, is far from being fast-paced and the sudden commitment to tie everything up in the last 10 minutes spoils the care taken up to that point. However, it is clear that this is all quite intentional rather than through a lack of finesse. The sudden change certainly reflects how the women have found themselves quickly sinking as their situations all get the better of them, though the way they are almost tossed aside feels quite jarring, especially for the amount of time spent developing their characters so well.

Whilst it is far from a typical sukeban film, it is clear to see how Three She-Cats paved the way. Its focus on independent women from different walks of life bucking the trend of what society, and men, deemed appropriate of them is the key driving factor of all sukeban cinema. The film flips the patriarchy on its head by having the she-cats use men for their advantage, though it is wise not to go as far as portraying them as infallible. The characters’ naivety and vulnerability are plain for everyone to see and are part of what makes the film so charming. Despite what they may project externally, each of these women is very human and has their own justifications for who they have become. They are not morally bankrupt, nor even particularly nasty, and this is how the audience is truly made to identify with them: just three regular women who have had to adapt to deal with their travails doing whatever it takes to survive, even if that means risking everything.

More Film Reviews

Pinku softcore porn films were big business for Japanese studios throughout the 1970s; so lucrative were these films, that when Nikkatsu was on the verge of bankruptcy in 1971, they… Welcome to Raccoon City is very different in style from the Resident Evil movies featuring Milla Jovovich. While also live-action, it embraces a very different feel and quality, though is… Stanleyville (2021) has a simple premise: five contestants compete in a contest to win a brand-new habanero-orange compact SUV. Maria joins hoping for a chance at transcendence, but the other… Lady Snowblood is Toshiya Fujita’s 1973 Japanese exploitation flick that inspired the likes of Tarantino’s Kill Bill and countless other directors, featuring the beautiful Meiko Kaji, also famous as Lady… Tod Browning is best known for directing creepy, silent films such as Freaks and Dracula, but before he made movies, he was a circus performer and carnival sideshow host. Perhaps… Finding a sense of belonging is built into the core of human existence. In Poser 2021, the debut feature from filmmakers Noah Dixon and Ori Segev, we delve deep into…Semi-Document: Occult Sex (1974) Film Review – Exploring the Powers of ESP (Extrasensory Perversion)

Resident Evil: Welcome to Raccoon City (2021) Review – Itchy, Tasty!

Stanleyville (2021) Film Review: Is the Car Really Worth It?

Lady Snowblood Review (1973) – The Finest Japanese Exploitation

The Show (1927) Film Review- A Fun Silent Carnival Ride

Poser (2021) Film Review – The Art of Fitting In

Hi, I have a borderline obsession with Japanese showa-era culture with much of my free time spent either consuming or researching said culture. Apparently I’m now writing about it as well to share all the useless knowledge I have acquired after countless hours surfing the web and peeling through books and magazines.