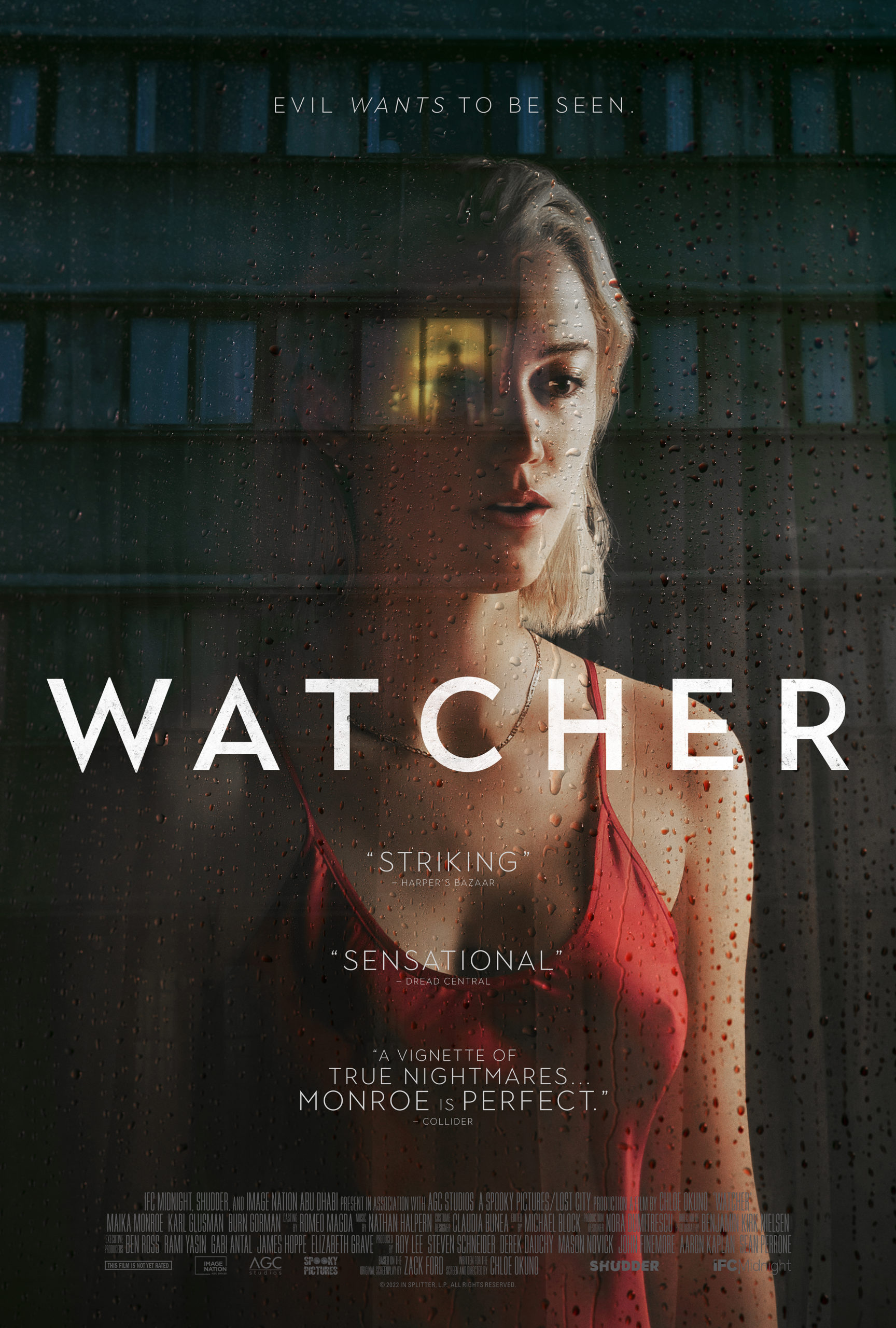

Chloe Okuno’s Watcher, which delighted lucky Sundance Festival-goers earlier this year, is a step forward for the horror genre and doubles as a neat entry point (for those curious) into the landscape of contemporary Romanian cinema and culture. Shot in Bucharest and featuring the amazing Maika Monroe alongside some of the most recognizable Romanian actors working today, Watcher is a smart fish-out-of-water paranoid thriller that takes the “double culture shock” concept and gives it a neat Hitchcockian twist, managing to be the most delightful look at urban anxiety since The Scary of Sixty-First, albeit for entirely different reasons.

The mostly agreed-upon definition of double culture shock is “moving abroad to be able to live with a husband from a different culture“. In Watcher, Monroe plays Julia, a woman who relocates with her husband to a flat in Bucharest, Romania, and immediately begins to feel uncomfortable, both because of the expected cultural differences and the unexpected nosy stranger from across the street who keeps peering into her life (not to mention the Rimaru-like serial killer dubbed “the Spider” who leaves a trail of decapitated victims in their wake). Because the husband is mostly busy with work and the locals can’t be bothered to believe her complaints, Julia is left to investigate the stranger on her own, and she meets an array of colorful characters on the way, such as: a partially-deaf old lady in search of her missing cat, a sex worker with a heart of gold, the “boyfriend with a mean temper” played by Daniel Nuta (High Strung Free Dance, Adela), and a German expat played by Burn Gorman (Torchwood) looking after his ailing father. All the while Julia’s struggling to pick up a bit of Romanian and often has to rely on the kindness of strangers when finding herself in eerie situations.

Romanians are known to be one of the most hospitable people in the world, a fact only confirmed by the thoughtful collective response to the Ukraine refugee situation. However, the Romanian post-communist “transition society” cannot agree on a variety of topics, from vaccines to the so-called “great global reset”. Watcher illustrates a lot of problems inherent in Romanian society through the eyes of a sensible outsider, problems which will be instantly recognizable to Romanian viewers and which constantly build upon the feeling of dread that the movie expertly contours around its main character.

Watcher‘s beauty lies in the details, some of it being “flavor” Romanian dialogue, with the movie achieving an alienating effect akin to what Julia is experiencing during her stay in Bucharest. It remains to be seen whether the DVD and VOD release will have subtitles for the Romanian parts, which do occur pretty frequently around the English-speaking protagonist. The film focuses on domestic violence, paper-thin walls in Bucharest apartment buildings leading to the lack of any notion of privacy, violent outbursts often accompanied by violent language, an indifferent and incompetent police force, an exploitative and bragging-oriented culture, and the Romanian “neaoș” sense of humor (an essentially untranslatable word which combines a careless attitude with political incorrectness, vulgarity and linguistic quirks).

Some examples of what Julia has to deal with are a grisly description of the serial killer’s MO being laughed away and followed by “hey, have I told you that one about the hunter?“, or the opening cab scene in which the driver immediately lobs the “frumoasa” (beautiful) word at her in front of her husband and then does it again and again. Julia is met with doubt and sexism at almost every turn: from employees, strangers, and friends alike, and while initially she is frozen in place, terrified by the difficulty of blending in and trying to stay sane, she eventually takes a more active stance towards resolving the main issue – that of the stalker, whether he is “the Spider” or not and whether she can do anything about it in a country where most don’t seem to believe that “bothering”, coupled with “looking in” and repeatedly “following” someone even constitutes stalking.

It shows that Okuno (a filmmaker who, if we’re going by her short film Slut, opts to go for the jugular) worked closely with her Romanian counterparts but ultimately had the final say, and the movie shies away from really painting Bucharest in a bad light; in the sense that the city – “a clash of the Belle Époque and Communism” famed for its gray apartment buildings, its recent state of decay, its food and the loud nightlife – could have come off a lot worse. Watcher aims at being thrilling and rewarding more than trying to point fingers at a specific someone or something, and Okuno makes it clear that it’s Julia’s inquisitive personality that puts her in danger most of all, coupled with the lack of a support system.

Only if one looks closely can they notice just about everyone in the movie being unfriendly or just unhelpful to Julia, yelling at her, speaking very loudly in Romanian when she barely has any clue about what they’re saying, banging on doors and never bothering to ask about her feelings, always caring about their petty worries. There are characters who function as temporary helpers only to end up as bitter disappointments, but there are, more often that not, encounters which chip away at Julia’s sense of well-being: the “meltean” (a word which defines a coarse, rough man) eating “seminte” (sunflower seeds) at the movies, the “homeless subway guy” talking to himself, or even the “Steaua Bucuresti 1947” graffiti on the buildings hinting at the average Romanian male’s obsession with soccer.

However, there are some bits which don’t work as well as they could, such as the scenes which feature the aforementioned sex worker named Irina; a character who is a good idea on paper and Julia’s only friend in Bucharest (bonding over her actually believing Julia – or being too busy to deny her claims – and her knowledge of the English language), Irina serves as a liaison between the movie’s protagonist and the “Bucharest wall of indifference”, but ultimately just provides viewers with mounting unease on whether her allegiances will eventually shift (it doesn’t help that when Julia visits the club where Irina works, she is saluted by a vampire-like doorman inviting her to “come in, come in”). Non-Romanians will probably take delight in seeing “the dark underbelly” of Bucharest and will most likely not notice that the Irina character is a well-worn staple in Romanian cinema, always destined for a grisly fate. Thankfully, Watcher isn’t Hostel, and it isn’t Berlin Syndrome either – it doesn’t wallow in despair and doesn’t want to (just) shock. It wants to add to the “woman in the window” genre that Netflix parodied last year, and could, by itself, kick-start a new wave within said genre. And, speaking of Netflix, it’s not The Weekend Away either – the portrayal of East-European society is a lot more convincing and not at all exploitative.

By now, being a Maika Monroe-led horror film should come with certain audience expectations from diehard fans of the actor; some will likely expect for any character she plays to overcome all obstacles, because they’ve seen a lot of films in which that happens and only one or two in which it doesn’t. Watcher provides a great opportunity for Monroe fans to test that theory, and if Julia isn’t as assertive as other protagonists played by the iconic actor, she is at least as tough as the “other” Julia, the protagonist of Netflix’s much-maligned Tau. Statistically, you still can’t bet against a protagonist played by Monroe, but do expect for Watcher to toy with your expectations (and Julia’s chances of survival) in the most thrilling ways possible as she gets closer and closer to the heart of the mystery.

There are a few things to consider from the Romanian cinema landscape, too: Romanian film-making has, in the past few years, entered a new phase in which everyone seems much more open to approaching genre territory. Bogdan George Apetri’s Unidentified is probably our best modern revenge-thriller, tackling the themes of systemic racism and police brutality. When Silver Berlin Bear winner Florin Șerban released his unorthodox take on Hamlet this year, it doubled as one of the “purest” slasher films ever in modern Romanian cinema, and last year’s Întregalde had the premise and the first act of a backwoods-horror movie, only for it to opt for a more humanizing direction. Then there’s Adrian Țofei’s Be My Cat: A Film For Anne, which we’ve covered here at Grimoire. If the non-mainstream side of Romanian cinema basically excels at characters studies (Mia Misses Her Revenge, Otto The Barbarian, The Father Who Moves Mountains) and ripped-from-the-headlines stories, it can safely be said that local filmmakers have begun and will continue siphoning the power of genre. Still, there’s nothing that Romanian cinema can offer that’s quite like hearing Maika Monroe learn to swear in Romanian (her “du-te-n p***a m*-*ii” is one of the most satisfying cursing and the smartest bit of meta-fanservice since Kaho casually spoke some pretty good Romanian in Sion Sono’s Tokyo Vampire Hotel).

Overall, Watcher is one of the best films of 2022, a near-masterpiece that manages to be both respectful and decisive, containing a lot of homages but also a novel approach towards building dread and instilling a sense of unease in viewers. That it could kick-start a post-“woman in the window” sub-genre and perfectly illustrates the double culture-shock concept are its best achievements, but it also offers a superb Maika Monroe performance, together with one of the best ending shots in recent memory. Constantly toying with audience expectations and featuring a woman who sees a world in which she appears distorted, a world which gazes back at her with a tired eye but doesn’t ever believe her, the movie is also one of the best conversation openers of the first half of 2022. After enjoying its theatrical run, Watcher was released on VOD on June 21st.

More Film Reviews

Established in 2009, the American Genre Film Archive is a non-profit which seeks to collect, conserve and distribute genre films in order to preserve their legacy. From shot-on-video slashers and… After the tragic loss of his mother, Oliver is threatened with state custody unless he can find a new family. And so Oliver does just that… by digging one up… She Kills is a 2016 American action horror film, written and directed by Ron Bonk. Boasting a huge filmography as an executive producer, Ron is known as the proprietor of… When a colleague forwarded me the trailer for Night’s End with the note “I think this is up your alley,” he couldn’t have been more right…. by the trailer at least…. Almost entirely free of dialogue, Looky-loo (2024) gives viewers the view from a killer’s own eyes as he stalks and plans multiple murders. The nameless killer, gains confidence with each… “People don’t really connect, you know.” A sentiment that is often shared among film fans about some of the most eminent artists in the industry is that they were and/or…Sometimes Aunt Martha Does Dreadful Things (1971) Film Review | There’s something about Martha…

The Loneliest Boy in the World (2022) – Just Dig Up A Best Friend If You Need One

She Kills (2016) Film Review – Right in the Dick

Night’s End (2020) Film Review: The Ghosts of Insomnia

Looky-loo (2024) Film Review – Through the Eyes of A Killer [Unnamed Footage Festival 7]

Revisiting ‘Kairo’ During a Global Pandemic in the Age of Social Media

![Looky-loo (2024) Film Review – Through the Eyes of A Killer [Unnamed Footage Festival 7]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Look-Loo-2023-review-365x180.jpg)