Published while he was still in college, Bret Easton Ellis’ debut novel Less Than Zero (1985) established themes of isolation and excess still present in his work today. The narrator, a disaffected young adult named Clay, sets himself apart from his friends and longs to leave Los Angeles. He appears again in Ellis’ second book, Rules of Attraction (1987), now longing to return. Ellis’ sophomore novel also introduces Sean Bateman, whose brother Patrick makes a brief appearance, before cementing himself in pop culture history as the narrator of the follow-up, American Psycho (1991). Ellis’ third book remains his most popular and controversial, but he has been steadily writing and infrequently publishing novels since.

It is his fifth novel, Lunar Park (2005), that has the most in common with his latest. An homage to Stephen King, it is arguably Ellis’ first true horror novel. Writing for the first time in past tense, Ellis casts a version of himself as the narrator with a fictional wife and children. When a guest attends a Halloween party dressed as Patrick Bateman, Ellis realises how much his own creation haunts him, and he endeavours to destroy it. Lunar Park is a criminally underrated book and an ultimately successful experiment. Ellis returns to King territory now with his latest workThe Shards, a book about memory and loss of innocence.

17-year-old Bret Ellis lives in a privileged Los Angeles bubble he calls ‘empire’. Filling his days with sex and drugs and fast cars, Bret finds himself detached from his friends’ lives, playing a role he increasingly despises. Further upsetting his existence is the arrival of Robert Mallory, a new boy in the senior class. Enigmatic and devastatingly handsome, for Bret, Mallory is an object of equal suspicion, disgust, and desire. This burgeoning obsession collides with Bret’s interest in a new serial killer (dubbed the Trawler) and a cult whose influence is being felt across the city.

The Shards is a slow, dense book, whose true nature is deliberately obfuscated by our unreliable narrator. Whereas Bret the 17-year-old is naïve and curious, often to his detriment, Bret the writer is omniscient, revealing horrors his young self cannot hope to understand. In this way, the novel thrives on a form of dramatic irony; the narrator knows and does not know the truth, simultaneously. Whatever horrors await Bret and his friends in the fall of 1981 are survived by him at least, but the impact of these horrors is not lessened. In fact, the book argues that it is the loss of innocence itself, rather than the inevitable loss of life, that is the true tragedy.

However, Bret the writer recounts events with a certain numbness, and from the very beginning establishes their value as a kind of fiction. 17-year-old Bret wants to be a writer, and he is already tinkering with a draft of Less Than Zero. 58-year-old Bret has already sent that novel (and five others, not including The Shards) out into the world. It is Bret’s friendship with a girl called Susan Reynolds that inspires the detachment ubiquitous in his work. Susan is beautiful and numb. Recurrent is Ultravox’s ‘Vienna’ – This means nothing to me… – which underscores everything, and indeed recalls Patrick Bateman’s pronouncement that his “confession has meant nothing…” Bret and his friend Thom playfight on the floor of a trendy new space in LA, pausing only to stare up at the haunting music video.

Music of the period defines Bret’s life. He barrels down the highway in his Mercedes, Blondie’s ‘Call Me’ blaring from a mixtape, in what he calls his “American Gigolo moment.” A visit to a friend is haunted by The Specials’ ‘Ghost Town’. These songs and many others form the soundtrack to Bret’s life; he interprets and reinterprets their lyrics as he sees fit and, for the reader, evokes a vibrant, immediately recognisable world. Bret also loves film. When a producer invites him for drinks to discuss a project, we (and Bret) know what this man really wants, but Bret plays along, wanting to see what happens. This numb acceptance (“Welcome to LA,” he tells a boy who has just been groped) extends to the prose itself when Ellis moves the ‘camera’ around and has young Bret see himself from far away, a sudden, voyeuristic touch.

If Bret is being watched, he is also very much a watcher. He notes Susan’s hesitation to hold hands with her boyfriend, and the intimate body language between Robert and other boys. Bret’s observations are a kind of research; he studies and, sometimes, copies. When his friends deride his ‘zombie’ attitude, he endeavours to perform as “the tangible participant”. Others perform out of necessity. Ryan Vaughn, a football player, confides in Bret his disdain for the other students: their privileged lives, their fake problems. Ryan is closeted, playing the macho jock role for survival. Meanwhile, Matt Kellner, a perpetually stoned loner, seems totally unaware of roles and performances. Bret embarks on sexual and emotional relationships with both.

Those familiar with Ellis’ work will already be prepared for graphic sex and violence. It is established early on that, before disappearing and killing his selected victims, the Trawler begins with home invasions, psychological warfare, and pet abductions. 58-year-old Bret reveals to us details of these horrific crimes before 17-year-old Bret discovers them. The timeline is deliberately confused – Bret tells us something, and then he tells us that he didn’t know it yet – and breadcrumbs are dropped sporadically throughout the book. Cold callers, horoscopes, and animal sacrifices appear less frequently than Bret’s musings about half-naked boys in locker rooms, and his carefully planned drug-taking regimen. This is a slow yet ultimately rewarding experience, and Ellis works hard to land the horrific dénouement.

The Shards captures a numb, hazy Los Angeles in sharp counterpoint to Bret’s exacting commentary and detail-heavy prose. Ellis the writer claims not to care about politics, which is of course a position only a privileged person can take. His work has always been politically charged, whether or not he admits it. If we believe the murders in American Psycho are real, not hallucinated, then Trump-loving Patrick Bateman predicted Trump’s braggadocio by shooting people in the street and getting away with it because of who he is by some accident of birth. The privileged teens of The Shards can be excused their ignorance by virtue of their youth, but there is a reason only Bret seems to care that a serial killer’s pattern aligns with the new boy’s visits to LA and that an animal-sacrificing cult is closing in.

The Shards is available to purchase now. It was published by Knopf in the US, and by Swift Press in the UK.

More Book Reviews

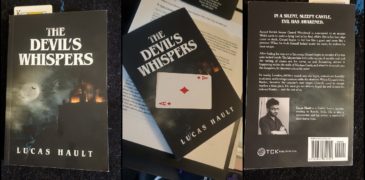

Eric Schaller’s latest anthology, Voice of the Stranger, starts with a foreword exploring the birth of its title. Deftly put Schaller explains, “The title for my collection is taken from… Preston Allen’s 2024 novel, I Disappeared Them is a riveting exploration of human complexity, blending elements of mystery, psychological depth, and societal commentary into a compelling narrative. It evokes disgust… Hello, GoH friends! Dustin here with another round of Recent Reads. For this one, we have three reads with long titles, and I swear that wasn’t intentional. There’s Eric David… Hollywood horrors, entities from beyond the grave, and body horror mutations: these can be found within my recent reads which I’ll be sharing with you, dear reader. For this edition… When I first held the novel The Devil’s Whispers in my hands, I was immediately thrilled to see the influence of classic horror. Lucas Hault not only promises to entertain… Created as a response to criticism levied at queer writers – often by queer readers – The Book of Queer Saints comprises 13 gorgeous, gruesome tales of queer victims and…Voice of the Stranger (2023) Book Review: An Unsettling, Intoxicating Voice in Horror Literature

I Disappeared Them: A Novel (2024) Book Review – The Inner Workings of the Mind of a Serial Killer

Recent Reads: Long Night at Lake Never and Other Reads

Recent Reads: Coldheart Canyon, Scry for Help, Wilder Girls

The Devil’s Whispers by Lucas Hault – Book Review

The Book of Queer Saints (2022) Book Review – 13 Tales of Vengeance, Villainy and Victims

Isabelle is a writer from the UK who enjoys alternative manga and horror films. When not writing, you can probably find Isabelle buying books or obsessing over Martin and Lewis.