The early 90s saw the horror genre in more box office peril than it had seen in a while. The hits of the 80s, such as Jason Vorhees and Freddy Krueger, had been sent to hell and reported dead, respectively. And audiences that had shown up for previous return installments were diminishing. What love is found for Jason Goes To Hell is entirely out of a retrospective critique; it had landed with a thud as hard as Jason’s corpse hitting the depths of Crystal Lake.

Freddy fared worse. Rachel Talalay’s turn at the director’s chair after a long history with New Line was reviled, often appearing on worst of the year lists. It didn’t help that it was nearly three times more expensive than Jason to make. Clearly, some new life needed to be injected into the genre, but nothing had been successful. Despite attempts at new killers meeting with moderate early success like Bernard Rose’s Candyman, there wasn’t the same drive to push potential icons much further. Rose had no interest, pitching an adaptation of Clive Barker’s “The Midnight Meat Train” instead.

The sequels inevitably wound up as direct to video releases, right along the latest Tremors film.

The solution turned out to be a young screenwriter named Kevin Williamson with an idea for a film called “Scary Movie.” When he did finally sit down to write it, he claims it took a matter of days. He even had an idea for a director – friend Tom McLoughlin.

McLoughlin had met with success in the 80s revitalizing the Friday the 13th series with part six, which recognized the series’ age and knew the only way forward was to inject a little humour. One wonders just how much would have been different without the involvement of Harvey Weinstein and eventually Wes Craven; were it McLoughlin, would it have been Sean Cunningham producing? Weinstein’s role is the most unfortunate aspect of Scream‘s legacy. There’s no reason not to believe the accusations of Rose McGowan and others, and Weinstein is rightfully rotting in prison with a punishment that doesn’t seem nearly enough.

Is there guilt attached to enjoying Scream today? Yes, and we’ll address it in due time. But given the current reclamation of Buffy The Vampire Slayer by fans outraged by its creator’s abusive behavior, it’s not unreasonable to look at Scream mostly independent of Weinstein…until the third.

Scream opens with what you can imagine the elevator pitch would have been. (Scream, for all its PR, was not written on spec, and Williamson sent out pitches long before writing it). Drew Barrymore answers a phone in an isolated farmhouse. It’s meant to be familiar, nostalgic even. For horror fans, the phone killer had been en vogue since the earliest days of the slasher, with Black Christmas introducing the menacing caller.

Williamson’s script is the kind that teachers base lectures around, starting with a killer opener. The cold open is roughly 15 minutes, a short film in itself like When A Stranger Calls, and it lets you know precisely what kind of movie it is. Within two minutes of conversation, Barrymore’s teen turns the conversation to horror movies, and the age of the post-modern slasher began in earnest.

Screenwriters easily throw accusations around scripts like this being too clinical; pointing out examples that seem pulled from lectures they sat through in University. Outside of some residual bitterness at Scream‘s success that writers likely harbour, these criticisms aren’t without merit. But there is still something immensely satisfying about seeing screenwriting 101 paying off – even more when you’re a layman.

It’s devotion to efficiency is part of what makes Scream such a joy.

It’s also worth noting that at no point in Scream are we subjected to the line, “As you know…”

After a few cute film references (including a tacit acknowledgment that sequels to Craven’s own Elm Street “sucked”…perhaps even the one he had a hand in scripting), Barrymore’s stunt casting is revealed and she’s hung on a tree not unlike the first ballet dancer in Suspiria. Then we’re introduced to our leads. Sydney (Neve Campbell), the daughter of a murdered local whose death reporter Gail Weathers (Courteney Cox) made her name off. Her boyfriend Billy (Skeet Ulrich), who may intentionally have been cast to resemble Johnny Depp. He certainly crawls up to her window much as Depp did in Elm Street. Stu (Matthew Lillard), who has very little character outside of being a little offbeat.

And finally Randy (Jamie Kennedy), the horror film buff who realizes the kind of situation they’re in right away.

Williamson ensures at least some of the references Randy makes play, even if he throws in some more obscure for the already initiated.

For the most part, they work, even when they approach groan-worthy. At one point, Rose McGowan’s Tatum tells Sydney her life is starting to look like a “Wes Carpenter” movie. It’s a joke I imagine began life when the writer had McLoughlin in mind, but it doesn’t inspire more than an eyeroll when you think about Craven including it himself.

Still, it was a bit of a gamble to include even slightly obscure film in-jokes, callbacks and references and expect mainstream audiences to get them in 1996. And it should be mentioned that, as central as Williamson was to every aspect of the Scream franchise, these are Wes Craven films from start to finish. Craven had dipped his toe in meta territory before, with the noncanon (and best) sequel to A Nightmare on Elm Street, New Nightmare. That film wasn’t nearly as accessible and suffered both critically and commercially for it. While it’s not a bad freshman effort, especially in light of what followed, there’s the inescapable feeling that Craven is slipping back into his Professor days, before he turned to low-rent porn. With Williamson, Craven found a voice that felt fresh, not stuffy or lecturing.

By the 90s, pop culture had just become accessible enough for these references to work. VHS had beaten Beta 15 years earlier, with most major horror releases and even poular cult works availible at your local video stores. The rise of HBO and Showtime also gave viewers the chance to catch late night screenings of direct to video releases and pure schlock. Imagine trying to make a Howling reference without the public consciousness necessary for viewers to understand. When Williamson does it, he makes sure to include the fact it has “E.T.’s mom in it.”

And the references play a more important role than just name-checking. Scream‘s self-awareness is smart enough not to stop at just mimicking previous horror efforts, it uses them to further its satirical points. Early on, Randy makes the claim that their situation could be easily navigated if they just followed the rules of horror logic. But the film is already setting up its own horror logic, and Randy becomes hilariously useless in the film’s final act, spending most of it drunk on a couch, even warning a character on the television while the actual danger is right behind him.

Late in the film, the teens become something of unreliable narrators when talking film, mistaking commonly held beliefs as fact even when the evidence is in front of them. People often talk about remembering more than you actually see in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, with your imagination making Tobe Hooper’s suggestive camerawork worse than anything onscreen. This appears to be the case with the teenagers watching Halloween here, who immediately claim they see blood that’s too red after a teenager is stabbed. Halloween famously used less than a bucket of fake blood, and that scene actually features none. For mistakes such as this, IMDB has a whole section entitled “Incorrectly regarded as goofs”.

And that’s part of Scream‘s charm. Again, well-drawn characters work in the film’s favour. It’s not that they’re more informed than most victims, in fact, that occasionally hampers them in later films.

Sadly, it’s that same care and attention to character that seemed to stop Williamson from being able to kill anyone significant off. When Harvey Weinstein said the script had dead air in act two, a long chunk without any death, Williamson added in the death of Principal Himbry (Henry Winkler, probably the first time anyone realized his older potential). To his credit, he makes the death central to the story – it’s the appearance of Himbry’s corpse that empties out the farmhouse of most guests for the third act. But it doesn’t fit the killers’ M.O.

It helps that the killers have an M.O., despite them claiming otherwise. Scream came under fire, like many of its kind, for inspiring real-life copycats. But the murderers having motives unrelated to cinema gives Williamson and Craven a pre-emptive defense. In the end, it was Billy and Stu, the former having killed Sydney’s mother after learning of her affair with his father. Stu is just psychotic. Their reveal, that it was two and not just one, wasn’t necessarily difficult to figure out, but we’re easily distracted by compelling, likable characters – a rarity in slashers. By the third act, the film sets up some kills that a detective would stumble over. It owes just as much to Agatha Christie as it does John Carpenter, if not more. Carpenter objected to the idea that his job was to preserve virginity, but no one had issues with Williamson taking a whodunnit approach to the slasher genre. Slashers have always borrowed from this kind of fiction, though it had fallen out of favor by the 90s. Serial killers were the stuff of airport novels, not masked maniacs. In 1996, the other major psycho films were Primal Fear, Fear, The Fan and The Glimmer Man.

But the callback to older drawing-room mysteries is part of the reason Scream saw success outside of the horror community. I know, as I’m sure you do, many people who enjoy it just for the mystery. In their own way, slashers were always extremely gory detective stories, and Scream capitalised on it to satisfying results.

Despite breakthroughs just years away, Scream never gets too hung up on technology. This is a happy accident, as cell phones were not universal; still the realm of hack stand-up comedians who picked up stools and dictionaries to mock the experience. The phones were smaller, the jokes were still selling. Scream was probably the last film of its kind as much as it was a new one, where plot holes concerning cell service and caller I.D. weren’t an issue and When A Stranger Calls‘ sequel was only a few years old.

This was immediately addressed after Scream 2‘s cold open, which features yet another star (Jada Pinkett – not yet Smith) brutally slain – at a screening of the film based on the events of the first. Sydney is now in college, waking in her dorm to a ringing phone. Alas, a prank caller is quickly found out by caller I.D.

Things are going well until the murders begin again. Sydney is a drama major with a frat boy boyfriend (Jerry O’Connell), Randy is naturally in an unspecified film class. Timothy Olyphant is….present. And Gail Weathers returns to cover the opening kill, along with the recently freed Cotton Weary (Liev Schreiber, reprising a walk-on role from the first film) who was just cleared of murdering Sydney’s mother.

There’s a lot to like in Scream 2. Craven is still adept at building an atmosphere, a slew of in-jokes and much more creative kills. There’s a lot of focus in the conversations about Scream revolving around Williamson, but these films are very much Wes Craven films – some of his best. He rarely stepped out of horror, but you could see his abilities at work in the more mystery and drama-driven scenes here. But he’s still a great horror filmmaker, generating some truly suspenseful moments. And with the added gore, Scream 2 fully embraces its slasher roots.

Of course, more gore is what we were promised in the trailer. Early in the film, Randy and Dewey (David Arquette) discuss the nature of sequels, which include more blood and a larger body count. As expected, much of Randy’s dialogue is insider knowledge of slasher sequels, as meta as possible.

All of the standard criticisms of sequels by nature being inferior films is on full display for Randy to pick apart. It’s not always a bad thing, it can occasionally even be funny. Particularly well-handled are the near shot-for-shot recreations with much worse dialogue in Stab, the in-movie Scream. A scene from the first film between Skeet Ulrich and Campbell is rewritten to sound like an episode of Degrassi, with Luke Wilson and Tori Spelling replacing the actors.

But Randy, by the second film, is not Randy, he’s entirely taken over by the actor. Jamie Kennedy’s offscreen persona was only just beginning, but you could tell he was trying to perfect it here. And it’s a little more than grating.

Worse still, Randy’s criticisms feature one major oversight: At no point does he talk about their proclivity for redundancy. It’d be especially astute of Randy, considering the film repeats a lot of the same beats as the first.

A lot of the problems with Scream 2 stem from the internet. It was in it’s earliest home incarnation, and the fear of spoilers suddenly became real. Today audiences live in fear of being told what happens before they have a chance to see it themselves, but there was a time it was less of a concern. The fact that it is suggests more about audiences than the quality of the film.

The original ending featured two very different killers – Sydney’s African American female roommate, breaking the traditional white male stereotype, and her boyfriend once again. Ulrich’s reveal in the first was likely the larger surprise for audiences, and doing it again would have been the perfect middle finger for audiences who would just naturally assume they wouldn’t repeat events that much.

Alas, it was leaked, forcing Williamson to think of a quick replacement. Ultimately, he went with Billy’s mother (Laurie Metcalfe) and the always present Timothy Olyphant.

The ending doesn’t fit, it’s true, but Williamson keeps it exciting enough to play ignore the worst aspects of it. And he did have the courage to do something he never dared try again – he kills off a major character.

It’s just as well that Randy dies, and he has one of the best deaths in the movie, with a clever cat-and-mouse phone call lead-up before being yanked into a van. His death is the ultimate irony, too. Throughout the film, he speaks about sequels raising the stakes. He just wasn’t aware he was talking about himself.

Williamson is not bad with little ironies like that, but his stretch for dramatic irony is a little too heavy-handed. Sydney is framed as a modern-day Cassandra, which only somewhat fits the finished film, but certainly lines up with the rest of the franchise.

The other aspect that really saves the second from its script problems are the performances. Two films in, and Campbell, Arquette and Cox had settled well into their roles, adding layers of maturity when appropriate, resorting to childish trantrums when not. It helps to have veterans like Metcalfe and David Warner around, and newcomers like Schreiber in a very early role proves himself an excellent unbalanced red herring.

Scream 2 fared almost equally well at the box office, and audiences and critics were surprisingly kind to it’s flaws. Williamson had created a rare creature, a slasher film in which the characters were worth caring about beyond one film. And he was signed on for at least three.

There was always talk both in Scream and on the conservative airwaves about onscreen violence inspiring real life violence. Scream even fell under fire after its release for several stabbings across the United States. And it only got worse after April, 20, 1999. Hitler’s birthday. International Pot Smoking Day. And the day Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold walked into Columbine High, killing 12 classmates and one teacher before taking the coward’s way out.

If conversations about the media and violence were heated then, they exploded onto the floors of Congress after, with a special focus on horror films specifically. Barrymore’s opening scene was played for the committee as a prime example.

Williamson left Scream 3, but he did leave a five-page treatment for newcomer Ehren Kruger to work with. Kruger won the Nicholl Fellowship for his script for Arlington Road, but since Scream 3 he’s found a home working on the Transformers sequels.

Scream 3 fits more in line with them. Louder, brassier, more obnoxious. The film references this time around are all painfully obvious, and the “star” deaths are far less glamorous despite it being nearly 75 percent more costly. Somehow, Drew Barrymore to Sarah Michelle Gellar to…I suppose Scream 3’s equivalent would be Jenny McCarthy?

McCarthy’s not the opening kill, Kruger changes that up by making it much more significant. This time around, Schrieber is offed after hosting his all-too preciously named TV show 100% Cotton. It’s a perfectly acceptable end for the character, but given Schrieber’s unhinged work in the previous film, it robs you of a lot of potential fun.

Sydney is in seclusion, taking calls for a battered women’s hotline, when she and the gang are suddenly thrust into hollywood on the set of Stab 3 (we never even got a glimpse of the second film). The third in-movie movie is produced by a Roger Corman-type (Lance Henriksen) who knew Sydney’s mother during her brief attempt at a Hollywood career. It later comes out that he hosted a party where she was gang r*ped.

I recall hating Scream 3 when I saw it, but watching it now presents a fresh horror that almost made it difficult to finish.

Lance Henriksen is not Roger Corman. Lance Henriksen is Harvey Weinstein.

Weinstein’s sexual deviancy was the kind of open secret Hollywood should have never allowed. So it’s especially uncomfortable watching a character who was probably modeled in part on Weinstein (not so he’d notice) without actually trying to do anything about it. It’s the kind of in-joke the audience doesn’t want to be in on, whether it was intentional or not.

Scream 3 is a mess. If Scream was a smart satire, funny because the characters were just naturally amusing, then the third entry is bad comedy. The jokes don’t land, the characters are thinly drawn or annoying. If Jay and Silent Bob showing up as themselves isn’t jumping the shark, then we need a new definition. And the killer – singular for once – is the weakest by far. During the gang r*pe, Sydney’s mother had a son who she abandoned. Now he’s directing Stab 3 and offing cast members. The first film was incredibly smart at how it meted out exposition. This is a dump right at what should be the most exciting climax of a trilogy.

Again, this wasn’t entirely the fault of the initial script, which was once again hampered by set problems. Emily Mortimer’s newcomer castmate of Stab 3 was supposed to be the second killer, but Weinstein objected.

The trilogy wrapped up, DVD boxsets were set to be released, and the franchise concluded with a cruel inside joke and a lacklustre finale. If you’re particularly invested in the main characters, it’s a fine enough diversion, but Weinstein hangs over it, his fat, ugly shadow tainting what little was worth seeing.

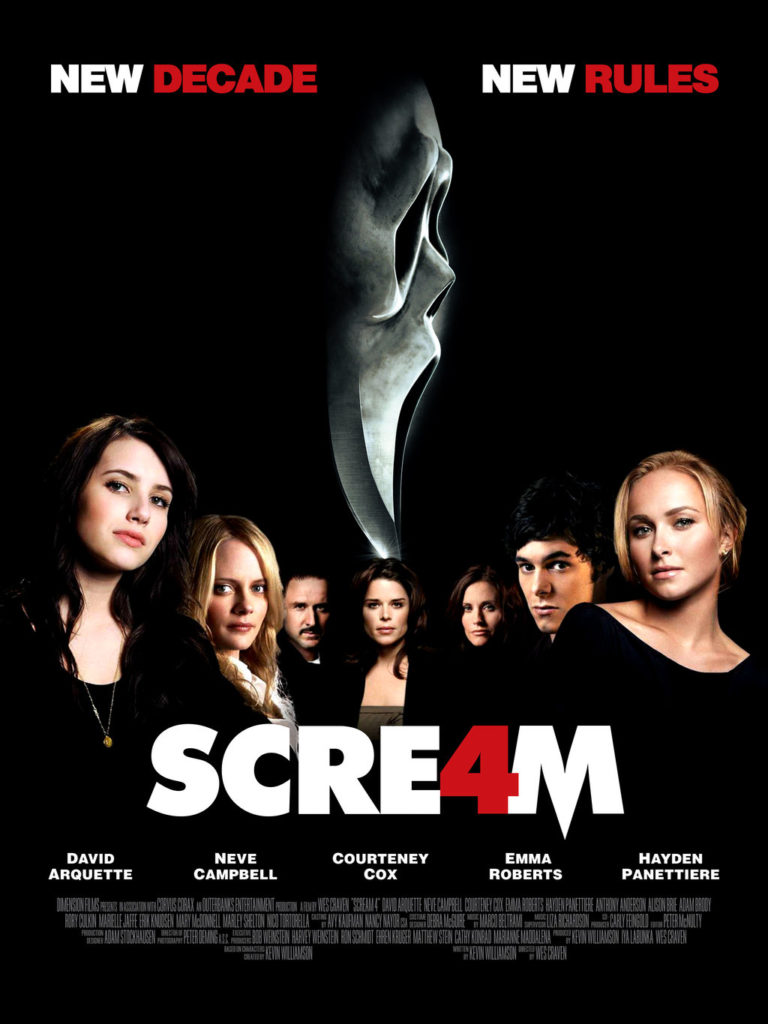

Williamson certainly saw potential in going forward, though it took eleven years for the bad taste of the last film to wash out. Scream 4 was released in 2011 with the three returning leads in tow, a new cast of young blood that includes Hayden Panettiere and Rory Culkin and further intrigue regarding Sydney’s family.

The meta jokes are increased tenfold here, with much more technology to ridicule including streaming. The Stab series is seven films in, probably well into their torture porn-imitation game. And though Sydney is a bonafide survivor with a book out, murders start to occur again.

If the family killer angle in part three was disappointing, it only kind of works here. It helps that Williamson is again working with two killers, the predictable Culkin and Sydney’s cousin (Emma Roberts) who is jealous of her fame. Roberts and Culkin are good, and there are a few surprises, but the familiarity that felt welcome in part two feels a little more alien now, with the redundancies in the script tired rather than intentional.

And, yet again, Williamson is too afraid to actually kill anyone that matters off. At this point, it’s become a necessity.

In 2015, with Craven and Williamson’s blessing, MTV premiered the television version of the film. It makes sense that Williamson would approve, as he never had an interest in quickly dispatching his cast. No more Sydney, instead we’re introduced to a new cast. And they’re surprisingly still just as likable as the previous gang, for the most part. Emma (Willa Fitzgerald) is in high school whose mother (Tracy Middendorf) has a complex history with a legendary deformed killer long thought dead.

In the pilot, Emma’s friend Audrey is subjected to public shaming when a video of her kissing a girl surfaces. It sounds like childish high school stuff, but it’s no more or less believable than the first film. Early in the show, the series’ Randy, now named Noah (John Karna), hosts a true-crime podcast where he often muses the way Randy used to, only his observations are up to date. And still quite funny. He, of course, wonders aloud about the challenges of doing a slasher film as a series, laughing the concept off, but it works surprisingly well.

The first two seasons of Scream are more entertaining, on average, than all of Scream 3 and even parts of the second. Back are fully drawn characters and a mystery worth getting invested in, even though it’s ultimately less satisfying. It’s a completely different animal; a spiritual successor that takes the very best elements of the franchise and modernises them. Having Craven on board until his untimely passing probably helped. But that doesn’t mean it’s not a shallower experience, and try though it may, you can’t possibly keep the same immediacy that a slasher environment can on television.

Finally free from Weinstein’s reach, the third season abandons the gang, and the producers. Queen Latifah and a group of new showrunners attempted a black version with Scream: Resurrection for six episodes. This never would have happened with Harvey Scissorhands at the front desk – the man who once balked at the idea of a mixed-race couple in Mimic as something America wasn’t ready for. Scream didn’t necessarily have race issues so much as a lack of any diversity. The black characters were stereotypes, even though at least one points out he’s a stereotype as early as the second entry. As a concept, it’s welcome. It’s just a shame that everything, from the killer’s identity and motive to the overall predictability and rote execution, feels so telegraphed. The shorter length of the season doesn’t leave much room for characters or even plot. You need a well-disciplined staff with a working knowledge of the genre, and preferably characters the audience doesn’t require exposition to understand, to pull that off well. Latifah and company’s attempt is noble, as far away from Weinstein as a project can get, but it’s just too flimsy. In the hands of someone like Jordan Peele, it’d be feasible. Here, even the killer’s name, Hook Man, sounds and feels very basic.

With a fifth film being shot as of press time, the fourth entry and television series do suggest hope for some kind of future worth revisiting. So long as Williamson can muster up the courage to actually off someone. Onscreen violence will forever be a sticky issue, and psychiatrists are often torn between party talking points. It’s just a shame a film that revitalized the genre after dormancy is haunted by a much more insidious spectre of the industry.

Final Ranking:

Scream

Scream 2

Scream: The Series (Season 1)

Scream 4

Scream: The Series (Season 2)

Scream: Resurrection (Season 3)

Scream 3

More Film Reviews:

The Ghost Station (2022) Film Review [FrightFest]

The Ghost Station is a 2022 South Korean horror thriller, written and directed by Yong-ki Jeong, with additional writing from Soyoung Lee, c, and Koji Shiraishi. Takahashi and Shiraishi are…

The Head Hunter (2018) Film Review – Revenge and Bloodshed

If like me, Straight Outta Kanto, you’re still suffering from Game of Thrones related withdrawal symptoms (and a little Season 8 PTSD) then 2018s “The Head Hunter” will staunch your…

Last Night In Soho Film Review (2021) – Music, Fashion And Mass-murder

With Last Night in Soho, Edgar Wright’s latest film, the British filmmaker continues down the path he’s carved with his 2017 ‘Baby Driver‘ – mixing different genres into an extremely…

Heavy Trip Film Review – Dark Comedy at its Best

If you’re a vegetarian and/or averse to the musical genre that is Post-Apocalyptic-Symphonic-Reindeer-Grinding-ScandoFinn-Metal then avert your eyes to the following review. 2018 Finnish shock-rock comedy Heavy Trip is just waiting to…

Dirty Cop No Donut (1999) Film Review – ACAB

Dirty Cop No Donut is a 1999 faux-shockumentary, written and directed by Tim Ritter. Mostly known for creating low-budget gore films, Tim is mostly known as the writer and director…

Deep Fear (2022) Film Review – I Did “Nazi” That Coming

Deep Fear is a 2022 French horror, directed by Grégory Beghin, who has made a name for himself as a TV actor, Grégory made his debut behind the camera with the 2020 comedy Losers…

![The Ghost Station (2022) Film Review [FrightFest]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/The-Ghost-Station10-365x180.jpg)