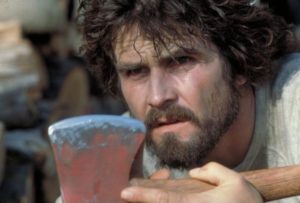

Just the facts ma’am. Or so one might expect the detective keeping vigil outside of the house in a rumpled raincoat to ask. He chews on his obligatory cigar and sips at his obligatory coffee that we will presume has gone cold. Nothing that the Lutz family does, whether it be George chopping firewood on his front lawn, or Cathy stalking her family priest to come and finally bless her new home, will slip past his sharp investigative powers. He’s on the case. Exactly what the case is, one can’t quite be sure. But he’s got his frumpy detective hat on, so he must mean business.

The Sgt. Gionfriddo subplot in The Amityville Horror (1979) does not ultimately go anywhere. His investigation is seemingly only based upon the fact that the detective thinks George looks an awful like the previous tenant of the home who murdered his family. Stakeout ensues, cigars get soggy, Styrofoam cups are emptied, then after a scene where he pointlessly shakes down a priest for absolutely no information, he will completely vanish from the movie after mumbling his final line: “Maybe I am only chasing shadows”. As if swallowed in one great gulp by the red herring that he has been chasing for about three abbreviated scenes, Gionfriddo and his hat will sink from sight, and we can get back to the important business of watching George chopping all that firewood.

For a movie famously touted as being based upon true events, The Amityville Horror‘s director, Stuart Rosenberg, paradoxically seems to be approaching the truth of his own film as a sceptic. Like the fruitless snooping of Gionfriddo over nothing but shadows, Rosenberg seems to be looking for facts that just aren’t there and, as a result, has thrown up his hands and instead constructed a film not so much haunted by ghosts, but by the spectres of a failing marriage, mid-life dissatisfaction and pained domesticity. Yes, walls will also bleed, but more importantly, so will pocketbooks.

As a result, the film will move towards its supernatural elements with the lethargy of a stepfather getting off the couch to tend to his step kids. While it may be compelled towards them out of a sense of obligation to the source material, it really doesn’t show any enthusiasm in committing to their maturation. Instead it will mope over the sort of details that slowly undermine a marriage, and then try to convince its audience to accept that these sometimes odd but almost always explicable events could be evidence of a haunting. They will have some problems with an insect infestation, money goes missing, the kids get injured during horseplay as well as Their plumbing backs up. There are some issues with the insulation in the house, leaving George perpetually cold. And then, with all the menace of allergy season, a nosy neighbour arrives on the porch with a six pack and a lip covered in snot. He’s popped by uninvited to introduce himself. Who doesn’t relate to the horror of such a thing?

Normally this would be more the kind of foe suited for a sit-com family to fend off, but in Rosenberg’s film, an unscheduled visit from this under dressed schlub next door is presented as yet another notch on his horror cred belt. At least as long as we suspend enough disbelief to conclude that this is the manifestation of centuries old Indian spirits seeping up from beneath the house; finally returning to a physical form as a runny nosed alcoholic who wants to talk shop about the New York Jets. When he mysteriously disappears from the porch before he can even share one of his Miller Lites, the jury has come back conclusively that this is Devil business. At least one must assume according to the ominous music that suddenly accompanies the mans vanishing act.

Meanwhile, as such terrors as theses continue to mount, George can’t shake a flu and his hair is suddenly in want of serious brushing. He hasn’t been to work for weeks. His eyes have turned to an exhausted shade of red either meant to evoke menace or looming unemployment. Beginning the film as a bearded and burly lumberjack of a man, he has now dwindled down into a flannel wearing husk in baby boy briefs: a fragment of his former self. And as the movie continues to chip at his ego, it becomes clear that the further he is scrubbed away, the more it seems that all that is washing off is his pretense of being a good husband and father. His tolerance for raising three children that are not his begins to fray, and he can’t keep up with the mortgage his wife had already reasonably warned him might be beyond their means. Not only is George not the man we thought he was, but he is not even the man he thought he was. And so off to that pile of lumber he skulks again, hoping to regain some of that lost virility by smashing the shit out of a bunch of wood.

With Rosenberg occasionally garnishing his film with traditional horror elements, it becomes natural to draw a direct link between the murder house that George and his family have moved into, and his growing anti-social behaviour. We have seen how the house’s windows light up like eyes at night, and how it exudes such an evil presence that it drives both priests and nuns to such convulsions of overacting, they either barf at the side of the road, or scream themselves blind. These are admittedly highly suspicious activities for a house to be engaged in. But maybe this is all little more than some supernatural camouflage for George’s all too ordinary decent into becoming a distant and abusive prick. More of a pragmatist than his Catholic wife, George himself even seems resistant to her insistence that something is evil about the home they have moved into. And when the wife of a co-worker talks about her sensitivity in contacting the spirit world, he seems mainly irritated at the thought that she might be offering such services to him.

For George, nearly all of the evidence of this haunting has a pretty clear bottom line. It has simply meant he will have to call a plumber, arrange for an exterminator, over pay on his heating bills because of that goddamned draft and find a babysitter who at least doesn’t get herself locked in a closet. Before we reach the climax of the film, one of the only true reckonings George seems to have in regards to the possibility of something supernatural happening here, is a moment where he hacks open a wall in his basement to find a hidden chamber beneath the stairs. As he peers into this room he has just uncovered, a mysterious vision comes to him. Staring back at him from one of walls that have been painted an all so subtle shade of crimson red, there will be a spectre of a floating head: his own… Or at least close enough. So even as George is being presented with something that can be safely considered beyond natural explanations, the implication still remains that whoever it is that is haunting this home, looks an awful lot like him.

Such a dreary affair as a man growing to despair over the bland miseries of his day to day life though is hardly what one imagines The Amityville Horror’s audience has come to see. Much like the Lutz’s, many in the audience may relate all too well to being overwhelmed with bills, the struggle of maintaining a happy family veneer, the inconvenience of children walking in on their lovemaking. For many, this trip to the theatre may be their monthly scheduled date night. Babysitters have been brought in to permit the occasion, and with the excessive two hour run time of the film, that leaves a lot of time for lots of American babysitters to find their own kinds of trouble with closets. So it would be understandable for many watching to be underwhelmed by a film promising horror to be presented with so much of what they have come to the theatre to escape.

But for some, those that maybe have bought into the ‘based on a true story’ hoopla, and maybe a little desperate to see such ordinary lives presented as something moderately extraordinary, the movie may find an audience more than willing to accept its molasses slow chills after all. It definitely allows for a better narrative in our lives when we can view the details of an unfulfilling existence as being something a little more exotic, even if it isn’t really earned. To imagine the clogged toilet that is coughing up shit in your bathroom, as instead filling with a demonic sludge. Or that the eyes glimpsed outside of a darkened window, are not evidence of a stray cat, but are quite obviously those of an imaginary friend dreamt up by a daughter in consort with the dark side. Additionally, when George loses a wad of cash from the living room, it is not between the cushions of the couch he should be looking, but instead he should be screaming in an empty room at the unseen perpetrator of this other worldly prank to give it back. The Amityville Horror, in this way, may have almost stumbled upon an audience that will be eager to become complicit in forgiving the increasingly lousy actions of George, not only because maybe they are married to a George themselves, but its just so much more fun to view the whole yawning middle class of America as under the thumb of a perpetual haunting. Maybe they too will one day be able to abandon their lives behind them, and sign a book deal. It can happen to anyone!

Almost as a surrogate to this sort of audience member, Cathy Lutz herself seems equally eager to accept the ‘haunted husband’ version of this narrative. Plagued by a nightmare of George murdering her children, her response to these subconscious concerns of hers that bubble up in her sleep, will not be to find the original sin as something that has been laying dormant inside of her husband. Not at all. It is instead to seek out the help of the Catholic church in getting her home blessed. Because this is what is to blame here. If only she could just wrangle Father Rod Steiger away from his damp eyed, knuckle chewing soliloquy’s on the horrors of house flies, and get around to dashing a little of that holy water at the threshold of their bedroom, maybe her husband would be free to return to normal. It is the ghosts, after all, that are keeping him from bed during those long cold sleepless night where he tirelessly feeds wood into his fireplace, unable to shake the chill of mediocrity that has seeped into his bones. It is the ghosts that caused him to slap her to the ground when she dared interfere with him tending to this fire. It is the ghosts, and not George’s personal shortcomings, which compel him to spend afternoons standing in the rain, chopping hilarious amounts of firewood as if it is the last lingering evidence of his diminished virility. It just has to be the ghosts, because then she can always choose to move away from the home and whatever haunts it, presumably also leaving behind whatever fondness George has for fondling that axe handle.

But it is a hopeless belief that she holds onto. Even as the film begins to become a little more outwardly gregarious with evidence of an actual haunting, setting off all of its supernatural Roman Candles at once during its climax, there is a moment which seems to speak louder than the blood dripping from the walls, or the visions of demon pigs in windows. George will go barrelling into the home with his axe. From the look on his face, this appears to be the moment when both the malice of the home and the malice in George’s heart have merged. The house creaks and teeters with the force of a thousand ghost story cliché’s as George beings to chop down the bathroom door his step children are hiding behind. Emerging from the shadows, Cathy jumps upon George’s back to stop him, but he quickly swats her to the floor. And then, as he stares down at her, axe in hand, what he sees is a clear tell towards what the true nature of George’s demons. Staring up at him is not the youthful Margot Kidder he has married, but instead, is Margot Kidder webbed in prosthetic make up. She is greyed, wrinkled and aged. This is a vision of what awaits George if he dares to maintain his vows of til death do you part to its more traditional end. And so this will be the moment, staring at this phantom, that George will bring the axe down.

Whether or not he misses is besides the point. Whether or not he comes to his senses once his wife regains her youthful flush, and can now act the proper hero by dragging his family out of from the home, can hardly be absolution for the horrors that likely still await this family. What should be frightening is not the house that is spitting hell fire behind them as George speeds down the road with his wife and kids and dog by his side. It is that he will be the one driving them away to safety as the tail lights disappear into the darkness… If only Detective Gionfriddo hadn’t skulked off to be forever lost in those shadows he was chasing.

More Film Reviews

Seagull (2019) is an oddball revenge story centred on family drama, secrets, and spite. After 8 years of eking out survival on a beach, Rose returns home and the full… “The relationship between the Dolans and the Lomacks turns sour when one of them leases their land to a natural gas company. The drilling has disastrous results as it unleashes… Unspeakable: Beyond the Wall of Sleep is a 2024 horror film, written and Directed by Chad Ferrin. The film is an adaptation of H.P. Lovecraft’s short story Beyond The Wall… The world of short films has always been an exciting one for those willing to embrace the format – both in giving insight into future filmmakers and offering short narrative… If like me, Straight Outta Kanto, you’re still suffering from Game of Thrones related withdrawal symptoms (and a little Season 8 PTSD) then 2018s “The Head Hunter” will staunch your… Best known as the author of the novel Audition, which inspired the popular film of the same name, Ryû Murakami is a prolific novelist who has a large body of…Seagull (2019) Film Review – Time For Extraordinary Revenge

Unearth (2021) Film Review – Fracking Despair

Unspeakable: Beyond the Wall of Sleep (2024) Film Review – An Inventive Yet Deferential Reimagining

Cult Affairs Short Film Review – Devil in the Details

The Head Hunter (2018) Film Review – Revenge and Bloodshed

Tokyo Decadence (1992) Film Review – The Decadence of Man