“It’s not my fault that I’m Japanese… yet it’s my greatest sin that I am.”

-The Human Condition I: No Greater Love (1959)

During the Second World War, Unit 731 of the Imperial Japanese Army was stationed in Manchuria. Officially known as the Epidemic Prevention and Water Purification Department of the Kwantung Army, the unit carried out research into biological and chemical warfare. In his 1993 book Factories of Death, Sheldon H. Harris estimates the number of people tortured and killed to that end at 200,000. Others put the number somewhere north of half a million. Those who survived were left traumatised, mutilated, and disfigured. Eventually, twelve researchers were arrested by the Red Army and tried at the Khabarovsk war crime trials, only to be granted immunity and paid stipends by the United States. In 1988, Shaw Brothers alumnus Mou Tun-fei released Men Behind the Sun, a highly controversial dramatization of Unit 731’s crimes. Due to its extreme violence, both Japanese and Hong Kong critics heavily questioned the educational value of the film. Twenty years later, Russian director Andrey Iskanov continued the controversial trend with his film, Philosophy of a Knife.

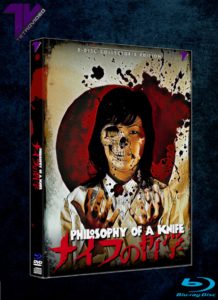

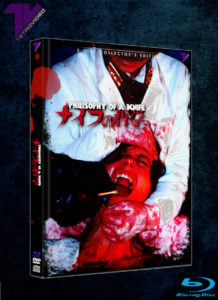

TetroVideo’s release (cover A)

Split into two parts and described as “an artistic representation of factual events”, Philosophy of a Knife was originally screened as part of the 2008 Sitges Film Festival. Having previously received DVD releases from TLA Releasing and co-producer Unearthed Films, this year the film receives an ultra-limited edition from TetroVideo, purveyors of all things extreme. The release includes a DVD and a Blu-ray, as well as a CD of Alexander Shevchenko’s score. Clocking in at almost four and a half hours, Philosophy of a Knife requires patience. The resulting balancing act between historical footage, interviews, and Iskanov’s frequent forays into the extreme is unsteady at best, and downright amateurish at worst. The opening sequence features Japanese soldiers peering intensely at snowy landscapes and crunching squeaky-shoed through the tundra. (Sound effects are consistently unconvincing.) This pointless padding foreshadows much of what is to come.

Iskanov’s dramatizations of various war crimes share screentime with clips from an interview and black-and-white archival footage. The interviewee is Anatoliy Protasov, a former doctor and military translator. His relevance is questionable. As one reviewer puts it, “he once picked mushrooms near Unit 731”. Dryly narrated by Stephen Tipton, the historical footage provides context that is readily available to anyone who has even a vague interest in the history of Unit 731 and Japan’s historic war crimes. The film also spends time criticising the Soviet Union, and Communism generally. While Unit 731’s crimes are specifically targeted and depicted, Iskanov also highlights human experimentation allegedly carried out by the Soviets concurrently. Archival footage of conjoined twins, surgical procedures, and women exercising is presented without context.

Alongside interpretations of actual experiments carried out by Unit 731, Philosophy of a Knife also offers a fictional narrative. The nonsense plot concerns the so-called Favourite Girl (Elena Probatova), a young Russian woman favoured by a Japanese officer. The electronic score softens during their scenes; a hideous tragic romance suggests an insidious attempt to garner sympathy for the fascist. In many ways, Iskanov’s methods mirror the oft-criticised tactics employed by those who produce Holocaust Cinema. In Schindler’s List (1993), Spielberg invites us not to empathise with six million murdered Jews, but with one little girl in a red coat. Here, Iskanov does not presume our sympathy with the Chinese or the Communists. Instead, he focuses on the Russian victims and, in partiular, one beautiful white girl.

TetroVideo’s release (cover B)

While there is a debate to be had regarding the nature of violence in film – how the camera positions us as witnesses, as voyeurs – extreme violence certainly has its place, especially in stories like these. It can be argued that the only way for fiction to truly capture the inhumanity of crimes such as those committed by Unit 731 is to depict them as explicitly as possible. When he made Cannibal Holocaust (1980), in order to expose and condemn the savagery of colonisation and the continuing exploitation of Indigenous groups, Ruggero Deodato exploited the Indigenous performers. In Men Behind the Sun, Mou Tun-Fei’s niece almost suffered frostbite, and the body of a child killed in an accident was used in a vivisection sequence. Both directors received criticism to varying degrees of validity. Both, for example, were criticised for violence against animals, though only Deodato’s accusations carried weight. To the discerning viewer, however, their films’ intentions are clear.

Andrey Iskanov can claim no such intentions. Not only is Philosophy of a Knife poorly structured and overlong as a documentary, as a horror film, but it also lacks efficient emotional weight. Poor performances and shoddy effects (visual and sound) result in exploitation of the laziest variety. Obviously real dead bodies make obviously fake ones even more noticeable. Iskanov employs techniques like deep focus to heighten the tension, but his attempts are undercut by laughable staging. Bodies are bludgeoned to bits in the background, while a Japanese nurse plays a mouth harp in the fore. The film is arguably too stylised to be scary – the style too forced and clumsy to be successful. A pregnant woman’s forced caesarean approaches the horror Iskanov desires, but the repeated intense zooms on drawings of surgical tools deaden the effect. The fetus is visibly plastic, and Iskanov’s reveal of a photograph of the real crime puts his dramatization to shame.

Like many extreme horror films, Philosophy of a Knife has attained something of a mythic quality since its release. There was perhaps no chance of it living up to its reputation. Criticisms levied at Men Behind the Sun might be better directed towards Iskanov and Philosophy of a Knife. At no point does the film attempt to justify its existence as anything other than Iskanov’s passion project (he directs, writes, shoots, edits, and co-produces). We are promised horrors, real and reconstructed. What we receive is a relentless mess of torture and tedium. For a film that explores such a dark part of history and, therefore, depicts extreme crimes against humanity, Philosophy of a Knife is a dull blade in desperate need of sharpening.

Philosophy of a Knife is available now. Grimoire of Horror thanks TetroVideo for providing a copy of the film in exchange for an honest review.

Special Features

- 150 numbered copies (300 across both covers)

- Mediabook

- Blu-ray

- DVD

- CD Soundtrack

- 40-page booklet

- Slipcover (limited to pre-order customers)

- Russian/English language – English, French, and Italian subtitles

More Extreme Cinema Reviews

If You Love Horror Books, You NEED to Get on Godless! Let’s get one thing straight: Godless.com is NOT a satanic cult! It has nothing to do with religion of… The early days of film exploration were pretty wild, with the advent of VHS and early online access creating a community of people pushing filth. Consequently, certain films became a… I’m sure in one way or another, everyone is at least somewhat familiar with the works of Edgar Allen Poe. From the plethora of film adaptations as well as their… August Underground’s Penance is a 2007 extreme found footage horror film, written and directed by Fred Vogel, with additional writing from Allen Peters and Cristie Whiles. The film is the… Johanna is just twenty years old but struggling with her boring and aimless existence. Disturbing visions start the day she gets fired from her job. Soon Johanna is carried off… Disclaimer: Film contains animal abuse Calamity of Snakes (Ren she da zhan) is a 1983 Hong Kong/Taiwanese CAT III action horror, written and directed by Chi Chang with additional writing…Godless.com: The Best Place to Buy Indie Horror Books!

Mai-Chan’s Daily Life (2014) Film Review – Extreme Graphic Depravity

Echoes from the Grave Film Review – Modern Retellings of the Classic Works of Poe

August Underground’s Penance (2007) Film Review – Rocking Round The Christmas Tree

Dark Circus (2016) Film Review – The Goths Are Alright

Calamity of Snakes (1983) Film Review – Savage Serpent Snuff

Isabelle is a writer from the UK who enjoys alternative manga and horror films. When not writing, you can probably find Isabelle buying books or obsessing over Martin and Lewis.