Do something for me first, before you start reading. Put on the soundtrack to Transistor – the developers, Supergiant Games kindly uploaded it for you to listen to. I’m sat here typing this article now with the music playing. Take the time and get into the mood for a world ending…

Something else. If you want to learn to hate something that you loved, learn about it formally. Sit in an organized setting and have all the joy and wonder sucked out from it, its marrow stripped clean and left a specter of its former self. All in pursuit of an unneeded extrapolation. I did this for five years and learnt to hate film. It was a slow process to reverse. So naturally I’m going to take a film that I adore. And I’m going to look at it, from angles I had not before and see what I can learn now. All with a hope that I’ll still love it at the end.

Class is now in session.

Death and Taxes.

If taxes have a price, then all that is left is to determine the manner in which they are to be paid. The idiom then tells us that there are two things in life that cannot be avoided, the other; death. Create an An-Cap society and you’ll prevent the idiom from ever becoming an axiom which I’m sure will be of comfort to someone, sat silently, their right eye twitching as the glare of a monitor burns through their retina during another 3AM session of internet deployed vitriol. How about the rest of us cheer ourselves with the thought of pestilence and occurrences transpiring on the level of an apocalyptic, extinction event? Let us look at the Black Death, the plague that swept across continents and killed millions, by estimates 75 to 100 million in the 14th Century. Let us also bask in the glow of nuclear fire, our pupils set ablaze with a white light while our backs chilled in the same instant by Cold War paranoia. Let us look at “Det sjunde inseglet” – Eng. The Seventh Seal.

1. And when he had opened the seventh seal, there was silence in heaven about the space of half an hour. 2. And I saw the seven angels which stood before God; and to them were given seven trumpets.

Revelation 8:1-2 [KJV Edition]

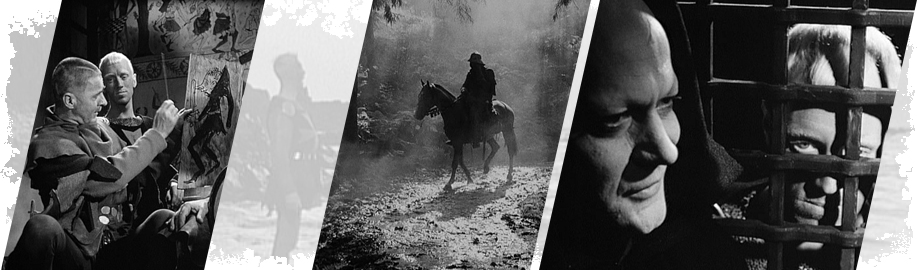

The Seventh Seal is a 1957 Swedish film both written and directed by Ingmar Bergman. It would do it something of an injustice to try and bust it down to a specific genre as though some sort of awkward clump of rock in a quarry. At its most basic, it tells the story of a knight returning to his native Sweden from the Crusades. Death comes for him and the knight, in a crisis of faith seeks to delay Death by challenging him to a game of chess. It is around the moves of this game that the knight questions his faith, seeking to restore it and fill the (physical and spiritual) silence on Earth that he now experiences.

The passage from the Book of Revelation that opens and closes the film refers to the end of the world, angels heralding calamities that would rend the Earth before the day of judgement. A situation that many at the time of the 14th Century, during the Black Death, were convinced was occurring. When all bets are off and there is little but to make peace with yourself and a higher power then it’s no surprise that the individual will look inwards, what they may find however is something else entirely. Our broken knight; Antonius Block – played by Max von Sydow, will have, during the course of the Crusades seen and have carried out actions far beyond the measure that any one of us could reasonably comprehend. It would be no surprise that this would trigger a crisis of faith, if they were to return after ten years to see their home laid to waste by a relentless pestilence that was to torment the continent repeatedly for hundreds of years, even up to the 19th Century.

For some, the Black Death was seen as a punishment from the Heavens. The corruption of the people and their immorality being held to account. If a tax is not to be paid in money then what else can it be but actions or a very life? Indeed, during the film, a procession of what became known as the Flagellates moves through a village Block finds himself and his squire; Jöns – Gunnar Björnstrand in. The Flagellates would move as one, rending their flesh with whips while chanting psalms in an act of contrition. They chose to pay penance in their own way for perceived slights against God. Their very existence though was regarded as a challenge to the Church’s authority and as a movement were dealt with swiftly and harshly – declared heresy and suppressed to the point of Inquisitorial elimination. It was but one example of the hysteria that was running rampant through the continent with a vigor comparable to that of the plague.

Block however endeavors to if not cheat Death, then to somehow manage a stay of execution. It is for the reason of his crisis of faith, a deep fear of abandonment by God that acts as his central motivation and leads us on a tour of mid-twentieth century fears via the concerns of the fourteenth century. What is interesting is how Block goes through stages of evaluation, reasoning and bargaining – each creating new crises to accompany them. He seeks comfort and confirmation of God’s existence by challenging a woman, sentenced to death for consorting with Satan to summon him (Satan) so that Block can gain the answers he seeks – the notion of one existing so the other must also. All Block finds is a terrified, young woman who he seeks to ease the passing of – she is incapable of providing what he wants and needs, but through that act of mercy, allowing her to face her execution without pain, gives rise to faint stirrings of a realization.

It is through works and faith that an individual can find salvation, at least within the Catholic Church of which prior to Martin Luther and the Reformation, European Christendom would have been. Block’s journey leads him to the realization that he will only find peace within himself when he has actively sought peace – works and faith. Through an act of goodness Block believes he will find the salvation, connection and perhaps absolution he so desperately seeks. With Death waiting, Block must play not only for time and his own peace, but his soul. We’ll get back to this act of goodness but first I want to look at Block’s journey in a more ordered fashion.

Blessing in disguise.

We start on the Swedish coast, The knight – Block reclining. Rinsing his face in the waters of the sea he is thankful to be home from the crusades. Turning he looks to see Death. His time has come, Death having been at his side for quite some time already. Not quite ready however to leave this mortal coil:

“My flesh is afraid, but I am not.”

The knight stalls Death with the offer of playing chess for his life. Death is quietly amused and puzzled that the knight would know of his interest in the game. It is worth mentioning, as Block comments, that Death has been represented as being fond of the game and has been featured in art on numerous occasions. Perhaps most fittingly in this case, within the painting: Döden spelar schack Eng. Death playing chess, painted in the period 1480-1490 by the Swedish painter Albertus Immenhusen/Albertus Pictor. We’ll be looking at the effect The Black Death had on the arts – one of its myriad legacies, but for now, back to the story.

With Death agreeing to the terms of the game the two play. The chess game doesn’t so much as provide a structure to the film, moves announcing dramatic beats but instead functions more as punctuation. It underlines or emphasizes points within the story, taking place where Block has the time free to play. The world keeps on turning, regardless of their game which while means the film misses out on being able to use the chess game to raise tensions, allows it to instead; better realize the world that the story is taking place within.

The game halted for now, Block and his squire Jöns set off inland. Seeking directions Jöns finds the body of a man, overlooking the sea and accompanied by his dog, consumed by the plague:

“Did he show you the way?

-Not exactly.

What did he say?

-Nothing.

Was he mute?

-No, milord… He was most eloquent.”

The dynamics between the knight and the squire have been clearly established. Jöns is a smartarse, but he’s no fool. There is a temptation from this point to see Jöns as regarding himself as a dead man walking, however one without fear.

At this point we shift to following a theatre troop. They wake up, greet the day and Jof – Nils Poppe has a vision of the Virgin Mary. His wife regards him as a fool, not with malice, just the quiet humour of someone that truly loves him, despite his foibles. They play with their infant child (Michael) – an island of tranquility within a maelstrom of pestilence. We have found the heart and soul of this world in this small family. The world however is going to keep on turning and churning, inevitably to affect our new friends.

Our previously mentioned medieval painter; Albertus Pictor makes an appearance. Jöns talks with the man as he works and they discuss the plague – Pictor delighting in imparting the ghoulish details and the discomfort it causes in Jöns, its origins and the Flagellants – their mention shaking Jöns in a way we would perhaps not expect, a quiet nod to other potential horrors the man has witnessed while in and on the journey to and from the Holy Land.

“Lashing each other?

-Yes, it’s a horrible sight. You feel like hiding when they pass.

Give me a gin. I’ve had nothing but water. I feel as thirsty as a desert camel.

-Scared after all?”

We rejoin Block as he stands in front of a crucifix. He walks to the confessional and seeks to unburden his soul but must admit:

“I want to confess as best I can… but my heart is a void. The void is a mirror. I see my face… and feel loathing and horror. My indifference to men has shut me out. I live now in a world of ghosts…”

The cleric challenges him that he does not want to die. Block disagrees, claiming that he is waiting for knowledge, a guarantee of life everlasting, the existence of God. Block talks of the limitations of man’s senses and the difficulty of believing in something larger than the self when believing in the self is challenge enough.

“Why can I not kill God within me? Why does He go on living in a painful, humiliating way?”

The cleric is revealed to be Death, Block continues to bare his innermost fears, unaware of the identity of his confessor. He reveals his plan; one significant action to give meaning to a hollow life, to restore a sense of self and perhaps by extension, to restore his faith. To do this he must keep Death playing their game of chess. Revealing how he intends to beat Death the identity of the confessor is revealed. Block has a moment of realization that while he lives, he can still do something, no matter if Death now knows his strategy. With the will to succeed and the found ability to do so, Block steels himself to continue.

Block returns to Jöns and the painter, Jöns protesting the futility and unpleasantness of the crusades and perhaps life itself. Jöns finds relief in the ridiculousness of it all and deigns to live for himself and the immediate pleasures of the flesh while it lasts, to Block’s disapproval. Leaving, they encounter a young woman held in the stocks, due for execution for consorting with the Devil. Block questions her as to the validity of her claims – if the Devil exists, then so must God. Another cleric claims that she is the source of the plague. The woman appears catatonic before breaking into a murmuring cry as the men leave.

More Reviews:

Fright Night for Real: Jerry Dandrige vs. Jerry the Vampire

Nowadays, it is hard to find a person among horror buffs or moviegoers in general who has never heard of the title Fright Night (however, I am afraid that there…

Crisalida (2023) Film Review – Pushing the Limits of Experimental Creativity

Crisalida (2023) [The Chrysalis] is a Spanish extreme gore horror film, written and directed by Mikel Balerdi. Well-known in the extreme cinema community, Mikel is notorious for pushing the boundaries…

Faceless (2021) Film Review – Who Are You Really?

“A disoriented and frightened man awakens in a hospital room to discover he’s the recipient of a full face transplant. Plagued by weird flashbacks, no memory, and no visitors, he…

2LDK (2003) Film Review – Killer Co-habitation in the Tiny Rooms of Tokyo

Having a roommate can be hard. Whether it’s disrespect of the kitchen cleaning rules or failing to remember how thin the average bedroom wall is, living with another person is…

Looky-loo (2024) Film Review – Through the Eyes of A Killer [Unnamed Footage Festival 7]

Almost entirely free of dialogue, Looky-loo (2024) gives viewers the view from a killer’s own eyes as he stalks and plans multiple murders. The nameless killer, gains confidence with each…

V/H/S/85 (2023) Film Review – Be Kind, Rewind

If you are a lifelong fan of horror, then you know full well that endless sequels and remakes are just a part of the game when it comes to film….

![Looky-loo (2024) Film Review – Through the Eyes of A Killer [Unnamed Footage Festival 7]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Look-Loo-2023-review-365x180.jpg)