Nowadays, it is hard to find a person among horror buffs or moviegoers in general who has never heard of the title Fright Night (however, I am afraid that there would be a few die-hard Twilight fans). In most cases, people recognise the phrase either as “that old horror film from the 1980s” which gained a strong cult following or as “that popular remake” with David Tennant in the supporting role. Regardless of which particular movie they have in mind, the main story behind the vague but interesting title is obvious to anyone: a vulnerable teenager with the help of a vampire-killer-from-cable-TV confronts a tough as nails vampire in order to rescue his girlfriend. The following comparative analysis aims to juxtapose the original and the remake of Fright Night in order to evaluate which of the two pictures can be considered as a better made horror film.

Fright Night (1985)

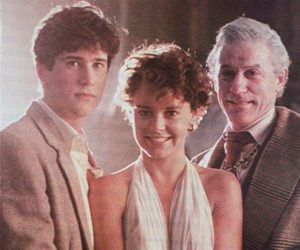

Let us firstly start with the original film. The whole idea of a teenager finding out that his next-door neighbour is a vampire and seeking help from a local TV host was devised by Tom Holland (screenwriter of Psycho II, Class of 1984, and Cloak & Dagger) who allegedly wrote the screenplay rolling on the floor laughing. Needless to say, such a story combined with proper casting and meticulously devised practical effects became much more successful (both critically and financially) than originally anticipated by its creators[1]. However, does the movie stand the test of time?

The very first shot of the film is a full moon with the distant sound of howling, which in itself is quite confusing and funny at the same time, considering the fact that we are not watching Dracula with Bela Lugosi. Yet, as the camera slowly turns to provide an overview of a standard middle-class neighbourhood, we hear dialogue off camera which strikingly resembles the conversation between an infatuated Harker and a possessed Mina from the 1931 film. Only when the camera sneaks into a room of Charley Brewster, the main protagonist of the film, do we see that Dracula’s original scene is a B-class re-enactment done very much in the Hammer style. Nevertheless, Charley is not interested in watching his favourite late show Fright Night because he is too busy trying to go all the way with his girlfriend Amy. Yet, even this activity is interrupted (not surprisingly as far as horror tropes are concerned) when Charley notices two guys outside carrying a coffin… Later, while playing peeping Tom out of boredom, he accidentally spots the man next-door, Jerry Dandrige, making out with a random lady (who certainly screams not out of pleasure in the end). After hearing about a series of recent murders, the teenager quickly connects the dots and, throughout the majority of the film, we see him trying to convince everybody around that his new neighbour is actually a vampire.

Unlike other horror films of the 1980s, Fright Night did not struggle to be original and innovative through shocking effects and numerous jump scares, but by being creative and playful with the whole conventionalised vampire mythology. “Fright Night is both an homage to the vampire genre and also a revitalisation of it,” said Chris Sarandon in one of the interviews[2] and this is very much the case. First of all, we have Charley Brewster, an average teenager who is a mega horror fan and all of a sudden horror turns out to be real for him in form of Jerry Dandrige, a modern-day Dracula who can fit himself into any historical period. Between these two opposing characters is Peter Vincent, a used-up vampire hunting hero from all those countless old movies who has to come to terms that vampires really exist and uses his screen experience to defeat the forces of evil. These three characters and their relationships constitute the core of the picture, and by stating the core, I mean the excessive use of many attributes and elements known to the horror genre.

For instance, Charley is a distressed main protagonist, who in order to protect himself from vampire attacks is using any means available such as crosses, garlic, candles, and other Christian memorabilia. On the other hand, there is Jerry who only differs from Dracula with a swaggering charm and lack of a cape; other than that, he is capable of changing into a bat and fog, sleeps in a coffin, and avoids sunlight. Whereas Peter Vincent has his toolkit full of props so as to detect (through holy water or mirror reflection) and kill (by wooden stakes and revolver with silver bullets) creatures of the night. In this way, all those elements are not only crammed into one picture to provide empty references, but they serve as an intertextual play with overused conventions. Nowadays, it may seem funny to watch Hammer classics where all the rules of how to fight vampires are unbreakable and Fright Night does not attempt to parody this suspension of disbelief, but provides the context in which these rules fail to work properly. “You have to have faith for this to work on me, Mr Vincent,” says Jerry laughingly crushing his cross; or, when getting rid of Jerry’s minion, Billy Cole, it takes all of Vincent’s silver bullets to kill him; yet after the successful staking of Evil Ed, Peter triumphantly exclaims: “So far, everything has been like it was in the movies.”

In addition to this, the film is not simply Abbot & Costello Meet Dracula all over again, but strives to play it serious for most of the time. This is done through creating a distinct, dense feeling of the 1980s. Jerry Dandrige is not an outdated count from Transylvania but a chad playboy, Charley is a standard everyman having a relationship with Amy and a twisted friendship with psychopathic Ed, and Peter is a relic from the 1950s who loses his job because “all [the viewers] want are demented madmen running around in ski masks hacking up young virgins.” Moreover, such things as Jerry’s relation with servant Billy can be perceived as quite homoerotic, whereas the sensual contamination of Amy strongly denotes the contraction of AIDS. All of this is combined with the film’s upbeat soundtrack which is commenting on the storyline. For instance, when Jerry is chasing Charley and Amy we can hear “Armies of the night they’re coming, they’re coming,” or during the seduction of Amy at the disco the music switches at least three times to indicate changes in the characters’ mood: Good Man in a Bad Time/ I Give it Up/ Beast Inside of You.

To sum up, Fright Night from 1985 can contemporarily be perceived as a horror classic by borrowing handfuls of old stuff and assembling it together with a witty story and memorable characters. Starting from Jerry’s first transformation and finishing on the epic showdown at his dilapidated house, Fright Night still manages to entertain and provide a few unforced scares. On a side note, it seems even more surprising to me that Fright Night II (1987) was not as successful as the first part considering the fact that it copied and pasted the original’s entire formula.

Fright Night (2011)

In the modern period of countless film remakes (especially within the horror domain) it was inevitable to see Fright Night 1985 being remade. However, is Fright Night 2011 only an attempt to dust off and capitalise on the old franchise? Or maybe it stands as a superior picture with its reinvented story and casts the original back into the shadows?

The opening sequence already lets us know that this film is completely different in tone. Instead of a slow building of the tension, we have fast-paced action almost immediately as some random teenager and his family are being slaughtered by “Jerry the Vampire” (for some unknown reason, the villain’s surname is omitted). Hence, contrary to the original which was universal in context, this remake domesticates Fright Night further by turning it into a solely American-specific adventure. For example, the setting was changed to a small suburban area outside of Las Vegas (possibly to amplify the feeling of isolation), Charley Brewster has an attractive mother and a girlfriend who looks like a supermodel, whereas Jerry is basically a muscular thug in a tank top. In other words, we get typical Hollywood features– handsome men, hot women, and Vegas baby!

On the other hand, the main change in the narrative was provided by a shift in the characters’ perspective. Charley is no longer trying to convince people about Jerry, but instead we see him trying to be convinced, which renders the comedic aspects of the film unentertaining. In fact, the picture’s humour does not rely on horror elements or character interactions at all, but on the constant usage of the word fuck. When there is something going wrong, all the characters just have to say this magic word which is supposed to evoke a comic relief, yet this gimmick fails miserably.

As far as playing with vampire conventions is concerned, the film scraps the use of familiar attributes to primarily focus on something that was a 10-second-long joke in the original film. Namely, the idea of not inviting the vampire into one’s own house. This motif drags on for the first half of the movie only to end with Jerry blowing up Charley’s house. Other things that played a vital role in the 1985 production are thrown in here at random, like burning crosses, silver bullets, and a crossbow… not serving any purpose at all.

When focusing on the characters, the three central heroes of the original are squandered here. Charley Brewster is no longer an ordinary teen but a geek hanging out only with cool colleagues. Furthermore, he is also such a weak protagonist that he is saved from certain death at least on two occasions by his girlfriend and his mother. Additionally, his relationship with Evil Ed is even more confusing than in the original. Original Ed was a barely likeable psycho but sort of a friend at the same time, whereas in the remake, he is the ultimate nerd who becomes Jerry’s slave in the first ten minutes of the film. Speaking of Jerry, he is nothing more than your run-of-the-mill, dark, good looking, yet completely devoid of Dandrige’s magnetism vampire with superpowers equalling the Avengers. You can run him over, stake him multiple times, set him on fire, and he will still survive. Nevertheless, Peter Vincent seems the most disappointing part of the film. He underwent an update from a burnt-out TV host to a successful Vegas showman who is constantly wasted and tired of fame. Of course, David Tennant managed to sell the forced humour, but his Peter Vincent feels completely irrelevant. While original Peter was a coward who needed a refuelling of faith to make things right, Tennant’s character was so badly written that he was even provided with a childhood back-story to make him more personally involved in the film’s finale. In spite of this measure, he still does not leave much of an impact on the story.

In terms of the finale, and this is only my personal observation, it strikingly resembles (if not using the word “copies”) the ending of John Carpenter’s Vampires (1998). That is to say, the two protagonist find themselves outgunned in the middle of nowhere and have to defeat the ultimate bad guy along with the unexpected army of minions he has created. In this final confrontation we do not get memorable quotes like “You’re out of time, Mr Dandrige,” or an amazing sequence of Dandrige’s annihilation during which he literally explodes. Instead, the remake throws us some pretty outrageous CGI and hand-to-hand combat between Charley and Jerry. In the end, we see Charley and Amy finally consummating their relationship in Vincent’s apartment, which is an embarrassing conclusion rather than properly done closure when contrasted with the original’s ending of Charley and Amy getting into bed and two gleaming red eyes watching them from a dark window next door.

Taking everything into consideration, Fright Night 2011 seems like a fan film based on the original movie. It is to some degree enjoyable, but only to those who have previous knowledge of the original. In this way, knowing what is familiar and how it became reinvented becomes enjoyable. Otherwise, the remake may be regarded as some TV special with weak special effects, unconvincing acting, and artificial dialogue straight from computer games. Instead of struggling to be something different from Fright Night 1985, the remake constantly refers to its father-picture, transforming itself into an homage to an homage to classic horror films. In consequence, it definitely does not work as a horror film. Once again, the classic outweighs the remake.

References

Fright Night. 1985. Dir. Tom Holland. USA. Columbia Pictures.

Fright Night. 2011. Dir. Craig Gillespie. USA. Dreamworks Pictures.

Endnotes

[1] Fright Night earned $25 million (without inflation calculated) against the budget of $7 million, becoming the second highest grossing horror film of 1985 (topped only by Nightmare on Elm Street 2) (www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=frightnight.htm).

[2] Chris Sarandon’s quote: www.youtube.com/watch?v=gH2MJxX8Jcg.

More Film Reivews:

Mosquito State (2020) Film Review – A Muddled Metaphorical Treatise on Bloodsuckers

Shudder, as a platform for exclusive releases, has been an enjoyable and interesting experience. Being able to curate directly for fans of the genre has allowed an impressive range of…

Hell Night Film Review – A Hybrid of Slashers and Haunted Houses

Being mostly an American tradition, fraternities seem to be full of real life horror stories due to the harsh hazing rituals regularly to new pledges. These organisations seem to be…

The Last Horror Movie (2003) Film Review – A Character Study in Murder

The Last Horror Movie is a 2003 British found footage horror mockumentary, written by James Handel and directed by Julian Richards. Beginning his career with the award-winning shorts Pirates (1987),…

The Beta Test (2021) Film Review – Navigating Hollywood’s Seedy Underbelly

A mysterious envelope promising an anonymous sexual encounter tempts a Hollywood agent weeks before his marriage, and following through on it throws his life off the rails in ways that…

Nightmare Radio: The Night Stalker (2023) Film Review – Radio Gaga

Nightmare Radio, Where Horror Stories Never End From the producers of The 100 Candles Game (2020) and The Red Book Ritual (2022), Nightmare Radio: The Night Stalker (2023) is a collection…

Top 15 Pseduo-Snuff Films – Diamonds In The Snuff

The generally agreed definition of a snuff film is a real (not staged) filmed murder. In some cases, it is viewed for the purpose of arousal. However, this is somewhat…

Oliver Ebisuno is a guy who likes watching (and reviewing) Asian movies. I have my own blog, Watching Asia Film Reviews, and I’m also submitting articles as well as editorials to MyDramaList, Kayo Kyoku Plus, and Asian Film Fans.