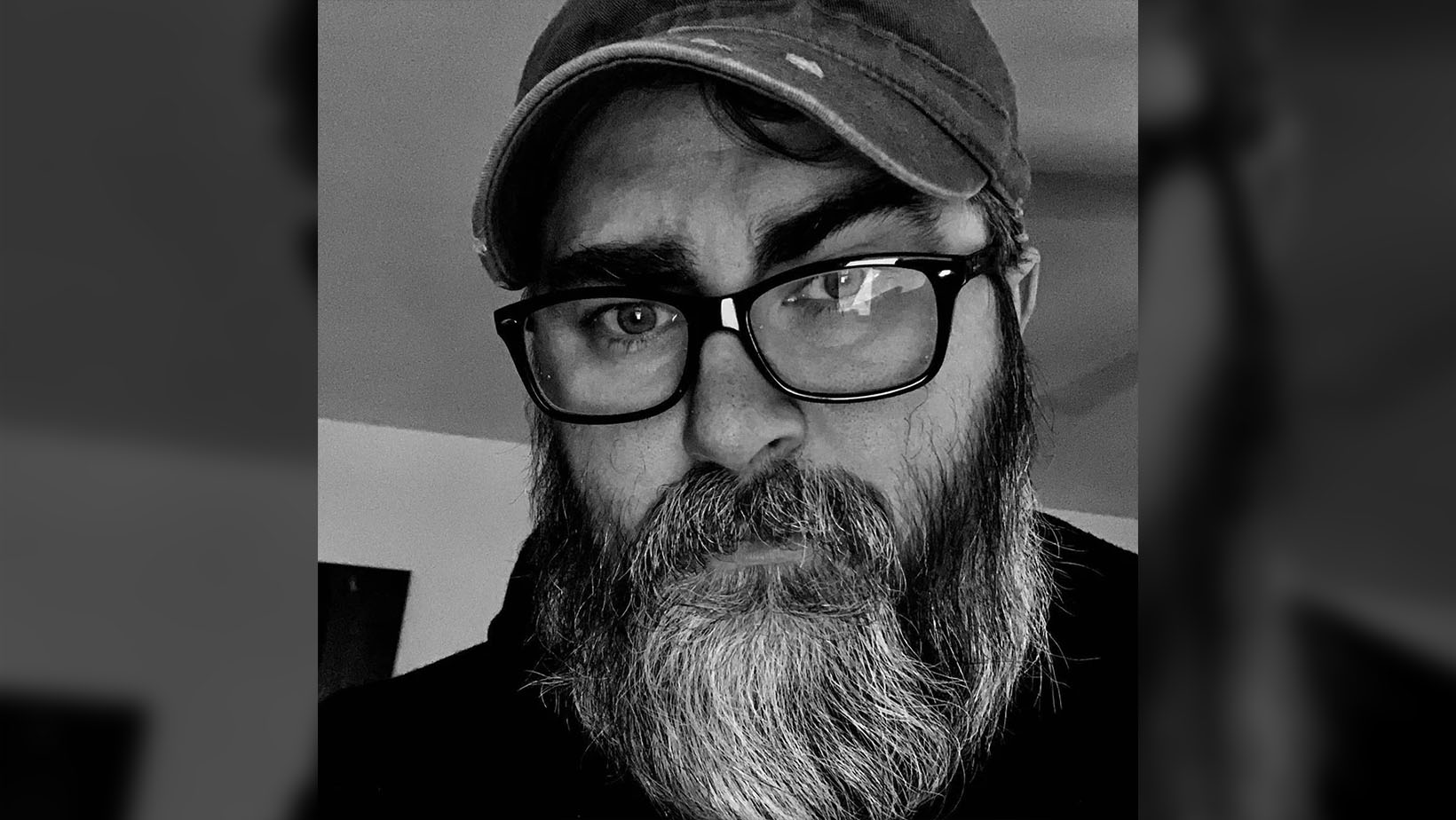

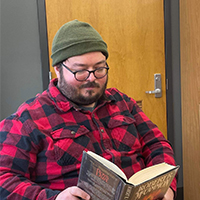

Todd Keisling was born and raised in a small town in rural Kentucky; those of you who’ve read Devil’s Creek were treated to a dark mirror image of the town in which Keisling first started to realize his true artistic power. Cutting his teeth on the fiction of R. L. Stine and John Bellairs, Todd would go on to graduate from the University of Kentucky in 2005. He now lives with his wife Erica Keisling, in a state that is not Kentucky.

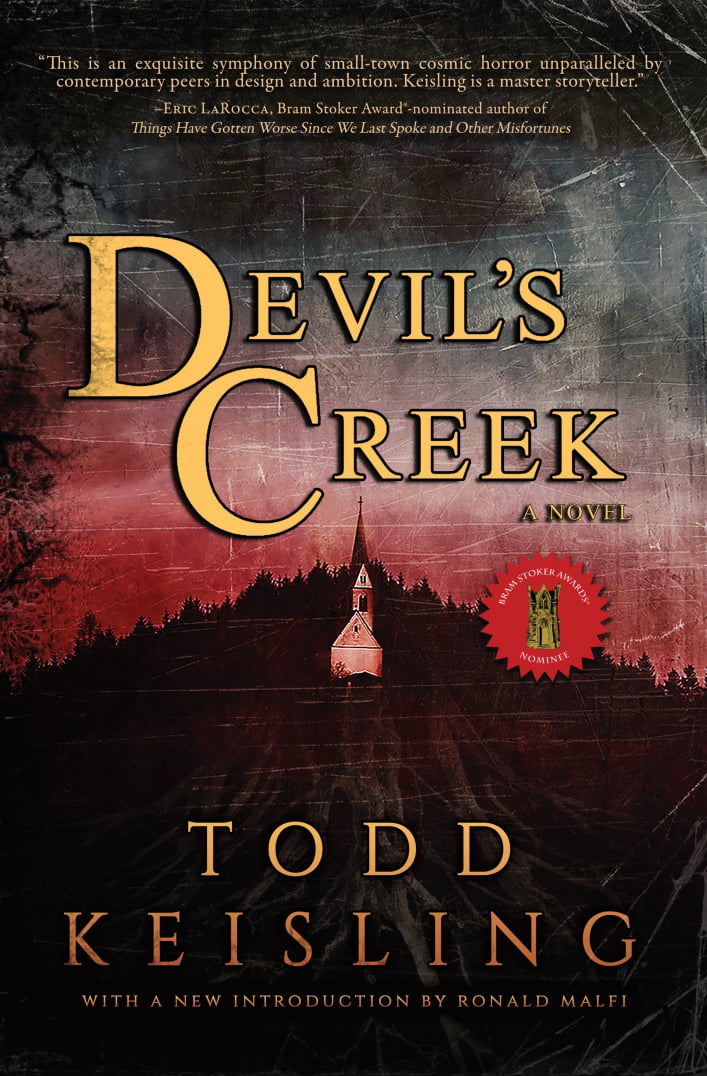

The author of The Monochrome Trilogy and Scanlines, among other books, Todd drew my attention with his novel Devil’s Creek. A work of cosmic horror dealing with the traumatic lingering cobwebs of a sinister demonic cult, Devil’s Creek is a first-rate work that has had a tumultuous publication history. First released by Silver Shamrock Publishing, the book went out of print when the publisher, over the course of a few days, closed its doors for good. Cemetery Dance Publications would go on to release a hardcover and paperback, both of which feature a revamped interior design by Keisling himself. This new paperback edition is the one I picked up with some birthday money, and from the first page, I was hooked by the hypnotic power of the prose.

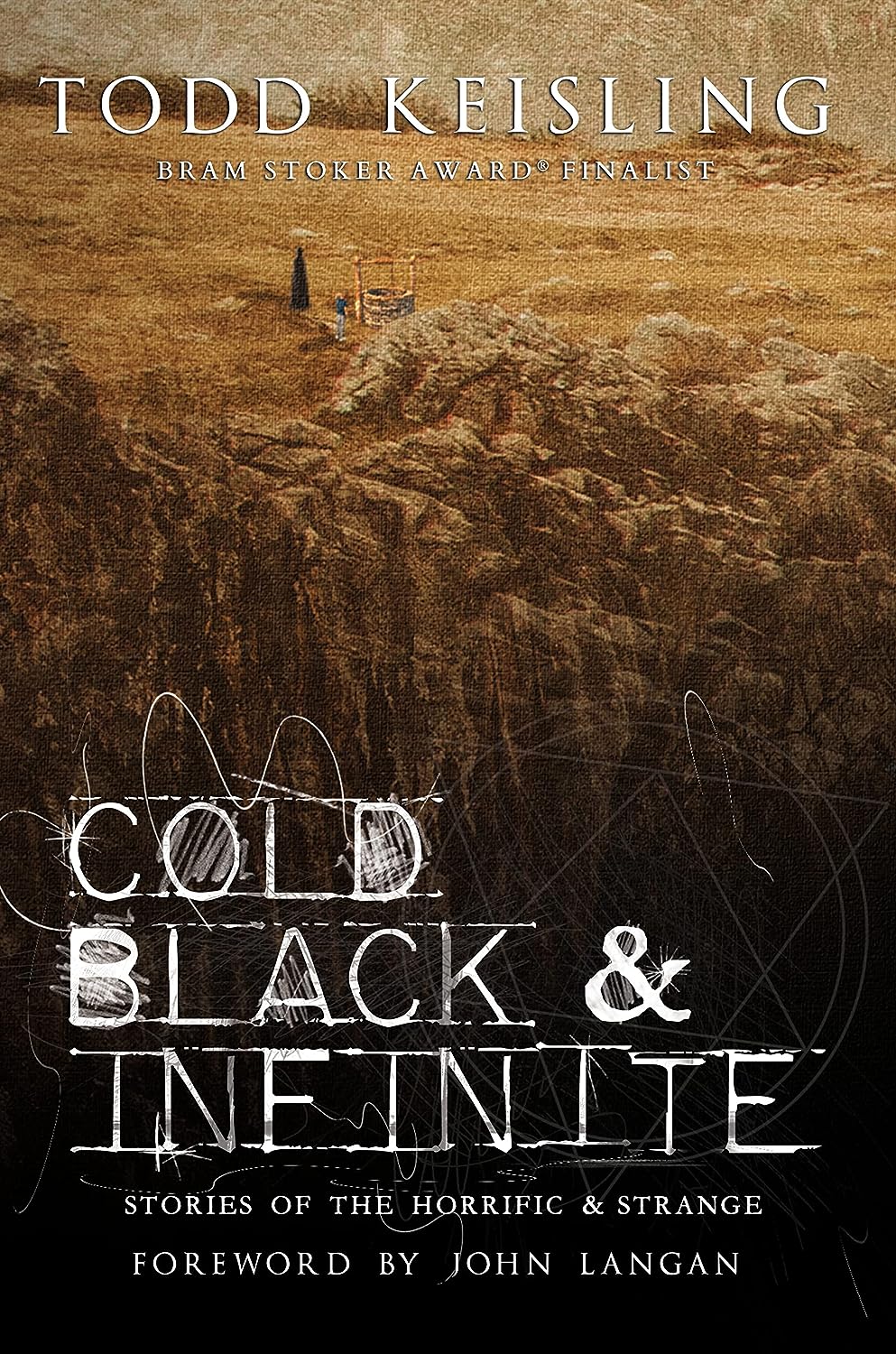

Besides the above-mentioned novels, Todd has also released a new collection of short stories in 2023―Cold, Black & Infinite: Stories of the Horrific and the Strange. Some of the work found in this new work has ties to Devil’s Creek, and rumor has it that Todd is drafting a follow-up novel. Having read my first of Todd’s books already, I know that I cannot wait to grab his new novel when it finally hits the shelves. I also know that I’ve been wanting very much to interview the man who has written one of my favorite reads of the year. Which is why I reached out and emailed him asking for this chat over email. Todd was gracious enough to say yes.

Without further ado, here is my conversation with Todd Keisling.

Thanks so much for talking with me Todd.

Sure thing, man. I’m happy to. Thanks for the opportunity.

I want to first talk about your novel Devil’s Creek, a Bram Stoker nominee. From what I understand this book was born out of an initial kernel of lore that existed near your hometown. Would you care to delve deeper into that for me?

There’s a road just off the Cumberland Falls Highway outside of Corbin, KY called Devil’s Creek Road, and it leads to the titular place. I grew up hearing about it for a couple of reasons: First, because there was a church out there once upon a time, and it burned down under dubious circumstances. Second, in high school, because that’s where the cool kids would go to hang out and party.

I guess I was around 16 or 17 when I started asking about it, because I remember my mom threatening to take away my car keys if she ever found out I went there. When I pressed her for more information, she simply said, “There’s nothing out there.”

“Then what’s the danger?”

“I mean there’s nothing out there. It’s a void.”

Naturally, that fueled my speculation. There were different tales of the church out there in the woods: Some say it was an accidental fire, or arson, or a Satanic ritual gone wrong. One way or another, the church burned, and all that remains is a foundation and a small cemetery nearby. People I knew in school told stories of their older brothers and sisters going out there to party and seeing shadowy figures in the trees. Supposedly, if you followed the roundabout around the foundation at midnight, your engine would stall, and you’d see figures in the tree line.

What intrigued me most, though, is that the old church site is miles from anything. It’s literally a spot in the middle of a national forest. Like my mom said, it’s a void.

Stauford, Kentucky is a fictional town, largely based on the town in which you grew up. Being an artsy kid and horror nerd who dealt with small-town and religious confusion myself, I can almost imagine what you felt in your youth. Did your early years shape your current artistic lens at all? Did writing Devil’s Creek feel like a way of grappling with that period in your life?

Definitely. It’s funny, though, because when I started piecing together what became the plot, I didn’t expect to be mining my past traumas and personal history all that much. All of that came about in the writing, when all those characters began showing me who they are, and I didn’t fully realize how much of myself was in the book until after the first draft was finished.

I come from a mostly conservative and religious family, but my mind just wasn’t wired to think in those terms. These days, I know I have ADHD and have a touch of autism, so it’s easy to look back and think, “Oh, no wonder I was like that. It all makes sense now.” But back then? I was just a weirdo goth kid who didn’t fit in at school or at home. I was the kid drawing in the margins of his notebook, the nerd who loved video games, who liked weird music and wore black clothing. Tall, scrawny, not coordinated enough for athletics, just a goofy-looking kid all around. Yeah. I spent a lot of time alone in my head.

Being in a religious family meant having religious expectations, though. Everyone went to church, but I never really fit in there, either. I certainly tried to, but like with school, there were unwritten rules governing who fit where. Who you were in the town, how much money you had, how nice your clothes were, that sort of thing. I lived with my mom and stepdad, and we were poor so that meant we weren’t really welcome at the bigger, more popular church in town where all the richer families congregated.

Looking back on all of those early life experiences, I guess it’s obvious that the bullying, alienation, and religious hypocrisy and fundamentalism fueled the book’s narrative.

Jacob Masters has drawn comparisons to Kurt Barlow from King’s novel Salem’s Lot. Devil’s Creek has been called your version of the same small-town horror of King’s book. In a podcast interview celebrating the rerelease of your book, you went on to say that Salem’s Lot was your favorite SK novel. It’s one of mine as well, and for the very reasons you gave in your podcast episode. Such settings as illustrated by both of these books seem perfect for creating great horror. Do you find intimate spaces to be conducive to your horror work?

It depends on the kind of story, but generally, yes. Horror (to me) is all about subversion. Let’s use Psycho’s shower scene as an example. Taking a shower is pretty intimate and vulnerable. Traditionally, a protagonist would be safe to do so. In a horror story, that’s an opportunity for suspense and tension, and in Psycho’s case, a massive subversion of audience expectation.

With respect to Devil’s Creek, I wanted to subvert the idea of my hometown as a nice and safe place to live, that it’s full of good God-fearing Christians and treats its people with dignity and respect. It isn’t, and it doesn’t, but if I say “small town America,” you probably imagine a quiet, cozy, idyllic place to live in peace.

Settings like this where there’s an underlying expectation of good are ripe for exploration with horror’s lens.

Devil’s Creek has had an interesting publishing journey, to say the least, but the re-release through Cemetery Dance has allowed you to do some dressing up for the new edition. What was it about the new publication that led you to want to make these new changes to the design?

I wanted the new edition to stand apart from the old one. Not many books get a second chance like this, so I wanted to seize the opportunity to make it something special and worthy of the Cemetery Dance catalog. This meant increasing the line spacing so it’s easier to read and adding contextual flourishes for each part of the book. The pages begin relatively clean but grow steadily more corroded and grimier as the story progresses.

Not getting into what happened with Silver Shamrock, you and many other authors were left with homeless books over literal hours. In the horror community, and especially in the indie horror community, there have been several small presses that have closed doors, mishandled funds and payments, and in general have just not done right by their authors. Ronald Kelly has gone on at length giving writers advice from his own experience in this regard; I wanted to ask you if you had any advice for new writers who may have to deal with this very issue at one time or another.

I could write an essay on this subject (and I may in the future), but off the top of my head, I think one’s diligence has to begin before they even sign their publishing contract. Look into the publisher, contact some of the authors they’ve published, and ask questions. How are they to work with? Do they pay you on time? Do they send you a royalty statement on time? How supportive are they post-release with the marketing? And be sure to ask more than one author.

When it comes to their contract (and there should always be one), don’t sign away any rights that you aren’t prepared to lose. If a publisher is looking to acquire global print rights, audio, film/TV, graphic novel rights, and anything else that is above their pay grade, ask for a revised contract without those stipulations. Chances are good that whatever they’re paying you isn’t commensurate to the worth of those ancillary rights.

And always be prepared to walk away. I know that can sting if it’s your first book and contract, but you have to be your own advocate in the indie space. Not everyone has the benefit of an agent to act on their behalf. If in doubt, always ask another author. And if that author says no or doesn’t respond, ask another one. Hell, ask me. Because we’ve all been there, and if there’s anything that pisses us off, it’s a publisher who tries to take advantage of a new author.

But if that ship has sailed and you’re already in a situation where a publisher isn’t being cooperative, then it’s time to get in touch with the other authors to pool your resources. Chances are good that if you’re being mistreated, so are they. Document everything. Go over your contract and see if you have recourse. If communication has broken down, you have other options. HWA members have access to the Grievance Committee, which can guide you and occasionally speak to the publisher on your behalf. Writer Beware is also a good outlet. Lastly, if nothing else is working, hire an attorney. It’s the nuclear option, but sometimes it’s the only way to be sure.

Your novel Devil’s Creek blew me away from the first page. If I am to understand correctly your latest collection features stories set in the same universe, and you are working on a possible follow-up novel. Would it be fair to say that you are creating your grand mythos of sorts?

Yes. It’s called the Southland Mythos. Devil’s Creek is the centerpiece. Almost all of my future works will exist in this shared universe.

You’ve managed to create a great cast of characters in your book. I felt a special kinship with Jack and Riley, as well as a deep-seated hatred for the old Reverend Jacob Masters. Which character most affected you as you were writing the story?

It would be easy for me to say either Jack or Riley, too, because they’re glimpses of me at different points in my life. But the truth is, Imogene Tremly is the character who affected me the most, because she’s based on my great-grandmother who passed away in 2005. The dream sequence at the start of part 3 is from a real recurring dream I had in college, in which Granny was always trying to protect me from that unseen evil. Writing Imogene brought Granny back to life for a while, so there was a lot of emotion behind my words whenever she came up in the story.

Would it be fair to say that religion, faith, and spirituality are topics you grapple with in your writing? Not to get too into your business, but as a man who struggles with his religious background, I found a lot to think about after reading your novel. I wanted to know if there are any nagging questions about the mysteries of the universe that haunt you in the way that Jacob Masters haunted the Stauford Six.

Yes and no. Devil’s Creek was a bit like my thesis on the horrors of religion. Personal faith and spirituality are beautiful, but they don’t translate well into a hierarchy. Once someone is assigned as its leader and set apart to dictate what that faith means for others, everything that made it beautiful is lost. Worse, it becomes toxic and poisons everything. Add a little money to the mix and now it’s the antithesis of what it claims to be. With the right amount of charisma, a leader can make their followers do anything in the name of their faith.

I was raised Southern Baptist. I’ve been to Methodist, Pentecostal, and Mormon sermons. Dabbled in new age beliefs and studied philosophy in college. I went looking for a god and never found it. These days, I don’t claim any faith, and I don’t go to church. But I also don’t claim to be an atheist. Agnosticism suits me better, I think. If there’s a higher power, we can’t conceive or even perceive it, so I choose not to worry about it.

About three quarters of the way into the novel, you delve into a serious subject (quite different from the other serious subjects in the novel), tackling the small town racial turmoil that a small town preacher tried to combat. This scene adds another layer to Jacob Masters’ character arc, and fleshes him out quite considerably. And you mentioned that the scene was based on a real world event. Would you care to share how you went about dealing with this particular issue in your book?

The scene in question relates to the expulsion of Black families from Corbin, Kentucky in 1919, after which the town became known as a “sundown town” for decades. There was a documentary made about the event (and the town) back in the early 90s called Trouble Behind, which can be found on YouTube. And there’s plenty of info about it on Wikipedia, too.

What happens in Devil’s Creek is a fictional account of that event, and it almost didn’t survive the first draft. I just didn’t feel comfortable talking about it, nor did I feel like I had any authority to do so. It’s a shameful part of Corbin’s history, and something I’ve felt ashamed of my whole life just because I was born there and lived in that shadow.

Those reasons are why several of my friends urged me to keep the scene in the book. The true story of what happened is something Corbin has never really faced, in my opinion. It’s something that isn’t talked about, like it’s been swept under the rug, and writing about it in the book was my way of bringing the atrocity to the light. And, like you said, it paints Jacob’s character (and the town of Stauford) in an entirely different light. I wanted the reader to pause and think, “Shit, maybe the town really does deserve this.”

One final question: what are you most looking forward to in the year 2024?

Not being on a book tour!

Thanks for talking with me Todd. I hope to catch you at next year’s Authorcon.

More Interviews

Ramsey Campbell Interview – A Titan of Horror Literature

A distinguished British horror author, who’s been the recipient of various awards in fiction and considered amongst the most revered veterans of the industry, Ramsey Campbell has established a strong…

Interview: Kelly Murtagh, Star and Co-Writer of Psychological Body Horror Shapeless

After premiering at Tribeca Film Festival last year, Samantha Aldana’s psychological body horror Shapeless starring Kelly Murtagh is now available on demand from Lightbulb Film Distribution. For anyone who has struggled…

Interview with Toshiaki Toyoda – The Underground King of Japanese Cult Cinema

When considering currently acclaimed Japanese filmmakers there are several names that can readily spring to mind. From the exhaustively prolific creations of Takashi Miike to the bombastic and arresting works…

Interview: Matthew Meyer “There’s Essentially a Yokai for Every Occasion”

Mathew Meyer’s is an American artist best known for his traditional Japanese style representations of Yokai, drawn with loving detail to the woodblock printing technique of ancient Japan. Mathew regularly…

James Moore is a poet and writer born and raised outside of Chesterfield, Virginia. He studied Literature and Creative Writing at Regent University, and currently lives with his wife, two dogs, three cats and a turtle in Chase City, Virginia. He loves to read classic horror novels and watch reruns of “Psych”.