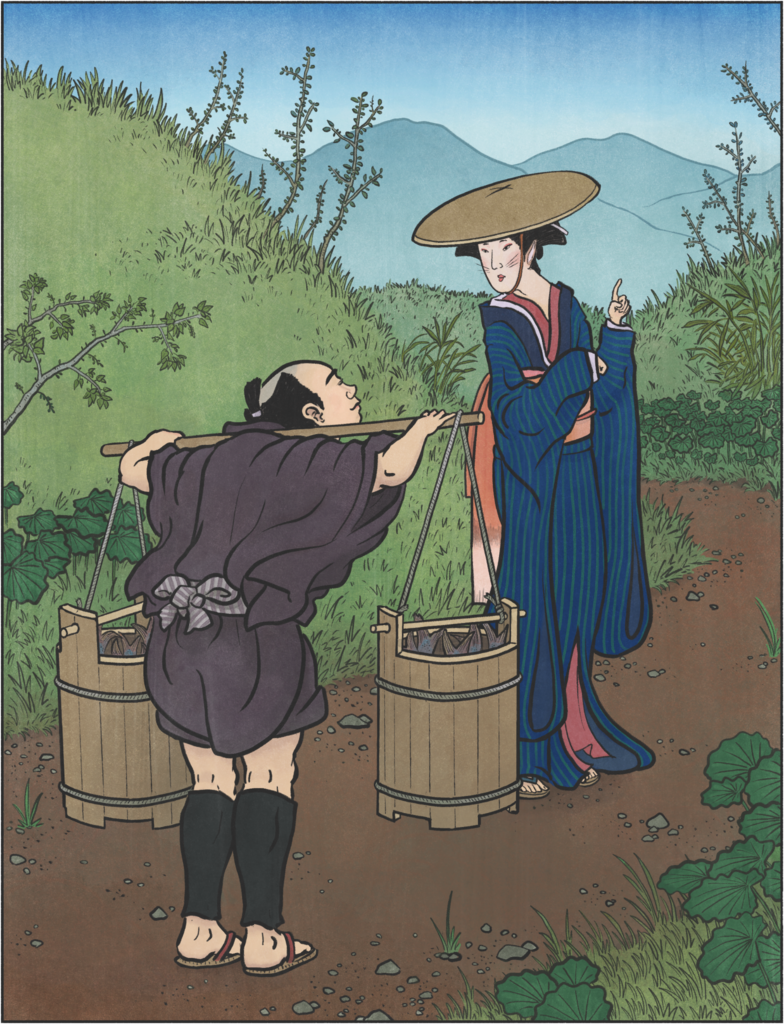

Mathew Meyer’s is an American artist best known for his traditional Japanese style representations of Yokai, drawn with loving detail to the woodblock printing technique of ancient Japan. Mathew regularly posts his work to yokai.com where he has an extensive collection of art depicting many different varieties of folklore entities. Since moving to Japan, Mathew has taken up the extensive role of researching old texts for rare, unknown folklore stories and translating them into English so they can be enjoyed by people in modern society.

I first became aware of Mathew’s art through his latest crowd funding campaign to help print and distribute the stories he has translated and his artwork for a western audience. I have viewed his extensive collection of art and have fallen for the beautiful details in each piece of work, giving each yokai a real sense of character and charm yet still retaining the time period’s style and colour schemes

Having become a big fan of his work, I decided to reach out to Mathew to try and get a better understanding of his passion for folklore and Yokai.

How old were you when you first started to draw?

I’ve always loved drawing. I was one of those kids who you could sit down in front of a stack of paper and I would just go through page by page drawing all day long. I think I probably spent most of my childhood doodling on remes of printer paper while the other kids were outside making friends, playing sports, and getting sun. Even today, when I start drawing I tend to enter a trance and forget about everything else.

Who are your inspirations for your art style?

There are so many sources of inspiration for me that it’s hard to narrow down. It’s one of those things where you see a beautiful mountain or a fantastic color in the sea, and all you want to do is capture it on paper. The same goes for artists. There are so many people whose art just fills me with a desire to create on my own. Some of them are famous, like the masters of illustration I studied in classes. Others are not, like some of the accounts I follow on social media. I tend to think of inspiration coming from specific images rather than specific artists. However, if I had to narrow it down to just two people whose work consistently moves me, I would point to James Gurney and Kawase Hasui.

James Gurney is one of the artists who made me really want to focus on art as a career, rather than a hobby or something to do just for fun. He is a master not just of color and light, but of fantasy. When he paints something fantastic, it looks so natural that it’s hard to believe that he wasn’t really there, observing it from life.

Kawase Hasui’s work is some of the most beautiful woodblock printing I have ever seen. I’m a huge fan of Japanese woodblock prints going back hundreds of years, but to me Kawase Hasui’s prints are the highest point in that genre. Like James Gurney, it’s his mastery of color and light that makes his prints stand out so far above all others.

What started your interest in Yokai?

Ghosts and monsters have always been a fascination to me, ever since I was a child. When I moved to Japan I wanted to know more about local spirits and spooks, so I spent some time looking into that subject. However, what really attracted me to them was the artwork. Yokai are a huge part of Japan’s art history, and they have such a unique and impactful appearance that it’s hard not to become enchanted by them immediately.

How long have you been living in Japan?

I moved here in 2007.

How long does it take to translate a story from Kanji to English?

That depends on a lot of things. Some of the materials I work from are very old and written in archaic scripts and speech styles which take more time to decipher. It’s always nice when I can find a modern Japanese translation of an older Japanese text. If a source has lots of historical or cultural references in it, it can take a lot more time to come up with a good English version. It’s not enough to just simply translate the text; you have to make sure context and idioms are accounted for. And English and Japanese are completely unrelated to each other, and do not have a shared literary history like is the case with European languages. That makes them especially difficult to translate between.

To give you some idea of how long it takes, I try to produce about one yokai per week, which includes both translation and painting the image. Sometimes it takes more than a week, sometimes it takes less. Each entry is different, so that’s about as precise as I can get.

What would you say are the greatest difficulties whilst translating? Do you have any advice for someone interested in a career in translation?

I think it’s easy to underestimate just how much work and education a good translation requires. It’s so much more than just swapping words and grammar from one language to another. Depending on what you’re translating, you have to understand the history and cultural context of whatever the topic is. I don’t know how qualified I am to offer advice, because while I do translate things, I don’t really consider myself as having a career in translation. But I can say that one of the things which has been so helpful to me has been living in the language that I work in. While it wouldn’t be impossible to do my work in my birth country, living in Japan has made it so much easier to work in the language. I would recommend that anyone interested in a career like that spend as much time living abroad as possible.

What would you say are your three favourite Yokai and your reasons why?

My favorite yokai would have to be ao andon. It represents the very essence of fear itself. So much of what we fear is not real, but just a construct we make in our minds. Ao andon is the physical manifestation of that idea.

After ao andon, it’s impossible for me to pick a second and third. Every yokai has something wondrous about it that attracts me to them, and my favorite ones change daily depending on my mood. But I do like that there’s essentially a yokai for every occasion.

What has been your favourite part of making your newest book The Fox’s Wedding?

My favorite part of all of my yokai projects is interacting with yokai fans. I started working with yokai because there was not a lot of information about them in English, and very few people knew about them. It’s a very niche subject. But niche subjects tend to attract passionate people. While there certainly are casual yokai fans, I think that yokai tend to inspire a lot of devotion and passion. And people who are passionate about something are always fun to talk to!

Do you have any other projects you would like to mention?

I have a Patreon (patreon.com/osarusan) which supports me throughout the year and helps me keep on creating yokai. Patrons can get monthly yokai postcards, as well as discuss behind-the-scenes information about my illustrations and translations that end up not going into my books or on yokai.com. And since I get so many emails from yokai.com readers who have requests for what yokai I paint next, I’ve had to limit requests to just my patrons as well. I think it’s a wonderful community of very passionate yokai fans. For anyone who has special yokai requests or wants to get even more background on the yokai I post, I would recommend joining my Patreon!

Grimoire of Horror would like to thank Mathew for taking the time to speak to us

More Interviews:

Interview with Alex DiVincenzo and James Cilano of Witter Entertainment [Video Content]

Check out our newest interview with James Cilano and Alex DiVincenzo, the masterminds behind Witter Entertainment and Broke Horror Fan. They have been hard at work releasing beloved classics as…

Interview with Felix Blackwell, Best Selling Author of Stolen Tongues

Every indie creator hopes to make it big some day, but with limited marketing budgets and the lack of a big publisher/production company backing their projects, success is often a…

An Interview with The Vamps – Pinky Violence Royalty Reiko Ike and Miki Sugimoto Talk Sex

Back in the 1970s, the names of Reiko Ike and Miki Sugimoto were on everyone’s lips. Hailed as the “queens of porno”, they not only became exploitation cinema royalty but…

Interview with Filmmaker Chad Ferrin – Writer & Director of the upcoming film ‘Pig Killer’

No stranger to the horror genre, Chad Ferrin found his footing in the film industry as a production assistant on such films as Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers and…

Hey there, I’m Jim and I’m located in London, UK. I am a Writer and Managing Director here at Grimoire of Horror. A lifelong love of horror and writing has led me down this rabbit hole, allowing me to meet many amazing people and experience some truly original artwork. I specialise in world cinema, manga/graphic novels, and video games but will sometime traverse into the unknown in search of adventure.

![Interview with Alex DiVincenzo and James Cilano of Witter Entertainment [Video Content]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Interview-Witter-Entertainment-365x180.jpg)