In a career that spanned four decades, prolific novelist Shinji Fujiwara explored a wide range of genres in his work, though is most famed for his 1950s suspense stories. The widespread popularity of his work quickly lent itself to the medium of film, and he would eventually be dubbed “film’s favourite novelist” due to the sheer amount of his stories that were adapted (57 between 1951 and 1991 to be exact). The late 60s proved one of the most in-demand periods for his adaptations, and films such as A Colt is My Passport, A Certain Killer, and Blackmail is My Life heralded a new era of gritty Japanese neo-noir. This era focused heavily on male-dominated hard-boiled stories, but in 1969 this trend was bucked with Art of Assassination (or Female Killer: Bitch to give its direct translation) – an adaptation of Fujiwara’s story The Killed Man.

At first glance, Kayo (Kyoko Enami) is your average café hostess – mild-mannered and seemingly even a little shy – in reality, this is merely a cover for her true occupation as an assassin-for-hire. The film opens with a demonstration of Kayo’s skill: walking along a hallway towards her unaware target, she passes him whilst simultaneously leaning back and executing him without ever missing a step. Her weapon of choice is an inconspicuous ring that hides within it a spring-loaded telescopic 4-inch needle, which she skilfully stabs into the back of the neck of her target, resulting in a quick and silent kill.

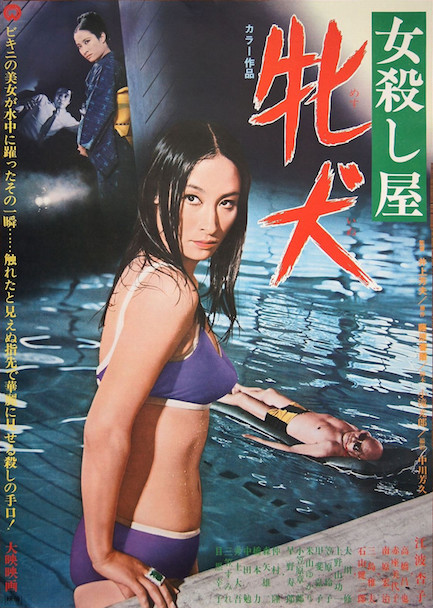

When the corrupt politician Tobita (Masao Mishima) fears that finance kingpin Ishizuka (Kenjiro Ishiyama) is growing too powerful and influential, he tasks his associate, a business owner called Abe (Masaya Takahashi), to deal with him via any means necessary before he becomes a true threat. After consulting with his shady underlings, a plan is put together to assassinate Ishizuka with the job eventually going to Kayo. Kayo immediately takes on the hit, with the prospect of the large payment upon completion fuelling her interest. After staking out her target, her mission will be no easy task as Ishizuka is constantly accompanied by a large entourage of bodyguards. Kayo finds that he is at his most vulnerable when visiting a mountain resort, where he is often found lying in the pool; although sniping him from a distance will be no option as he is surrounded at all times by his goons. Kayo decides on a much riskier plan, swimming underwater directly under their noses and stabbing Ishizuka in the neck through his floating lilo.

With the ensuing panic in the pool, Kayo makes her escape without drawing attention and manages to drive away seemingly undetected. However, it seems the mission might not have been as successful as she first thought, as she notices a car following her at speed. Driving down the mountain, she quickly discovers that her brakes have been cut and narrowly avoids plunging to her doom. It is revealed that Abe’s team got greedy and, underestimating Kayo, thought that they would be able to kill her after she had completed her mission and avoid paying her. The usually ice-cold Kayo has always kept her killing purely professional, however, now that she herself has been targeted, for the first time in her career she burns with true anger and will stop at nothing until she has taken her revenge on everyone responsible for putting the hit out on Ishizuka.

There is no denying the similarities between Art of Assassination and Daiei’s earlier Fujiwara adaptation A Certain Killer. Both films follow a stoic and highly professional assassin, who is ultimately betrayed by their client who tries to kill them to avoid paying for their services. Despite this likeness, Art of Assassination is far more than a mere gender-swapped version of the prior film, and holds its own distinct identity, thanks in large to Kyoko Enami’s Kayo.

Already the star of Daiei’s long-running Female Gambler series, Kyoko Enami was very much the studio’s signature femme fatale, and, as such, was an obvious choice for the role of Kayo. Much like A Certain Killer’s protagonist, Kayo is a person of few words, who is meticulously dedicated to her work. However, in Kayo’s case, it is clear that this life is more than just a job, and the emotionless façade of a killer cuts all the way to her soul; any appearance of her as a normal woman seems to be merely an act. When she is stalking her victims, Kayo quite literally resembles a black widow with black high heels, stockings, and a shiny black leather trench coat; all topped off with a large pair of dark sunglasses. In this form, she is dedicated 100% to the kill with an almost mindless tenacity, not at all dissimilar to a Terminator. When she is dressed down, Kayo has a thin line of eyeliner applied to her lower eyelids which exaggerates Kyoko Enami’s naturally vulpine eyes, subtly enhancing her predatory gaze.

Art of Assassination stands out among other female assassin films because of its lack of sexuality. As an extension of her bitter and cold-hearted nature, Kayo is completely asexual with a clear disdain for humanity. On the handful of occasions where she is treated with kindness by the young female patrons of her café, she appears visibly uncomfortable and disturbed, though it is not clear whether this is out of annoyance or a deeper emotional reaction. Kayo’s past is firmly kept as a mystery with the exception of a single flashback featuring a photo of her as a child, kneeling in a pool of blood.

Neither Kayo nor the film exploits her gender and is refreshingly free of the overdone trope of a highly sexualised seductress assassin. The only hint of femininity at all comes purely from the poster, which seems desperate to imply some form of eroticism by showing Kayo in the pool. The only way that Kayo ever takes advantage of her gender is via the general inconspicuousness of women in a male-dominated society. As a woman, she has the natural power to go unnoticed, and even in a room filled with bodyguards, no man would give her a second glance.

Having worked together on four Female Gambler films previously, Yoshio Inoue is clearly a master of directing Enami. The world of the film is very much treated as her playground as she comfortably navigates it like a lion prowling its killing ground. Despite her eye-catching appearance in an all-black outfit, Kayo naturally blends into the background, confidently slinking behind the backs of her prey. Enami expertly portrays her emotional brick wall of a character, somehow giving brief glimpses of personality buried deep in the animalistic and uncaring exterior. These cracks are vital in making Kayo feel like a real person rather than an unstoppable killing machine.

Inoue’s understated direction intentionally reflects the cool and collected character of Kayo. Her killings are filmed with a matter-of-fact calmness, which only highlights their brutality; there is no need for frenetic camerawork to provide a false sense of action. The camera instead sits at a comfortable distance and lets Kayo take care of business as the audience follows her deliberate and confident actions. This approach also serves the mysterious character of Kayo, keeping her at a distance from the audience so we are watching her killings voyeuristically rather than accompanying her on her journey.

As a precursor to the popular female assassin subgenre, Art of Assassination stands out among both contemporary and later films with its unique protagonist and avoidance of stereotypical seductress tropes. The incomparably cold Kayo is both a captivating enigma as well as a genuinely unnerving character in her unflinching commitment to murder. In her signature black outfit and deathly stare, there is no doubt that Kayo was an inspiration for Female Prisoner Scorpion’s iconic Sasori, as well as an archetype for a wide range of female assassins going forward. At times, Art of Assassination can become a little repetitive with Kayo’s killing methods rarely deviating from the usual pattern, although in general the enthralling Kayo rarely allows the audience’s attention to drift to anything but herself.

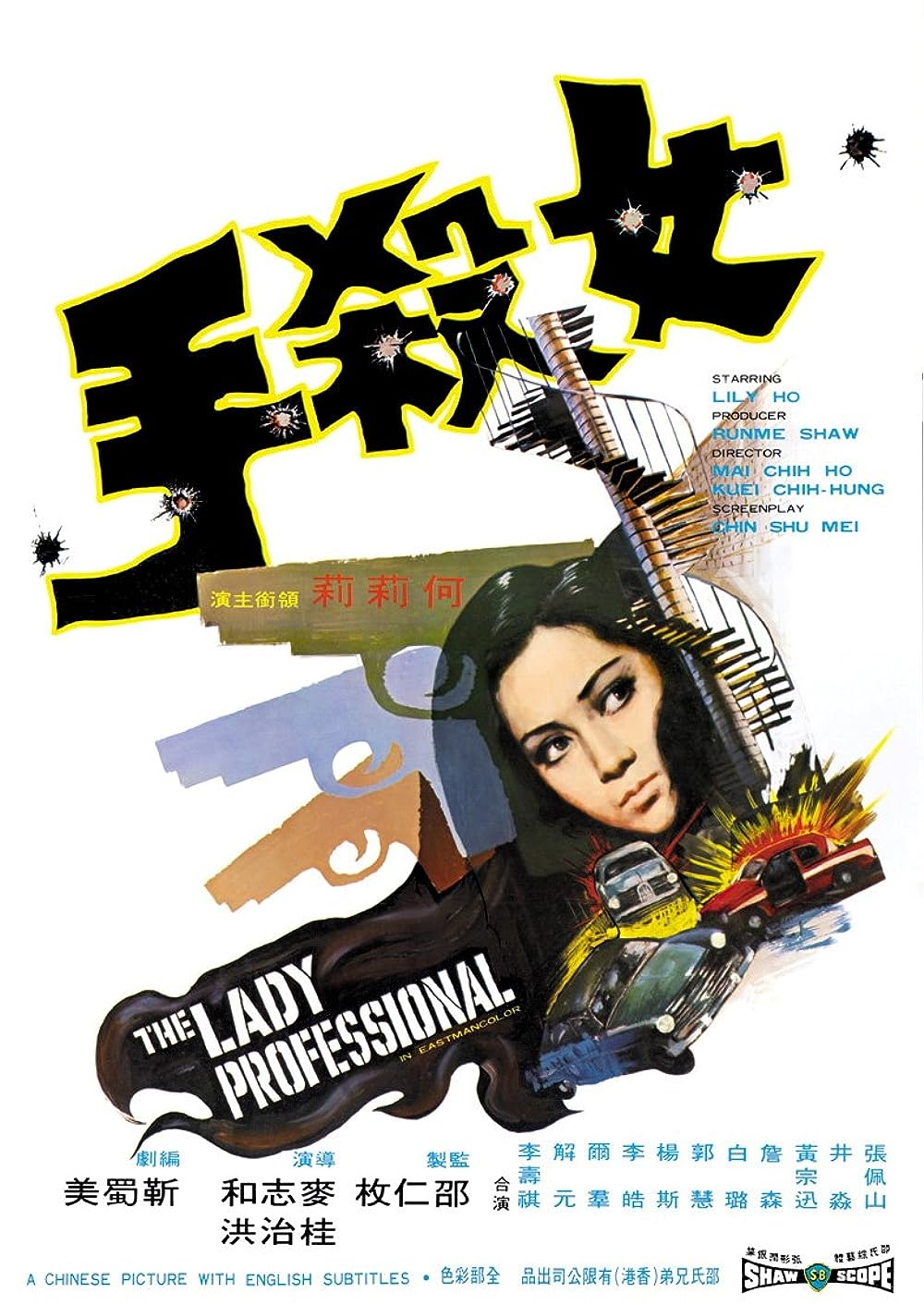

In 1971 Art of Assassination would receive a Hong Kong remake courtesy of the Shaw Brothers, retitled as The Lady Professional with Lily Ho in the lead role – now named Ge Tianli. Despite being made in Hong Kong, The Lady Professional is undeniably a Japanese affair thanks to its co-director Akinori Matsuo (credited as Mai Chih Ho). Visually it is largely indistinguishable from the Japanese original, with key scenes practically recreated shot for shot. Nevertheless, The Lady Professional is far from being a one-to-one remake of the Art of Assassination and ultimately takes its own unique direction with the increased levels of action expected of a Shaw Brothers film.

The difference in tone is telegraphed straight from the opening: Unlike Art of a Assassination with its understated example of Kayo’s killing talents, The Lady Professional goes for the opposite approach. Instead of encountering her target in a deserted corridor, Ge Tianli is at a busy theme park. Taking a less personal touch she kills her target not with a ring but with a makeup compact which fires a steel dart from a distance. When the crowd notices that she has killed a man, a chase ensues, all accompanied by the plagiarised theme tune from From Russia With Love.

Ge Tianli is given a completely original and fleshed-out backstory which changes the dynamics of the entire film. After her family is attacked and murdered by a gang of loan sharks, she stops at nothing to get her revenge on them. When she is spotted and photographed killing one of them at the theme park, she is then blackmailed into becoming a professional assassin.

Kyoko Enami, with her exceptional portrayal of Kayo, left almost impossibly large shoes to fill; fortunately, with her new backstory, the character of Ge Tianli is different enough for Lily Ho to make her own. With the protagonist transformed from an ice-cold professional killer, to a desperate woman forced to kill, Lily Ho is able to bring more emotion and charisma to the role. As a result, Ge Tianli is much more likable than Kayo, and a character that the audience can really get behind.

Even though the two films are so similar, their differences make it difficult to say whether one is superior to the other. Whilst Art of Assassination is a slower neo-noir brooding with nihilism, The Lady Professional is more a straight-up action movie. Despite hitting many of the same plot points, the overall story of the two films is twisted to fit the different tonal interpretations, leaving both feeling unique and fresh. Helped along by uniquely different protagonists, both played to perfection by their respective actresses, The Lady Professional feels more like a complementary counterpart of Art of Assassination rather than a direct remake. It is hard to recommend one film over the other, though The Lady Professional is arguably the more accessible of the two, having received English subtitled VCD and DVD releases.

More Film Reviews

Homunculus (2021) Team Review – What Would Your Trauma Look Like?

Susumu Nokoshi once worked for a top foreign financial company. He is now a 34-year-old homeless man, usually found around a park in Shinjuku. He then meets medical school student…

The Empty Man (2020) Team Review – Fear The Abyss

“The Empty Man is a supernatural horror film based on a popular series of Boom! Studios graphic novels. After a group of teens from a small Midwestern town begin to…

Reborn (2018) Film Review: A Frustrating Miss

A young actress gives birth to a stillborn baby girl, but an accident in the morgue brings the baby back to life… with electrokinetic powers. The child is abducted by…

The Sandman Series 1 Review (2022) – A Neil-Perfect Season

Let’s jump straight to the point for once: Netflix has largely succeeded in adapting Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman, a popular and critically-acclaimed graphic novel which had been deemed “unfilmable”. With…

Till Death (2021) Film Review – Separation Can be a Nightmare

Till Death is the adaptation of a screenplay written by Jason Carvey and is also the directorial debut for S.K. Dale. Megan Fox plays the role of Emma, a young…

Cobweb (2023) Film Review – What lurks in the Bedroom Corner

Coming in at under 90 minutes, Cobweb (2023) is a relatively star-studded little gem, perfectly suited for an entertaining bit of Halloween indulgence. Directed by Sam Bodin (who has Netflix…

Homunculus (2021) Team Review – What Would Your Trauma Look Like?

Susumu Nokoshi once worked for a top foreign financial company. He is now a 34-year-old homeless man, usually found around a park in Shinjuku. He then meets medical school student…

The Empty Man (2020) Team Review – Fear The Abyss

“The Empty Man is a supernatural horror film based on a popular series of Boom! Studios graphic novels. After a group of teens from a small Midwestern town begin to…

Reborn (2018) Film Review: A Frustrating Miss

A young actress gives birth to a stillborn baby girl, but an accident in the morgue brings the baby back to life… with electrokinetic powers. The child is abducted by…

The Sandman Series 1 Review (2022) – A Neil-Perfect Season

Let’s jump straight to the point for once: Netflix has largely succeeded in adapting Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman, a popular and critically-acclaimed graphic novel which had been deemed “unfilmable”. With…

Till Death (2021) Film Review – Separation Can be a Nightmare

Till Death is the adaptation of a screenplay written by Jason Carvey and is also the directorial debut for S.K. Dale. Megan Fox plays the role of Emma, a young…

Cobweb (2023) Film Review – What lurks in the Bedroom Corner

Coming in at under 90 minutes, Cobweb (2023) is a relatively star-studded little gem, perfectly suited for an entertaining bit of Halloween indulgence. Directed by Sam Bodin (who has Netflix…

Hi, I have a borderline obsession with Japanese showa-era culture with much of my free time spent either consuming or researching said culture. Apparently I’m now writing about it as well to share all the useless knowledge I have acquired after countless hours surfing the web and peeling through books and magazines.