Imagine yourself 12 years ago. You are an anime and manga fan who now has even more access to your favorite shows than ever before thanks to internet massification. Things seem to be looking up, but suddenly you get bombarded by a virtual headline like this “JAPAN IS BANNING MANGA TO PROTECT CHILDREN”. At first, you laugh it off. It is impossible that Japan is cutting off one of its more rentable commodities like manga. Yes, manga can be controversial but still, canceling a whole type of media sounds harsh. You click the link to know more and fear sets in a bit more as fancy legal buzzwords and phrases like “law passing”, “harmful publications”, “non-existent youth” and “Bill 156” portray the legal tone and seriousness of the matter. Are manga creation and distributors in real danger? Western news outlets seem to make it appear as such.

What I am describing here is not a product of imagination. It happened in 2010, when the Tokyo Metropolitan Ordinance on Health Development of Youth Revision-AKA Bill 156- caused a heated debate about freedom of expression and censorship. While in Japan there was certainly a discussion that ensued protests from both sides, on our shores the whole controversy took a fear-mongering approach that obscured a real understanding of how Bill 156 came to be and what it really what was about.

What is the Tokyo Metropolitan Ordinance on Health Development of Youth anyway? Why did it target manga?

One of the first misconceptions about the Tokyo Metropolitan Ordinance on Health Development of Youth (TMOHDY for short) is that this was a brand-new law passed in 2010. In actuality, this ordinance was enacted in 1964 with the purpose to promote the improvement of the environment for adolescents. This means that it focused mainly on creating restrictions to regulate media, toys, cutlery, and indecent behavior that may hinder the proper development of the youth. In terms of “harmful publications”, this ordinance focuses on documents, movies, or books that may “stimulate sexual feelings”, “promote cruelty”, “significantly induce suicide or crime” or express sexual acts that violate social norms in an unreasonably exaggerated manner. Publications that fall under these criteria cannot be sold, distributed, or loaned to young people and, when sold in stores, they should be separated and labeled as adult material. If publishers or sellers do not comply, they will be punished with a fine.

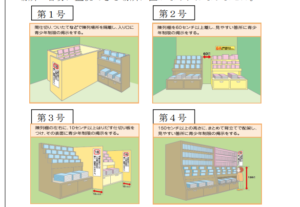

Layout for restricted manga that includes works falling into Bill 156’s criteria

How are said publications selected? It seems that a government-designated council purchases between 120-140 books displayed on general bookshelves and convenience stores and they review them. Later, this council shares their results with the Healthy Youth Development Council, and they decide which titles need regulation. After designation, this information is shared through a governmental website, and postcards are sent to convenience stores with the resolution. This bill only covers the Tokyo area but it does influence the actions of publishers in other prefectures.

Thus, regulation of manga is not something new or groundbreaking as news outlets made it look in 2010. As in many countries around the world, the Tokyo government regulates questionable media that is readily available in places accessible to children. No manga has or will disappear in the middle of the night to never be published again. That being said, why did this ordinance become a hot topic 12 years ago? Laws are constantly changing, and the 2010 revision was controversial due to the ambiguity and ulterior motives of the politicians promoting it.

Enter Bill 156, the revision that freaked the hell out of everyone

There has always been this idea that Japan is some sort of no man’s land when it comes to child porn. While it is fair to say that their laws regarding this problem are lax when compared to other countries, this misconception is inaccurate since laws about the matter do exist, and some are similar to other nations. However, two legitimate points of controversy about this topic are simple possession of CP and fictional depiction of children in adult content. The former was finally regulated in 2014 after a lot of international pressure, but the later still is a sore spot that remains unresolved to this day.

For years, international agencies like UNICEF have been lobbying Japanese policymakers to increase restrictions concerning how children are depicted in manga, anime, and video games. Many fans, both Japanese and overseas, have issues with the way some media sexualizes children, so this initiative presents some positive points. Despite the annoying habit of certain groups to portray Japanese people as depraved and unmoved to lolicon and shotacon, believe it or not, both genres are just as polemic in Japan as any part of the world.

To clarify, TMOHDY‘s revision in 2010 was not controversial for wanting to control media depicting minors in sexual situations. Manga authors and freedom of expression promoters were worried about the law’s ambiguous terminology and who would get to decide what exactly an “anti-social” sexual situation depicted in fiction involving children was that needed to be regulated so harshly. Ken Akamatsu, the author of the famous harem-manga Love Hina was one of the main opponents of this revision. While many Western forums portrayed him like someone who only wanted a free-range to draw ecchi manga, intervention was way more nuanced. As he discussed in a Twitter thread: “There is no victorious group regarding the TMOHDY. Everyone loses in some way and hate each other. I wish there was a place in the net where to negotiate while giving some profit to the other party”.

He later mentioned that he is not against regulations, by expressing that he would gladly avoid drawing something that it is regulated. In fact, his plea lays in the fact who are making these rules and what they are real intentions behind them. These fears were not unfounded. One of the biggest promoters of this law was Shintaro Ishihara, a politician who made extremely homophobic statements while promoting this revision, such as, “[The bill 156] is not just about the kids. We have got homosexuals casually appearing even on television. Japan has become far too untamed.” Also, right-wing political parties and conservative associations were the ones supporting this change, so it was normal to think that, once passed, the definition of “harmful” would be influenced by their own beliefs.

Manga parody making fun of Shintaro Ishihara

Let’s put it this way. Almost everyone in their right mind would agree that works like Boku no Pico, Kodomo no Jikan, or My Wife is an Elementary School Student should be kept as far away as possible from bookstores and convenience stores where children can find them. But, what about titles like A Cruel God Reigns, Bloom into You, and Umibe no Onnanoko? These are stories that involve minors. Granted, some of them are way less explicit than Boku no Pico, but they do explore sexual themes just the same. The main difference is these works are full of nuances and the sexual acts portrayed are not exploitative. Because of this, the ambiguity of the ordinance plus the evident biases of the people promoting it would not offer enough reassurance of a fair judgment. While we have stated the TMOHDY does not have the power of banning titles, the restrictions applied can hinder the distribution scope, or encourage self-censorship by publishers, and end up discontinuing certain titles even if this ordinance extends only in the Tokyo area. This situation could end up depriving children and teens to enter into contact with manga that can validate homosexuality in a positive manner, for example.

So, what happened to Bill 156?

After a series of mishaps, like a polemic TV interview with an Ishihara subordinate showing the manga My Wife is an Elementary School Student full of censoring post-its (which this manga definitely needs but not in the specific pages shown), and vocal opposition of manga artists, this specific version of the bill was scrapped. Unfortunately, Ishihara stated that while the bill may have been badly worded, the intent behind it was good and only needed to be redrafted.

Scene from the infamous interview

In November 2011, a new revision was submitted and approved. This time, it removed the term “non-existent youth” completely and focused on “non-existent crimes”. This means that works depicting sexual intercourse or sexual intercourse-like acts that touch punishment laws or incest with unreasonable praise and exaggeration are the ones penalized. Since My Wife is an Elementary School Student portrays an illegal marriage and lewd acts involving minors, it still fell into the bill criterion. Aki Sora was also restricted due to its portrayal of incest. The first and third volumes were discontinued since they were the most objectionable ones. However, it was not because of the bill forbidding its distribution. The publisher simply wanted to avoid conflict.

Bill 156 Now, Ken Akamatsu, and Final Thoughts

You might be wondering now if Bill 156 had any impact at all. The answer is both yes and no. Again, this bill never had the power to ban manga, anime, or video games outright. At best, it made them less accessible and unable to be listed on Amazon. You can still buy them, but you have to look for them in more specialized stores where they are placed in a more restrictive manner, as with any other adult content. Since this makes the titles less rentable, some publishers might want to think twice before investing in work at risk of being penalized, but that depends purely on their own business model.

The only concern that this bill has raised is that many of the manga being penalized in the last years are the ones involving BL (Boy’s Love). Again, it does not mean these titles are being banned but indeed put at disadvantage in terms of exposure. The reason behind choosing them is not clearly stated, other than “[Stimulating] sexual feelings and impede the healthy growth of adolescents”. The board in charge of deciding which manga needs restrictions are mainly members of ethics councils, PTAs, the Film Classification and Rating Organization (Eirin), and the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly. There is one representative of a Regional Women’s Organization Federation, a law academic, and a Human Rights specialist. Still, one might wonder if the bias that many feared in Ishihara is alive and well in this group.

Despite the pessimistic state of current affairs, efforts are being made to regulate instead stark attempts of censorship. The same Ken Akamatsu has reinvented himself as a defensor of free expression and protector of fellow manga artists. After 2010, he launched “J-Komi” (later rebranded as Manga Library Z), where out-of-print media could be distributed and give some revenue to the authors, who previously did not receive any payment for their work, even if it was being sold in second-hand stores. Later he would become chief adviser of the Group for Protecting Freedom of Expression and, in 2022 he won a seat in the House of Councillors in Japan, representing The Liberal Democratic Party. Since then, he has been very vocal about his focus on censorship in his campaign. Again, many news outlets are misrepresenting his intentions, and of course, completely forget to mention the role he played during the Bill 156 debacle. It is fun for some to create a clickbait title deeming him as an “otaku” who woke up one day and wanted to cosplay as a politician. The truth is that he has been involved in this matter for decades. Even if you still disagree with his opinion on the depiction of minors in the manga, his point of view offers a much-needed balance to rampant puritanism disguised as concern for the youth.

Ken Akamatsu during his political campaign

Wrapping things up, I am baffled at how reductive news informed TMOHDY and Bill 156 and how easily we panicked back then and we still panic today. I let myself be influenced by a telephone game of exaggeration and buzzwords, and I did not know it until many years later. Luckily, now I find solace in knowing I have all the information I need to understand this little piece of Japanese media history, and now I am sharing it with others, so misinformation is no longer a problem when it comes to the Tokyo Metropolitan Ordinance on Health Development of Youth Revision.

SOURCES

おたぽる. (2019, August 1). 不健全図書指定されまくるボーイズラブ でもホントに損害があるのか? (2019年4月3日). エキサイトニュース. https://web.archive.org/web/20191021104932/https://www.excite.co.jp/news/article/Otapol_201904_post_59443/

和泉彼方@土曜日 東エ-43a 萌え尽きて。(@kanata0954). (2010, December 16). 【16日日中分追加】都条例可決を受けて、赤松健先生のツイート. Togetter. https://togetter.com/li/79541

Anime News Network. (2010, December 13). Tokyo’s Youth Ordinance Bill Approved by Committee (Updated). https://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2010-12-13/tokyo-youth-ordinance-bill-approved-by-committee

Office for Promotion of Citizen Safety. (2021). 青少年健全育成条例の運用. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.tomin-anzen.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/jakunenshien/jyourei-unyou/index.html

H. [Hazel]. (2022, February 23). Who Was Responsible For This Anime? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zHTBvvRCqmk&feature=youtu.be

Japan: Governor Should Retract Homophobic Comments. (2020, October 28). Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2011/02/01/japan-governor-should-retract-homophobic-comments

McLelland, Mark J., Thought policing or the protection of youth? Debate in Japan over the “Non-existent youth bill”, International Journal of Comic Art, 13(1) 2011, 348-367. https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers/260

More Japanese Deep Dives

Japan Deep Dive: Iki Ningyo, The Cursed Living Doll

Welcome, fellow weirdos, to another captivating exploration of Japanese culture. Prepare yourselves for a spine-chilling journey as we delve into a tale filled with possessed dolls, ancient curses, and the…

Samurai Fart Battles – The Lighter Side of History

When we picture samurai warriors, images of honor, discipline, and fierce sword battles come to mind. However, there is a hidden and often overlooked aspect of samurai culture that was…

Denpa Visual Novels – The Big Three Denpa Games

Hi fellow weirdos! This is Javi again, researching for you to bring you another interesting bit of Japanese media. We have previously discussed the term “Denpa,” which, according to Jisho.org,…

Yu-Gi-Oh Hangman Card Urban Legend – The Cursed Game Card

In the early 2000s, anime experienced a surge in popularity among Western audiences, marking a peculiar time for anime fans. However, as this unique form of animation gained mainstream attention,…

Hi everyone! I am Javi from the distant land of Santiago, Chile. I grew up watching horror movies on VHS tapes and cable reruns thanks to my cousins. While they kinda moved on from the genre, I am here writing about it almost daily. When I am not doing that, I enjoy reading, drawing, and collecting cute plushies (you have to balance things out. Right?)