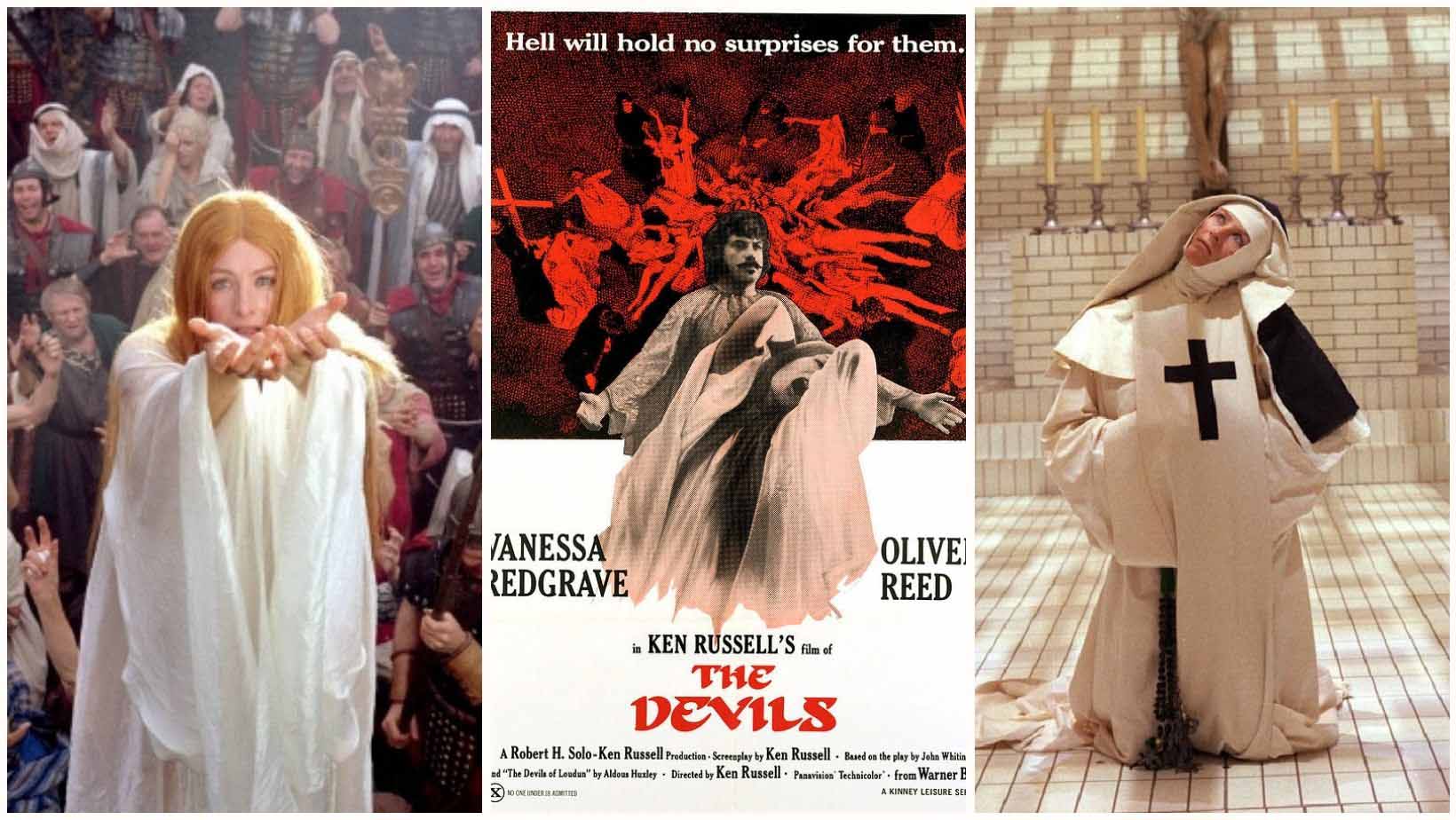

As the temperature of sin and plague begins to rise within the town of Loudun, France, it is hard not to notice the white brick walls that fortify the commune rising above it all; an unnervingly blank canvas waiting to be smeared. Like Chekov’s gun, there are expectations by the third act something must explode upon their pristine quality. Surely it won’t be hard to find something rupturing within such a famously X-Rated film. With all of the fever blisters beginning to run, bodies burning in the streets, enemas spitting back and the increasing danger of whirling dervish nun taint reaching maximum crucifix thrust, stains should surely be a coming. But the immaculate quality of these walls will somehow remain intact through much of the films messiest moments. They stare back unflinching at the desecration that pantomimes in front of them. In a film steeped in religious sermonizing about the frailty of man and the temptations of Satan, they will serve as a reference point as to how far we have fallen, and how dirty we have become in the process.

It will be upon this stage, conveniently barren of nearly everything but the clutter of sin, lust, death and deformity, that director Ken Russell will find himself delightfully well positioned to provoke his audience. Granting them as little space as possible to look away, church desecration’s and tangles of naked limbs will be presented as both scenery and much of the plot for those watching, whether or not they asked. With nothing but the theater stub in their pocket to prove any sort of consent, Russell proceeds without restraint, and those in the audience will have little choice but to watch as every grimy crevice of the human body is exposed for contemplation. And for those poor souls in the front row, maybe they can only hope to find distraction by counting the sweating pores upon each and every butt-crack pushed into frame, since clusters of pores are a much better alternative to dwell upon than other things.

At first glance, being so explicitly offensive initially seems to be a particularly counter intuitive approach for the director to take here. The Devils is, after all, primarily a movie dealing with the misidentification of who the titular Devils truly are. It is important to remember they should not be confused with the sinners themselves, even if the stark emptiness of the sets can’t help but exaggerate the misbehavior of the priests, crookbacked nuns and Christ humpers; all the while drawing as much attention towards the vileness of the human body as the Black Death Ghouls of Loudun wither and blister away.

All of these wretched creatures should be considered as nothing more than convenient distractions when it comes to determining who our fear and scorn should be directed towards, but when Russel is spending so much energy amping his audience up into a moral outrage, he seems to be inviting the same misidentification by the audience as we will soon witness those in Loudun adopt against their neighbours.

In Russell’s defence, it is not as if he isn’t up front early on who he believes his films villains are. He will identify two particular characters quite literally as “The Devils” as the title of the film comes on screen. It will appear over their faces, almost as if branding them with the red-hot scarlet of its letters. If this isn’t too on the nose for you, take note of the ominous music that swells as they begin to grin out at the audience. It is almost as if they are amused at how quickly so many watching will quickly forget about their sinister ways as soon as Russell ushers in his parade of horny priests and nuns. The spectre of sexual appetite and nudity (who even really needs the blasphemy part) has always been more than sufficient camouflage for those willing to duck behind it to do their dirty deeds.

Who these devils actually are, as one having any sense of history should know, are the men in power who have positioned themselves to be the beneficiaries of sin. These will be King Louis XIII, who we will first meet on stage re-enacting the Birth of Venus via ballet, wearing what might as well be a coconut bra. Then there will be a curmudgeonly Cardinal Richeleau, who can only yawn at the succession of royal plies he is being subjected to in the audience. These ridiculous men are the church and the state, on the cusp of consolidating power, about to bring the hammer of justice down upon its populace.

But as fond of torturing witches as they may appear to be, they are hardly here to eradicate sin as much as instigate it. They will become its conductor, and with a town so seemingly under command of their batons, they make easy work winding up the small rumbling of hubris and petty jealousy found inside of Loudun, into a squall of preposterous Satan worship in immediate need of exorcist intervention. They divide the populace against each other, make them rally against their own best interest to prove their virtue, even if this virtue is composed of little more than ignorance, revenge and self disgust.

Unsurprisingly, these will be the same virtues held by those who eventually would cry for the films banning and hopeful destruction. One can only imagine a solidarity forming between those characters cheering for the burning of Urbain Grandier (the accused priest who stands in the way of the States plans to tear down the protective fortifications of Loudun), and those in the audience who similarly would like to see this work of Russell’s give him some company upon the pyre.

Casting Oliver Reed as the tragic figure of Grandier, almost feels as yet another tactic for Russell to keep sympathy on hold for the character. At least until it is too late and our empathy is muted by the sounds of his shins cracking. Putting the likes of Laurence Olivier or Alec Guinness in place of Reed, and you would then have a character whose dignity would be ground in a civility that an audience might feel inclined to protect from being chipped away at by the State. But Reed’s bluster is something else entirely. He is the drunk sitting at the end of the bar boasting of past conquests, daring anyone to look at him wrong and risk the wrath of those knuckly hams he’s got swinging at the end of his arms. You might even be tempted to take a swat at him yourself.

But even when it becomes a little clearer that his character is operating from a Godly place, regardless of all the obvious moral failings he displays over the course of the film, it still may not be enough to help him. There is such a feral arrogance to the man, a baked-in hardness to how he looks at everyone who surrounds him, that it becomes easy for those so inclined to disregard what his noble intentions are, and instead focus on his bar brawler physique and face slippery with liquor sweats. He is not appetizing as a hero. Instead, he should be waiting for us outside of the pub to punch us in the stomach.

He is not an easy character to box into ‘good’ or ‘evil’ though. There is an initial fuzziness to his morality as his sins of pride and lust loom just as large in his personality as his need to be humbled beneath the eye of an almighty God. In early scenes, it seems that he is meant to be viewed as being cut from the same villainous cloth as the King and the Bishop of France. Scene after scene deepens his general unlikability. There is a violence to his sermonizing as he looks down upon his parishioners, walking in circles around those he demonizes as unworthy of God’s love, as if trying to dizzy them into agreement. Flaunting his holy physique around nuns, who pile into human pyramids to get a better look at him. And most callously, taking advantage of women under his tutelage, then discarding them when they confess how he has impregnated them. In short time, it becomes hard to image him as being a good man. It would be understandable if those watching may even consider him a bad man.

But unlike the King or the Bishop, as flawed a human as he may be, it is important to note that Grandier’s sins will always be earthly in nature. He is ultimately a man of the people. He is a human after all, his feet touch the same ground that the peasants walk upon, while the King spends his time pirouetting on stages and the Bishop has himself carted around in some sort of wheelchair contraption which keeps him always elevated at least a few inches from ever having to make contact with the earth below. These two will escape the world of God’s law unscathed, while Grandier seems to understand that a certain toll will ultimately be paid for the inescapability of his common sins. He fucks, he flaunts, he fights. And ultimately, he will burn.

Which is where the great horror of The Devil’s lurks. Grandier is a sinner, but so are all of us. His misbehavior, which would be easy for any to condemn him for, should be his binding agent to us. Sadly though, we will only discover his flawed heroism when it is too late, and he is contemplating the inevitability of his torture and death. His insecurities regarding this are when it becomes clear he is one of us. He worries he will turn his back on his God in these final moments. That he isn’t strong enough. That he is frightened of how much it will hurt. These are moments of frailty that are viscerally relatable. And as the breaking of bones, and branding of skin and cutting of tongues begins, he will scream from the horror of this physical pain, just like we imagine we would as well.

But unlike us, it may turn out that Grandier is a greater man than us all, no matter how poorly we may have first thought of him. Ultimately, he will not bend to the will of the state no matter what they do to him. And as he is strapped to the stake and set alight so that the skin begins to bubble from his head, he will remain unflinching in his ideals, while we the viewer can only look away. It is too difficult for us to even absorb the penance of his sins second hand. And as for these sins of ours, they are only now coming home to roost. For those foolish enough to allow the spectacle created by the church and state to distract and divide us from each other, the reward will be to watch those beautiful white walls of Loudun come tumbling down, and the charred landscape that has been hidden from our vision come into view. This desolate, smouldering world is what has been left for us.

And so it will be as the flames rise around the priest, those celebrating his death in the streets seem not to understand that it is them being burned as well. We will see the final moments of Grandier’s life from his point of view, looking out at the revellers, flames lashing up at their laughing and hysterical faces. And as the body of Grandier crumbles into ash, those in the street continue to dance, unscathed and unaware that these flames were also meant for them. Maybe just not on this particular day.

More Film Reviews

Whilst Wong is a very common name in Singapore and China, Cleopatra certainly isn’t! The name actually reveals the main inspiration for this film: the blaxploitation heroine – CIA agent… The Rage Part II is a 2023 British zombie horror, written and directed by Joshua Cleave. After studying film and television production at Leeds Metropolitan University, Joshua went on to… There are a lot of bad pants in this movie. Also, bad haircuts, bad sex and, whenever a chair is needed to hit someone over the head, or a table… I can’t believe that in my review of Fear Street: 1994, I forgot to mention the most important part of a successful slasher film: the sequel. Some slashers don’t always… Straight Outta Kanto here, reviewing for all you dedicated followers of fashion a movie that will knock your socks off! Or should that be… knock your “slacks” off? Slaxx is… In 1934, vaudevillian Will Hammer (real name William Hinds) diversified into the film industry. Hammer Productions Limited joined forces with Spanish entrepreneur Enrique Carreras to create Exclusive Films Limited, before…They Call Her Cleopatra Wong (1978) Film Review – Singapore’s First and Only Female Action Hero

The Rage Part II (2023) Film Review – All The Rage (Unnamed Footage Festival 666)

Cross of the Seven Jewels (1987) – Maybe Everything is Bad, But Half A Werewolf is Better Than None at All

Fear Street Part Two: 1978 Film Review – If you want Blood, you got it!

Slaxx (2020) Film Review – Revenge of The Killer Trousers

Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974) Film Review | Hammer Horror