Writer/director and the founder and artistic director of monochrom, Johannes Grenzfurthner is one of the most unique voices in cinema today. We were lucky enough to catch both Masking Threshold and Razzennest on the festival circuit, and it was off of his recent showing of Razzennest at the 2022 Fantastic Fest line-up that we were lucky enough to get some time to speak with him.

Official Bio from IMDB:

Johannes Grenzfurthner is a filmmaker, writer, artist, and performer.

He is the founder and artistic director of monochrom, an internationally-acting art and theory group. He is the founder of the movie production company monochrom Propulsion Systems.

His films deal with subversion, technology, nerd culture, politics, and the overall problems of life in 21st-century capitalism — for example his documentary features “Traceroute” (2016) and “Glossary of Broken Dreams” (2018), and his horror drama “Masking Threshold” (2021).

He is one of the most outspoken researchers in the field of sexuality and technology, and one of the founders of ‘techno-hedonism’. He is head of “Arse Elektronika” (sex and tech festival) in San Francisco, “Hedonistika” (food tech festival in Montréal and Tel Aviv) and host of “Roboexotica” (Festival for Cocktail-Robotics) in Vienna.

He gave talks at Fantastic Fest, SXSWi, O’Reilly ETech, FooCamp, Maker Faire, HOPE, Chaos Communication Congress, Google (Tech Talks), ROFLCon, Ars Electronica, Transmediale, Influencers, Mozilla Drumbeat Barcelona, Neoteny Camp Singapore, Columbia University, Carnegie Mellon University…

He and his projects have been featured in The New York Times, Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, Liberation, Spiegel, San Francisco Chronicle, CNN, Reuters, Slashdot, Playboy, Boing Boing, New Scientist, The Edge, the Los Angeles Times, NPR, ZDF, Gizmodo, io9, Wired, Sueddeutsche Zeitung, CNet, Toronto Star…

Johannes’ artistic and textual work are contemporary art, activism, performance, humor, philosophy, postmodernism, media theory, cultural studies, sex tech, popular culture studies, subversion, science fiction and the debate about copyright and intellectual property.

Can you please tell us a bit about how you first got interested in making film, what were some of your earliest influences?

I was a very classic kid of the 1980s. Obsessed with watching TV. First, there wasn’t a big difference for me between an episode of “Tom & Jerry” and a re-run of Peter Hyams’ Capricorn One. But that changed fast. I recorded it all on VHS, watched it repeatedly, and began understanding how movies were carefully constructed emotional machines. I wanted to try to create them myself, so I wrote down stories. And our family camcorder was a neat tool to play with. The challenges of tech were frustrating and rewarding at the same time. An example: We didn’t have two VCRs, so I always had to edit the video while shooting. If a take, let’s say, of our space-shuttle-on-strings-movie was terrible, I had to rewind the tape and re-record the take, overwriting the bad take. That always created these magical bursts of interference and micro-fragments between scenes because the rewind function wasn’t precise enough. I’m still in love with these unwanted visual leftovers. While editing my nerd documentary Traceroute (2016), I digitized many of the films I shot as a kid—and I wasted hours analyzing them frame-by-frame. Fascinating. Material semantics, hell yeah!

Can you please tell us a bit about the principles behind ‘techno-hedonism’ as well as whether your studies in the subject are represented in your filmography?

The first efforts to create artificial intelligence date back to the early 1960s when Armstrong was plodding around in the Mare Tranquilitatis. Modernity had invested its victory prey into moon rocks, and everything seemed possible. The first artificial brain was foreseen to exist at the turn of the century; it’s 2022, and I do not even trust my toaster. That’s where techno-hedonism comes into play. How can we have fun with technology? And how can technology have fun with us? What is a great way to deal with technology in a non-toxic, non-exploitative way? I haven’t yet created any movies that specifically deal with techno-hedonism besides parts of my doc Traceroute, but there are a couple of ideas I have in mind. Let’s see where they will take me.

As your approach to film could be classified as unconventional, can you discuss how a production under monochrom would work? For example, do you avoid the use of storyboards, and how much of the final story comes together in the editing process?

It really depends on the project. monochrom, the art group I founded in the early 1990s, is more like a collective than a production company. We all have our interests and passions, and we try to put them to use. I was always the person in our group interested in narratives. I love film because it’s such a low-entry no-bullshit form of art; it doesn’t need to be explained because we all grew up with it. We understand the cultural grammar of cinema. That doesn’t mean there aren’t incredibly pretentious films that make it somewhat hard for you to grasp them. Of course, there are, and I use this in Razzennest, but going into a movie theater or watching a film at home doesn’t have the same cultural barrier as a gallery show, a live theatre, or a poetry reading. The conventions of cinema are more porous, for lack of a better term.

In Masking Threshold, what inspired you to explore auditory hallucinations? And what do you think our relationship is to the noise that surrounds us and whether it can have negative effects?

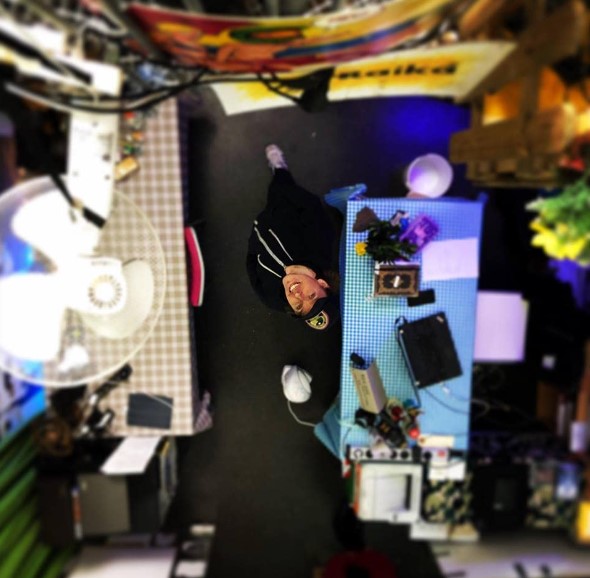

First, it wasn’t clear what should drive him crazy. It needed to be something in his head… and then it hit me: Tinnitus. I only had it for ten minutes in my 20s, which was terrifying enough that I can still remember it. So, I did a lot of interviews with people suffering from hearing deficiencies. I wanted to learn and understand as much as possible about it. And I wanted to combine the conventionality of horror film (based on a new reading of H.P. Lovecraft) with a radical experimental aesthetic, underscoring the film’s soundscape. Masking Threshold is primarily shot with macro and loupe lenses. For example, things only a few inches tall become full screen. This makes it possible to enlarge the narrow space of the nameless protagonist’s hobby room almost to infinity of miniaturization. Everyday things like greasy pizza, ants, or egg yolks suddenly become monstrous and otherworldly. It’s almost as if my actor Ethan Haslam’s voice and the objects on his desk merge into an alien, psychoacoustic landscape through which the viewers were narratively moved.

Razzennest pokes fun at both filmmakers and critics alike, what are your thoughts on the role between the filmmaker and the critic? Were Manus and Babette exaggerations of bad characters you can find in the industry or based on people you have encountered (not asking to name names)?

Hell yes. I would call Oosthuizen, Cruickshank, and the other characters “emulations” or “simulations” of people I know or have read about; pastiches of existing characters. One critic wrote that he disliked the film because he had never met or seen people in the industry that act like the people I portrayed. That’s why he dismissed Razzennest as a cliché. Boy, I wish he was right. It would make the world a better place. Ha! Indeed, I use satirical exaggeration, but sometimes I even used exact quotes from directors and producers and put them into Manus’ maniacal outbursts. He is like Kinski and Herzog run through Seth Brundle’s teleporter.

What was the inspiration behind the horror elements of Razzennest? Was any of it based on real-life incidents?

Oh yes. Razzennest allowed me to realize my decades-old dream of making a film about the Thirty Years’ War and its endless atrocities without needing a budget of millions of dollars to depict the war’s bloody significance. I read a lot of papers about the conflict, and all incidents in the story are based on real-life descriptions of cruelty that really happened. I wanted to bring the specters of the past into the present and let them run havoc.

How would you classify your films Masking Threshold and Razzennest? Would you call them horror or would you be more inclined to describe them as something else?

They are definitely horror films. I don’t shy away from calling them genre films. I love genre films. Razzennest is both an homage and vivisection of genre. Masking Threshold and Razzennest have very different flavors, though.

I think when writing Razzennest, I incorporated a lot of positive and negative experiences I had when promoting Masking Threshold.

Who are some of your favourite current filmmakers? Who has you excited for the future of cinema?

So many! SO MANY! And even the ones that I don’t really get are a constant inspiration to me. For example, Nikolaus Geyrhalter. His film Home Sapiens was the aesthetic template for the kind of arthouse film that I wanted to satirize in Razzennest. I really didn’t like it, but then I used it as a significant source.

What are you currently reading, watching, and listening to?

I wish I had more time to read fiction. Most of the books I read are in preparation for projects. I still have all the medical textbooks about audiology sitting around that I bought for Masking Threshold. And all the history books about the Thirty Years’ War.

Concerning films and TV shows: I am pretty good at posting new things I discover on Twitter and Facebook, so please follow me there for my daily brain dump. (https://twitter.com/johannes_mono)

Do you have a personal motto you try to adhere to when making art?

Keep going, or the clowns will eat you.

If people wanted to keep up with your work, what is the best way for them to do this? Also, are there any current or upcoming projects you would like to plug?

You can easily find me (shout-out to my crazy last name) on the intertubes. And concerning new projects: I am working on a documentary called Hacking at Leaves, which will hopefully be finished early next year. It’s not a horror film, but it deals with the real-life horrors of US colonialism, genocide, COVID – and hackerspaces. But honestly, I never know where life will spit me, to use an old Austrian idiom. I had the idea for Razzennest on January 31, 2022. And I finished the film in early June 2022. Whenever I can, funding wise, I try to follow my instinct.

More Interviews

Thomas Burke is an award-winning filmmaker and editor based out of Austin, Texas. He has spent over the last decade freelancing in various production roles including film directing, acting, producing… No stranger to the horror genre, Chad Ferrin found his footing in the film industry as a production assistant on such films as Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers and… Mathew Meyer’s is an American artist best known for his traditional Japanese style representations of Yokai, drawn with loving detail to the woodblock printing technique of ancient Japan. Mathew regularly… With the launch of the Jan 20 launch of FRIGHTFEST SATURDAY SCARES WITH ALAN JONES on Fast TV channel NYX, Alan recounts his rise to journalistic prominence – from stealing…Interview with Director/Editor Thomas Burke – Found Footage Aficionado

Interview with Filmmaker Chad Ferrin – Writer & Director of the upcoming film ‘Pig Killer’

Interview: Matthew Meyer “There’s Essentially a Yokai for Every Occasion”

An Interview with Alan Jones – Famed Film Journalist