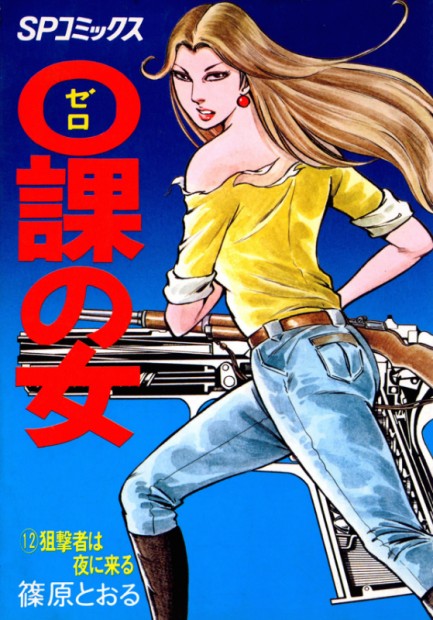

Despite other studios seeing success with their own manga adaptations, Toei had always been hesitant when taking such a leap. That all changed in 1972 with Toru Shinohara’s Female Prisoner Scorpion. With its action and grit honed by one of the upcoming masters of action manga, complemented by director Shunya Ito‘s own political and avant-garde spin, the adaptation was a runaway hit, spawning a series of five films. Following the success of Female Prisoner Scorpion, it was perhaps natural that Shinohara’s new manga series Zero Woman would be next on the list to receive an adaptation courtesy of Toei. Released in May 1974, Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs would become a late genre-defining entry into the pinky violence stable, which was entering its twilight years by this point in time.

Wearing knee-high boots, a long red coat, and an impeccably painted pout, Rei (Miki Sugimoto) casts a beautiful, yet imposing figure. When dancing at a club, it’s not long before she catches the eye of a foreign patron, who quickly tries his luck sweet-talking her in clunky Japanese, whilst also attempting to ply her with copious amounts of whisky. Once he has her back to his room, he dumps the seemingly unconscious Rei on the bed before opening a suitcase full of torture implements. However, it is revealed that this was all an elaborate ruse carried out by Rei, who is, in fact, an undercover cop. She has been stalking this serial killer for some time and has made it her personal mission to bring him to justice. After a struggle ensues she eventually kills him, but to her surprise, her target is actually a foreign diplomat, and the potential political outrage of his execution leads to her being abandoned by the police and thrown behind bars without so much as a trial.

In the meantime, petty criminal Yoshihide (Eiji Go) has just been released from prison and reunites with his gang who have been waiting for him by the gates. Not one to turn away from a life of crime, the roaming gang is quick to find their next target: a couple who have parked their car up in the wrong part of town. The gang descends upon them like jackals and quickly drags the woman (Hiromi Kishi) away to gangrape her, before eventually killing her boyfriend. From there, they take her back to their back-alley hideout and attempt to sell her to their “sister” Sesum (Yoko Mihara) to pimp out. Sesum immediately recognises the girl as Kyoko Nagumo, the daughter of Zengo Nagumo (Tetsuro Tamba) – a prominent politician who is in the running for the office of prime minister. After realising Kyoko’s value, the gang quickly update their plot to that of kidnapping and extortion – demanding a 30 million yen ransom for her safe return.

Given the politically sensitive nature of the situation, the regular police are deemed unsuitable for the case. Instead, it is passed over to Section Zero: a deep undercover secret police division that deals with cases where extrajudicial force is required. Zengo can’t afford news of his daughter’s kidnap to come to light, lest it damage his political career, so demands not only the return of his daughter but the killing of all of those responsible. To carry out their missions, Section Zero requires agents who are willing to do anything, and most importantly, who technically do not exist. With Rei hidden away in prison without any chance of release, she is approached for the role; and given freedom in exchange for becoming the nameless “Zero Woman”. It is up to Rei to then carefully insinuate herself into the gang and gain their trust, in an attempt to bring it down from the inside and return Kyoko relatively unharmed.

Much like Shunya Ito’s Female Prisoner Scorpion films that came before, director Yukio Noda, and writers Hiro Matsuda and Fumio Konami, use the manga source material of Zero Woman more as a springboard to tell their own story. In their hands, the original pulpy action-packed homage to “outlaw detective” films like Dirty Harry becomes a deeply political commentary on society; taking on a new nihilistic tone. Rei’s origin is totally unique to Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs; in the manga, it is assumed that Rei willingly acts as the “Zero Woman”, driven by her desire for justice; whereas here she is not given a choice. In order to infiltrate the kidnappers, Rei must allow herself to be raped, lest they suspect that she is an undercover cop. Whilst in the manga she has to occasionally use her body to her advantage, the fact that she is a somewhat unwilling agent in the film feels like Section Zero is just as culpable for her rape as the kidnappers. In the manga, you always feel like Rei has her plan sorted and is waiting for the right moment to strike, but in the film it feels like she has been thrown to the dogs by Section Zero as an expendable tool. Similarly, the film’s story is also unique. Taking inspiration from a story from the manga where the chief of police’s daughter is kidnapped, Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs shifts this to the daughter of a politician, enabling its political commentary to go straight for the jugular.

Though one of Pinky Violence’s most popular actresses, Miki Sugimoto often had to spend most of her prior career playing second-fiddle to her more bombastic co-stars. Whereas Meiko Kaji and Reiko Ike got Female Prisoner Scorpion and Sex & Fury respectively to make their own, Miki had to settle with the lead in just one of seven Girl Boss films. Fortunately, she was finally given that chance with Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs, and she certainly does not waste it. Not only does she arguably put in the performance of her career, she also does so with an extremely complex and difficult character.

At first glance, Rei is a tigress – willing to kill if that means getting justice. However, after her arrest that all changes. She is declawed and forced to submit, and the fire of determination that burnt so brightly is subdued and slowly converted into flames of hatred. To carry out her mission, Rei has to build an impenetrable outer shell, hiding any emotion behind a cold façade. She adopts an almost robotic demeanour, not only as a method of infiltration but also as a coping mechanism for her abuse. Somehow, Miki Sugimoto can take the seemingly emotionless husk of a woman and manage to convey inner strength, sorrow, and rage. Despite remaining ever cool and never even allowing her calm voice to crack, the audience is at one with the burgeoning rage slowly boiling inside her.

The early 1970s were a tumultuous time politically in Japan. The country of Japan (both its people and the government) directly opposed the U.S. war in Vietnam, however, the U.S. still had active military bases in Japan – especially in Okinawa which was still under U.S. occupation. The fact that the U.S. was using what was essentially Japanese land as a vital supply route for their war effort, understandably led to massive outrage and tension nationwide. Daily protests were held outside of U.S. military bases for the entire 20-year duration of the war, and by the 70s, riots were becoming more commonplace. In particular, the Koza riot in Okinawa City leads to 3000 Okinawan citizens clashing with the U.S. military police.

Being produced in 1974, Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs is well-positioned to take a retrospective look at these events, with the U.S. occupation of Okinawa ending in May 1972, and the U.S. officially withdrawing from the Vietnam war altogether in January 1973. Director Yukio Noda wastes no time in making his political statements, with the first major one coming just minutes into the film with the gangrape of Kyoko. As each member of the gang approaches Kyoko to rape her, the screen repeatedly jumps to the image of a U.S. cargo plane flying overhead at the point of penetration. The phallic symbolism of the plane’s fuselage is clear to see, as is the metaphor for the U.S.’s rape of Vietnam. However, given the period, there is an additional angle to this imagery: the cargo plane would have been leaving Japan post-Vietnam, carrying supplies back to America. Whilst people can focus their anger on the U.S. actions in Okinawa and Vietnam, perhaps even using them as a scapegoat for Japan’s societal ills, the fact of the matter remains that this scene shows Japanese men raping a Japanese woman – no U.S. involvement is necessary for this assault. Both of these points are further highlighted by Yoshihide wearing a U.S. Navy surplus jacket.

Further allusions to this commentary return for the finale of the film, where a violent shoot-out takes place in an abandoned U.S. military base. The spectre of the U.S. military presence hangs thick in the air (spectre being the prominent word as the base is a literal ghost town, littered with discarded paper and a howling gale blowing throughout.) Once again, the violence shown here is purely Japanese people killing each other. When Yoshihide first arrives at the base, he is immediately reminded of his childhood when his mother worked as a prostitute in Okinawa City. She would have no doubt slept with American servicemen, and it seems that, in the face of death, Yoshihide wants to blame his own wicked actions on his upbringing and the foreign enemy to absolve himself of responsibility.

Alongside the venomous political commentary of the early 70s, Noda is not remiss to overlook more general criticism of modern-day Japan. Bitter themes showing political greed, corruption, and selfishness; alongside police brutality and authoritarianism, are all clear to see. Even with Section Zero’s extreme methods, the manga always showed them as a force for justice. However, with Zengo’s involvement, the chiefs at Section Zero are quick to think of the potential favours which could be offered if Zengo does indeed become Prime Minister shortly. Thus, Section Zero effectively becomes his personal army, crossing the line from a secret extrajudicial police force to a borderline fascist organisation – at one point they even announce themselves as “Nagumo’s men”. Nonetheless, Noda’s commitment to nihilism means he goes far beyond criticism of Japan’s right-wing institutions: in Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs, every facet of society is a target, and even the left wing has representation in Noda’s shooting range. This comes in the form of Kyoko’s lover, who is a Zengakuren member. The Zengakuren were a group of radical left-wing student protestors – predominantly linked to the Japanese Communist Party – who was known as much for their violent riot tactics as their iconic “Zenkyoto” coloured helmets. Her lover is shown as weak and whiny and is quickly dispatched by Yoshihide and his gang before ever managing to land a punch.

For all its criticisms of the cruelty and selfishness of society, and its grandiose derision of politics, it has to be said that Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs absolutely indulges in the same culture it so willingly condemns. The film is unabashedly brutal and has no qualms in both the depiction and exploitation of sexual violence against women. One could claim that, only by showing such acts in their natural savagery, can you ever truly tackle the subject; certainly, such shock tactics have been an effective tool throughout the history of cinema. On the contrary, there is no doubt that Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs goes far beyond the limits of good taste and begins to verge on torture porn at several moments throughout its runtime.

Perhaps the most notorious scene of the film shows Rei tied to a pillar and continually beaten and raped by Yoshihide and his gang for hours on end. All the time, the lens of the camera pores over Miki Sugimoto’s body like the grimy hands of a rapist. Images of her scarred breasts and bruised body fill the screen; the tone feeling less so of horror, but more of admiration – choosing to marvel at her wounds, almost like a beautiful tattoo on her beaten flesh. Further highlighting the exploitativeness of this scene is the fact that it was chosen to feature on the film’s various posters, even going so far as to sit front and centre on the Toru Shinohara-painted re-release version.

Fortunately, Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs isn’t entirely wall-to-wall suffering, and the audience is occasionally offered some respite through its action scenes. This is where the film truly commits to recreating the manga, with pulpy, almost cartoonish, levels of extreme bloody violence torn straight from its pages. With his previous experience helming much of the Delinquent Boss biker gang series, Yukio Noda knows how to execute eye-catching action, and is afforded a comfortable budget to go all-in with explosions and car chases. The finale showdown at the abandoned military base is particularly satisfying and provides a much-needed palate-cleanser after the bleakness that preceded it.

At first glance, it is easy to disregard Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs as a victim of Noda’s all-consuming cynicism, with a vague message buried somewhere beneath an unfocused indignant rant at the world as a whole, and a surrender to mean-spiritedness. However, I think it is best to view the film not as a condemnation of society, but more as a reflection. Though excessively extreme, such an approach feels necessary to truly capture the lofty levels of nihilism required to broach such a subject. To create a true reflection, Noda himself must choose to wallow in the filth; embracing the most disquieting facets of pinky violence and Japanese exploitation cinema, before vomiting them forth onto celluloid. Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs has no moral compass because it positions itself as the ultimate unwavering depiction of an immoral society.

The difficult, and perhaps unsettling, question has to be: what makes Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs so captivating? After laying all the bleakness and nastiness bare, it feels somewhat strange now to say that Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs is a brilliant film – even enjoyable as a whole. What does that opinion say about the state of the viewer’s psyche? They Call Her One Eye is perhaps comparable in its bleakness, but at least that has the benefit of being a true rape-revenge flick; I wouldn’t necessarily call Rei’s story one of revenge.

I think in the end, it all comes down to Miki Sugimoto’s delicate portrayal of Rei: the ultimate product of abuse (by society, her fellow man, everyone.) Is Rei a hero? A villain? A victim? A survivor? Does she truly bring justice? Does she further the downfall of modern society? No one can say, because she is the “Zero Woman”. She is nothing. She represents every woman who is left out of society. The “Zero Woman” could equally be a homeless person, a drug addict, a prostitute, a runaway, or even a Vietnamese villager; her experiences throughout the film are not unique to an undercover detective. The audience can clear their heads with a suitably cathartic ending, but nothing has been achieved. That is what makes Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs such an irresistibly bleak car crash to observe.

A new 4K restoration of Zero Woman: Red Handcuffs has recently been released by Neon Eagle and is available to purchase from Cauldron Films here.

More Film Reviews

Strike of the Tortured Angels is a fairly obscure, though not totally unknown film; appearing in the 1980s as part of a wave of Asian films brought over to the… Combine the carnage of slasher films and socially relevant commentary, and you’ve got the recipe for a horror film that cuts deep, literally and figuratively. For this writer, Initiation does… “The Lord giveth. The chamber taketh away.” The Ackerman’s have a family business: torture. When older brother Tyler (Seth O’Shea) goes missing, his sister Ava (Jessica Vano) is left in… If you are a lifelong fan of horror, then you know full well that endless sequels and remakes are just a part of the game when it comes to film…. Aspiring millennials and their first-world problems are inherently absurd, particularly when their bourgeois existence is challenged, or at least that’s what Who Invited Them relies upon as it attempts to… The Curious Dr. Humpp (La Venganza del Sexo) is a 1969 Argentinian sexploitation horror, written and directed by the prolific Emilio Vieyra – well-known for his work grounded in exploitation…Half-Breed Julie AKA Strike of the Tortured Angels (1974) Film Review – Korea Takes On Pinky Violence

Initiation (2021) Film Review – Pledges to Challenge Slasher Expectations

The Chamber of Terror (2021) Film Review – Canada’s Evil Dead

V/H/S/85 (2023) Film Review – Be Kind, Rewind

Who Invited Them (2022) Film Review – Unexpected Guests

The Curious Dr. Humpp (1969) Film Review – “Sex dominates the world! And now, I dominate sex!”

Hi, I have a borderline obsession with Japanese showa-era culture with much of my free time spent either consuming or researching said culture. Apparently I’m now writing about it as well to share all the useless knowledge I have acquired after countless hours surfing the web and peeling through books and magazines.