Ivy, played by Brigitte Lin Ching-Hsia, is a Taiwanese student living in San Francisco. She shares a dormitory with other students of her diaspora. The pupils consume most of their American life in gossips, anecdotes and leisure. For Ivy, who appears to be a relatively serious character, chatters are secondary to spending time with pals Joy and Louie. Joy demonstrates suicidal inclinations, leading Ivy to secretly request her brother to fly to the US to see her. Chiu-Ching, Joy’s brother, appears, but his arrival advances the increasingly complex predicament of the quartet.

Initially, the creation of a love triangle appears to be the central conflict. Chiu-Ching and Ivy effortlessly fall in love, their compatibility facilitated by the former’s straightforward behaviour. As the narrative proceeds, love becomes the driving force to every movement of the quartet, and additional relationships of various magnitudes are either witnessed or hinted at. Ranging from plausible to alarming, the chains create an intricate web, appropriating the English title of the movie.

The real complexity lies in the mental instability of Joy and Chiu-Ching. The siblings refuse medical treatment and create trouble for Louie and Ivy. Joy’s refusal to accept the creation of rapport between her brother and friend is not without merit, but it is her lack of communication that jeopardizes the delicate string of equilibrium preserving their collective life. Yet again, every direction the movie takes is driven by love, and ultimately it leads to a brutal massacre.

Patrick Tam Kar-Ming’s status in the west primarily pivots on his mentorship of Wong Kar-Wai, but in his native Hong Kong, he is recognized as an influential director. One of the leading lights in the exemplary Hong Kong New Wave, he, alongside the likes of Tsui Hark, Ringo Lam and Ann Hui, rewrote the way movies were created in Hong Kong. Tam’s signature traits encompass hyper-stylization, cautious assignment of the palette and the inclusion of thrills, chills and violence in midst of intricate romantic dilemmas.

“Love Massacre” ticks all of the above-mentioned traits. While the only available version is a censored copy with reduced violence, it survives to gradually evolve into a thrilling slasher. Generating impact even before the opening credits, the film clenches the spectator with an icy grip, juggling love and fear with remarkable capability, with occasional junctures detecting a coalition of the two emotions in the psyche of the characters.

Tam started his movie career by creating a rather contemplative wuxia film in “The Sword,” and for his sophomore work, he shows a recklessly experimental self. He twists and turns genres, blends love and horror, creates an ominous atmosphere out of sensibly chosen colours contrasting each other in a muted scheme, and assigns likewise dreadful electronic music to top it up. The final concoction is strange yet flavourful.

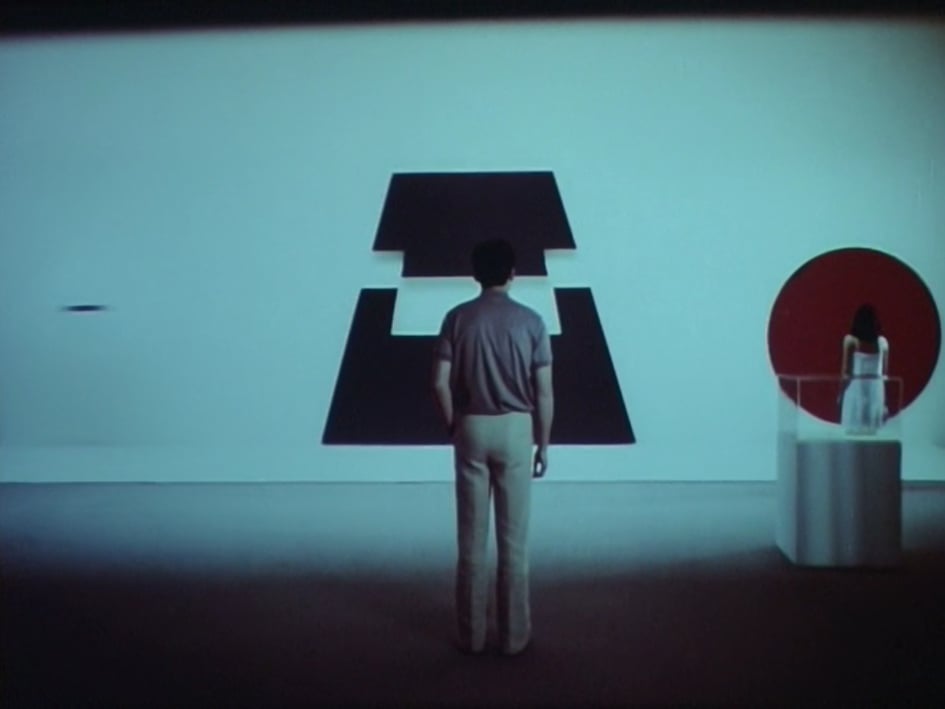

At times, even Tam comes across to be unaware of the narrative direction, and when he finalizes an ending, the censor board decides to viciously massacre (pun intended) each murder scene into an editing nightmare. Tam’s characters, too, hardly comprehend the future they are about to dive into. In a fantastic scene, Louie and Ivy visit an art exhibition. The art displayed in the gallery is rather abstract. They are conceptual and rely on their form and colours. Louie and Ivy are focused on a different notion of abstraction: fate seems sinister and they possibly neither understand nor care about the art they glance at.

Acting is a department that leaves a lot to be desired. Brigitte Lin is expectedly terrific and Chang Kuo-Chu does the best fulfilling the exaggerated murderous stares and expressions allocated to Chiu-Ching. Charlie Chin’s Louie is a real disappointment, with his acting inflexible and unstructured. Tina Lau is perhaps relatively better, but her performance as the volatile, unhappy Joy fails to add to the experience. Ann Hui, another pioneer of the Hong Kong New Wave, has a small yet significant role, in which she proves better than half the cast.

“Love Massacre” is a conceptual tragedy. Not everything observed in the film makes sense. Human validities of assessment and ethics, too, are blurred by Tam’s splendidness. Through a deeply abstract idea, the director overtakes the need for logic in the film. In a way, the film resembles the work of Godard: forfeited emotions return through unimaginable routes. Violence is crucial to the movie’s presentation, but even violence, blood and slaughter fail to reach absolute status in the film’s principles of love warfare. Love triumphs over violence and therein lies the true tragedy of the characters.

“Love Massacre” is censored, and suffers from a range of disappointing acting performances. Yet it is a chilling experience, even on multiple watches. Tam’s minimalism is the movie’s trump card, which binds the distanced, muffled world into a horrid hotspot for violence. Is it a masterpiece? Possibly it is. What is certain is the fact that “Love Massacre” is Hong Kong New Wave at its zenith, with genres liquefied by the raw talent of directors such as Tam.

More Film Reviews

“We are the children. It’s a pleasure to receive you.” Remember how we always question why alleged alien abductees live to tell the story but don’t have the evidence to… “In a large isolated cellar, a mysterious aristocratic woman begins torturing a man while videotaping it. The torture escalates as we find out the secrets the man holds inside of… Just the facts ma’am. Or so one might expect the detective keeping vigil outside of the house in a rumpled raincoat to ask. He chews on his obligatory cigar and… The breakdown of friendships into the realm of horror has always been a theme fascinating me; the amount of paranoia needed to turn an object of comfort into terror being… Fans of the horror are very much aware of the amount of subgenres that have been birthed out of the general moniker of being called horror. However, out of all… Vampires vs. The Bronx, Night Teeth, and now J. J. Perry’s Day Shift: someone over at Netflix is into the prospect of investing in vampire horror comedies of varying quality….The Alien Report (2022) Film Review – Close Encounters Done Well

Xpiation (2017) Film Review – Strap in for Some Good Old Fashioned Torture

The Amityville Horror (1979) Film Review – An Investigation Into The Chopping of Wood and Whether or Not We Have Any Reason to be Frightened

Bleed With Me Film Review – Lets Make A Blood Pact

30 Best Horror Comedy Films – From Classic to Cult

Day Shift (2022) Film Review – A Fun Vampire Comedy That Doesn’t Quite Hit the Jugular