“I have varicose veins and I hate to shop at malls,” said the caller on the infomercial.

It’s a throwaway line in John Schesinger’s Pacific Heights, probably pulled from an actual ad airing in the Bay Area at the time. If not, it’s shockingly realistic. But in the context of the film, it’s just there to show that Mathew Modine, the young urban professional who has had his life upended by con man tenant Michael Keaton, is passing out in front of television.

Still, it’s a line that celebrates home shopping, home convenience and buying things you don’t need.

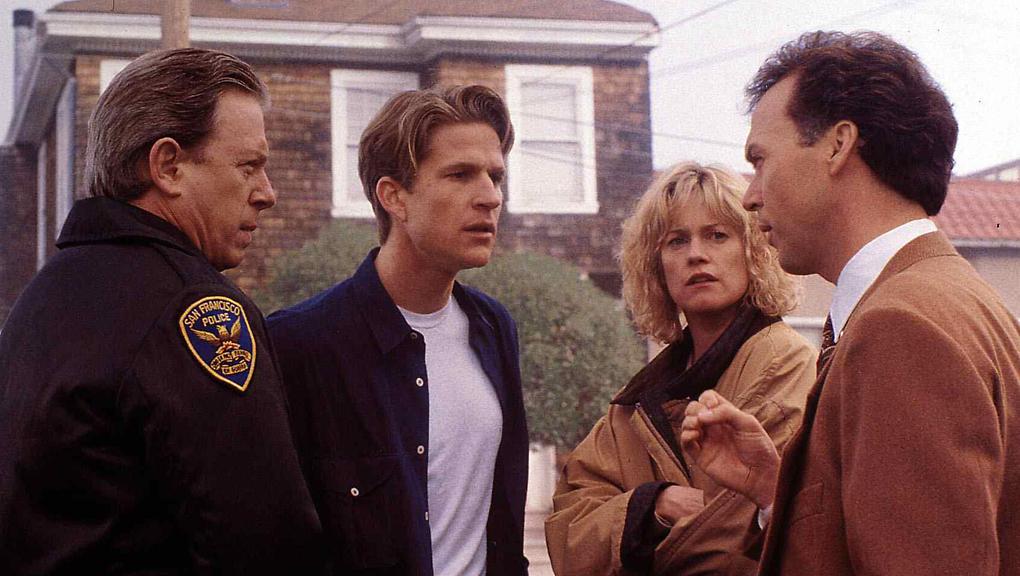

Drake Goodman (Modine) and Patty Palmer (Melanie Griffith) have bought something they don’t need. They purchased a 19th century San Francisco building in the desirable neighborhood of Pacific Heights (though anyone who has been to San Francisco knows the house is not actually located there). The building has two other apartments they can lease. Goodman thinks he’s found the perfect tenant when Carter Hayes (Michael Keaton) shows up with a roll of 100s and promises of a wire transfer for the full amount.

But the transfer never comes, and the rest of his story is just a scam to use California’s renter’s laws in his favour to drive Modine crazy and assume his identity.

Behold the horror that are eviction laws! In reality, they’re probably the scariest notice you can receive, and they’ve taken matters to a special level of awful during the pandemic. In the movie, they’re a nuisance the villain uses as a weapon to terrorize his wealthy landlord.

While Modine and Griffith stand to lose a lot, it never feels like they wouldn’t end up on their feet. While Modine ends up in jail briefly, to be frank, it’s deserved. Keaton’s a monster, and he’s doing it with a sick bit of glee, but he genuinely would wind up homeless otherwise, if not worse.

It’s always interesting when a film meant to appeal broadly inspires outrage.

Pacific Heights performed well, but it wasn’t without its detractors. Most notably of whom was Roger Ebert, who coined “yuppie horror” for his review. He may not have realized he was identifying a burgeoning subgenre, in which selfish, upwardly mobile young white (an early scene specifically shows Griffith refusing to rent to a black man) wealth are suddenly threatened by a lower class. It became a staple in the early 90s, with films like Unlawful Entry, Malice, Shattered, Guilty As Sin and Alan J. Pakula’s unfortunate final film, Consenting Adults. This was what you’ve heard some boomers describe as, “When movies were made for grown-ups.” Rather, they’re mostly just a few production values and high-end cast removed from whatever Cinemax was running with Jim Belushi.

Heights was the first that struck a nerve. The general consensus was: Why were we meant to care about these assholes? Anytime the stock market strikes disaster as it did two years prior to Heights’ release, there isn’t a lot of sympathy for the obscenely wealthy. And Hollywood had no interest in greenlighting anything that channeled public outcry like The Big Short in 1990.

Why indeed. Schlesinger does his damndest to make them sympathetic, even making Griffith suffer a miscarriage. Modine continually acts petty, takes up problem-drinking and gets irrational to the point where his own actions further jeopardize his not-wife (the film makes it abundantly clear that yuppies are too busy and important to settle down). Griffith doesn’t fare much better. She’s certainly the more proactive of the two, and ultimately it’s her that tracks Keaton to a hotel. She flips the tables, charging exorbitant room service until he’s arrested, and she steals money from his room that she leaves for a maid. However, on second thought, she keeps a good chunk of it for herself.

One would think, with such unlikeable leads, it’d be hard to generate much tension at all, but the film does have a secret weapon. Michael Keaton, fresh off Batman, taps into a similar kind of eccentricity that Bruce Wayne had, but far more cold-blooded. Both roles have him carrying a dual persona, and his affable charming tenant harbors a violent sociopath with a surprising restraint. In the few instances he flies off the handle, he’s downright terrifying. He never lets you know more about him than he wants, and it’s to the film’s credit his backstory is clouded for the majority of the runtime. Mostly, it lets Keaton just show you who he is.

And he’s got an entire movie to carry. When he’s off screen, apart from some choice bit parts from veterans like Dan Hedaya, the movie simply doesn’t work. A dream sequence that Modine experiences feels more in line with a bad Twin Peaks knockoff.

Interestingly, the aspects critics picked apart upon Heights’ release have aged unintentionally well. Mathew Modine’s performance was ridiculed for overacting (and he does), claiming that his behavior in the film’s last half is as unhinged as Keaton’s. For a role meant to be an everyman, it’s a weird choice. But considering the same generation of Reagnites inspired Patrick Bateman’s serial killing stockbroker, today it reads true, like the kind of tantrum these people would have before they had cameras in their phones.

It’s safe to assume Schlesinger knew that going in. The aforementioned “black” scene isn’t without self-awareness, and it is revisited later. And the director had a history addressing class issues previously, adapting the English novel Billy Liar early in his career.

The appeal of the project is understandable. The output isn’t.

This article was originally written by Kenny Hedges for Grimoire of Horror.

More Reviews:

Cube (2021) Film Review – Japan Beat Hollywood to the Punch

The term “remake” is often met with blatant vitriol and is usually accompanied by assertions that Hollywood is either running out of ideas or is cashing in on the nostalgia…

Carved: The Slit-Mouth Woman (2007) Film Review – A Dark Portrayal of Child Abuse and Urban Legend

While this film is initially easy to write off as superficial with cheaper scares, I feel that it deserves much more credit and a deeper dissection. With a severe spoiler…

Razzennest (2022) Film Review – A Unique Experiment in Aural Terror

“South African enfant terrible filmmaker and artiste-cineaste Manus Oosthuizen meets with Rotten Tomatoes-approved indie film critic Babette Cruickshank in an Echo Park sound studio. With key members of Manus’s crew…

The Breach (2022) Film Review – Into The Breach Once More

The Breach is a 2022 Canadian cosmic horror, written by Nick Cutter and Ian Weir, and directed by Rodrigo Gudiño. The film is based on the novel The Troop, originally…

Smiley Face Killers (2020) Review – College and University Bros Beware!

‘The smiley face murders’ exists as a modern urban legend, a way to explain the mysterious drowning deaths of college/university age men. This comes from a multitude cases where near…

Ghost Lab Review (2021) – A Scientific Ghost Horror from Thailand

Ghost Lab is a supernatural Thai horror that has an extraordinary, unique story accompanied by a massive twist. However, it has an unnecessarily long run time of almost two hours!…