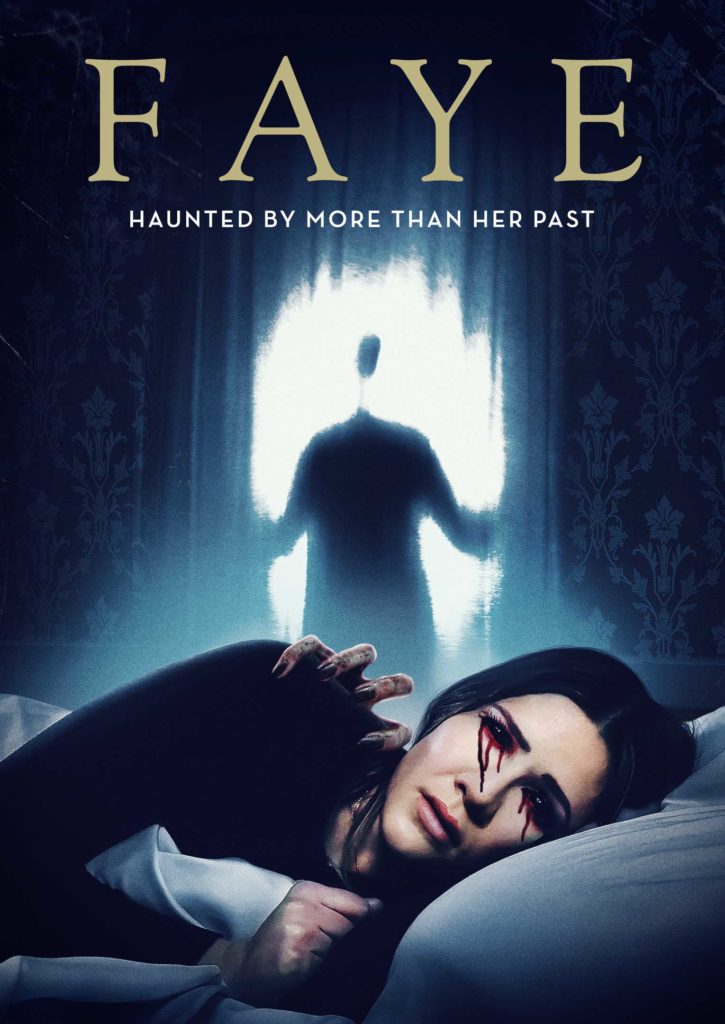

KD Amond and Sarah Zanotti’s Faye might be the must-watch indie horror of the year. Shot on an iPhone with a total crew of five people, almost entirely built around Zanotti’s go-for-broke performance, Faye is a one-of-a-kind tale of grief, a masterclass in overcoming budgetary restrictions, a deeply terrifying psychological horror, and another confirmation of the adage that comedy equals tragedy plus time.

Faye Ryan is a grief-stricken “self-care” author who talks to her dead husband as a way to keep his memory intact. Being pressured into writing a new book by the powers that be, she goes on a writers’ retreat in a house on the Lousiana bayou. Turning to binge drinking, Faye begins to lose time and frequently wakes up in the bathtub after intense panic attacks. Soon enough, the constant interruptions – fear-inducing blackouts and strange noises – make her believe that the house is haunted.

The film is structured into chapters that mirror the five stages of grief. The beginning sees Faye in almost complete denial of the fact that her husband is gone, threatening to jump her current psychiatrist for one that will forgo the issue of loss she is facing. In the second chapter, anger starts to seep in, with Faye taking a passive-aggressive stance on the supposed haunting and posting a potentially career-ending video on Instagram. Depression is a constant but becomes almost suffocating, the movie never gives the audience time to process the constant stream of thoughts. There is virtually no guarantee that Faye will ever get to the bargaining and acceptance stages because she constantly refuses help and increasingly succumbs to her dark ideations.

Amond and Zanotti are co-founders of AZ If Productions, both sharing a background in music and currently working on several film projects. Amond focuses on “female-driven comedy, horror, thrillers, and dramatic thrillers”, having directed movies like Five Women In The End and Rattlers, while Zanotti has previous experience with delivering explosive moments and performing subversive reinterpretations of country music lyrics (such as her music video for Justify, or her hilarious appearances in John Crist’s “Country Lyrics in Real Life” series). Both came up for the idea for Faye while watching a movie and describe themselves as “each other’s yes men”.

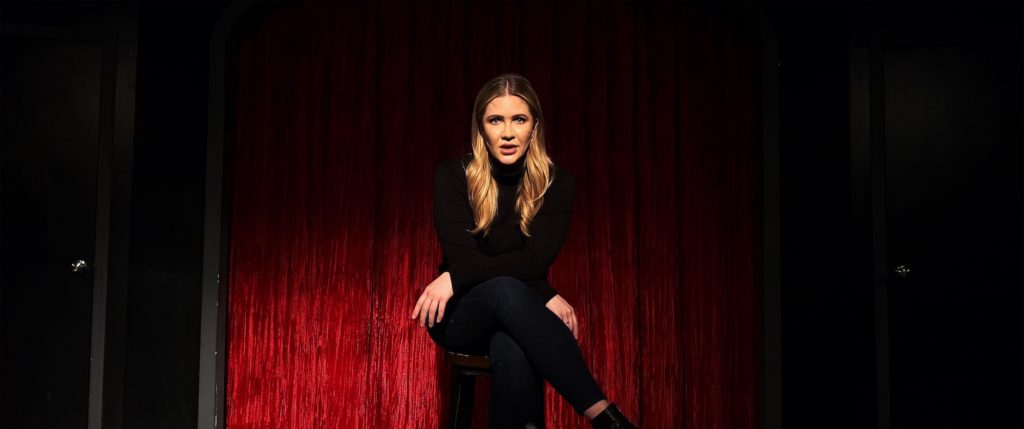

Almost like an anti-stand-up routine, Faye sometimes breaks the plot with small “confessions” given by the protagonist in front of an undefined audience, in which she shares intimate moments of her life, as well as bits of pitch-black comedy. The film briefly touches on horror classics such as Halloween, The Craft and Jaws with insightful jabs (or “roasts”) from the perspective of a trauma survivor. There’s even a fourth wall-breaking moment in which Faye quotes from a review of her newest book, which sounds like it’s actually commenting on the movie itself in a manner similar to the self-aware slasher films which succeeded Scream. The house Faye inhabits is filled with motivational slogans and almost designed to drive away any dark thoughts – just an extra layer of existential hell for Faye, who increasingly gives voice to the idea of just giving up on everything.

For a movie shot on a phone, Faye looks a lot better than most low-budget fare; having gone through a filmmaking process described by Amond as “unorthodox”, it’s a testament to the power and creativity which often drive independent horror. Other stellar movies and TV shows about grief- such as A.T. White’s Starfish, Josephine Decker’s The Sky Is Everywhere or Amazon Prime’s Undone – often visualize dealing with grief in bold ways, while Faye relies almost entirely on simple, but effective techniques, on its powerful writing and superb performance. Often making use of natural light and inspired sound design, the movie’s incursions into supernatural horror are well-timed and downright terrifying, and the viewer feels like they’re stuck with Faye on a carousel to their own worst nightmares. There’s a panic attack episode that will feel oddly familiar to everyone who’s ever experienced one, with the strong editing managing to complement the writing like finely tuned beats.

Faye feels as potent an exploration of mental illness and trauma as Dream Theater’s Six Degrees of Inner Turbulence (a 42 minute-long track with sections touching on bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, and dissociative identity disorder). The camerawork often recalls this year’s brilliant See For Me in making the house seem like a maze that Faye must navigate in her various states of mental unrest. Faye is a movie that “keeps it real” – even Harrison Atkins’s Lace Crater, a movie similar to Faye in some ways, turned to body horror and the confrontation with the absurd in order to depict the aftermath of a woman’s encounter with a ghost. By contrast, Faye only has one scene which could have turned into a spoken-word poetry segment, with an instrumental electronic beat almost punctuating the protagonist’s near-rhymes, but the movie – perhaps wisely – snaps out of it and doesn’t opt to go for that heightened reality, the cherished escape that poetry can often afford. The bated breaths, the disturbing creaks, and the potential of terror lying just around the corner are the kind of tools in the movie’s arsenal–it doesn’t need anything else when it features a performance as strong as Zanotti’s.

Faye ends up exploring a myriad of fears: the fear of loneliness, failure, the difficulties of coping with overnight fame, and even a special fear that is almost like a flipside to faith – the fear of being evil in spite of one’s best behavior. Zanotti’s mind-blowing turn can be compared to that of Aubrey Plaza in Ingrid Goes West or Natasha Lyonne in Antibirth (and that’s no small praise), with Faye even sharing some DNA with Matt Spicer’s film in exploring how social media and image culture can aggravate the downward spiral and exacerbate the negative feelings of their users. The “live breakdown” scene will have viewers almost praying that it doesn’t end up the same way as in Ingrid. (At first, Faye’s Instagram followers seem surprisingly eloquent and even supportive enough. However, when she’s near rock bottom, the commenters turn to trolling, and even what is known in the online world as “griefing” — spamming, or adding random text or profanity to the chat with the sole purpose of sending the recipient over the edge). Zanotti combines comedic timing with a bravura physical performance, playing multiple versions of Faye and making the viewer more afraid of what’s about to happen when her character is actually being calm. When she’s not, the movie simply zooms in and Zanotti is able to provide some of the most iconic reactions in modern horror.

With a finale that plays out like a harrowing encounter in a hall of mirrors, Faye is a stark reminder of the fact that people are more complex than we often make them up to be. Beyond the grief, the protagonist’s confessions reveal that one cannot narrow down traumatic events to a single source, and demonstrates once more that the late Roger Ebert was right to call movies “empathy machines”. Faye is one of the most likable protagonists in recent horror – even if the character repeatedly describes herself as “not nice”. Amond and Zanotti have created an unforgettable one-woman show and only prove that the future of horror is female and that independent horror will continue being vital to the genre.

Faye is now on digital platforms from Reel 2 Reel Films.

More Film Reviews

“The Empty Man is a supernatural horror film based on a popular series of Boom! Studios graphic novels. After a group of teens from a small Midwestern town begin to… Stanleyville (2021) has a simple premise: five contestants compete in a contest to win a brand-new habanero-orange compact SUV. Maria joins hoping for a chance at transcendence, but the other… Heading back to the coastal town where he is haunted by the memories of a past friend, Martin ends up meeting Lucas and the two begin to search for clues… Down and out, and possibly facing a midlife crisis, Georges decides he wants to change things up. The first thing on the agenda comes from a unique purchase, a deerskin… Combining elements of half a dozen genres, The Long Walk is a surprisingly cohesive supernatural time travel drama from Laos, the most recent Southeast Asian country to break onto the… Warning: The soundtrack for this film is very likely to trigger migraines. The first scene immediately sets the tone by framing a death scene with discordant, high pitched metallic sounds…The Empty Man (2020) Team Review – Fear The Abyss

Stanleyville (2021) Film Review: Is the Car Really Worth It?

Phantom Summer (2022) Film Review – The Opera Macabre

Deerskin (2019) Movie Review by Quentin Dupieux – “Killer Style Never Looked so Good”

The Long Walk (2022) Film Review: Time Travel Trouble

The Feast (2021): A Welsh Last Meal to Remember