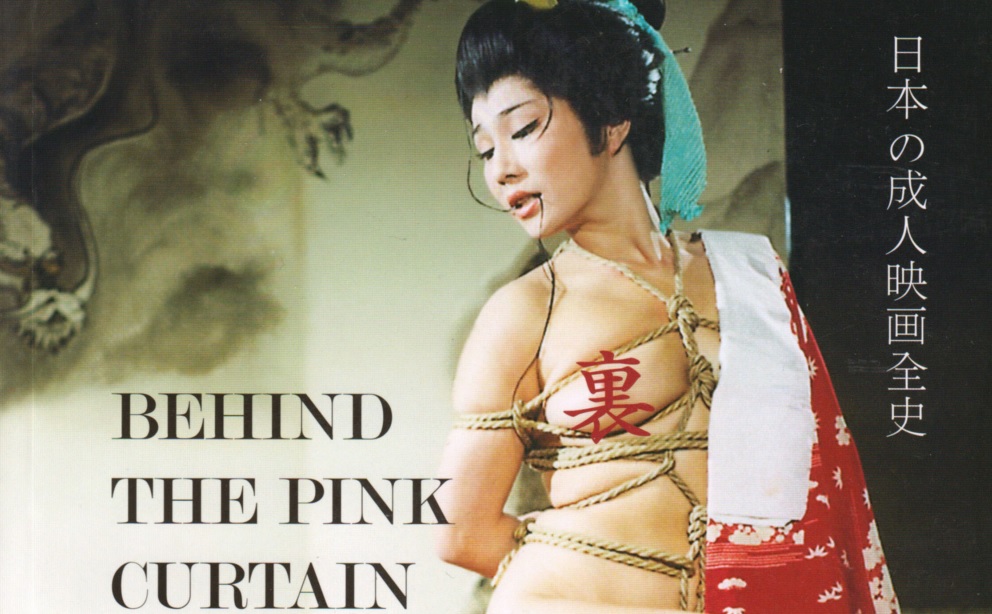

Pinku Eiga, the taboo territory for many enthusiasts of Japanese Cinema. What exactly is it? Are these pictures merely exploitation flicks? Where to begin with the genre? Let’s explore the intricacies of steamy tales straight from Japan together with Jasper Sharp, a film historian and the author of “Behind the Pink Curtain: The Complete History of Japanese Sex Cinema” (2008).

First of all, could you try to briefly define “pinku eiga” for readers completely unfamiliar with this phenomenon?

This could be a bit of a long answer, but essentially these are softcore sex films with stories, characters and proper acting made for specialist adult cinemas. A more strict definition would be independently produced narrative films intended primarily for theatrical presentation with adult content, essentially sexual, and therefore they are rated as seijin eirin (adult films) by Japan’s censorship body Eirin. As their intended market is the cinema screen, for the bulk of its history, from the early 60s to the digital switchover circa 2012, pink films were shot and projected on 35mm film. The cinemas themselves in which they are shown are dedicated specifically to screening these films, and the companies that produce them similarly make films exclusively for this market – although their various productions have circulated vi other means in the home viewing era that began in the 1980s.

What you have effectively is a film industry that sits outside or beneath the mainstream film industry in Japan, or alongside it if you want to look at it another way – but to my mind, they are still narrative feature films.

I should emphasise that what is not encompassed by the term pinku eiga are adult films intended for straight-to-video, DVD, or online, whether hardcore of softcore, nor films produced by major studios with adult content, such as Nikkatsu’s Roman Porno or Toei’s Pinky Violence films of the 1970s. All who work in the pink film industry would definitely stress that this kind of self-contained but independent spirit is what defines the field, although I should add that Nikkatsu did have a close relationship with the pink film (sub)industry during the 70s and 80s. But that’s another story…

In your extremely informative book, “Behind the Pink Curtain: The Complete History of Japanese Sex Cinema” (2008), the first chapter tackles the issue of categorising pink genre. Is it solely art or just an industry? Or perhaps it oscillates between the two domains?

I think this is more a question of how you approach the subject matter, and one can argue either side for any type of cinema. Films are, after all, mainly made to make money. Probably the most instructive way of looking at the field is through what Alexander Zahlten defines as “industrial genres” in his book “The End of Japanese Cinema: Industrial Genres, National Times, and Media Ecologies” (2017), which are non-auteurist works “in which aesthetic generic formations are inseparably bound up with industrial practices”, such as B-movie genre programme pictures, straight-to-video works, etc. Alex was out in Tokyo in the early 2000s researching his PhD thesis on the subject around the same time I was there researching “Behind the Pink Curtain“, so we both mingled together in this field with a couple of other foreign researchers intrigued by a subject, which foreign film critics or scholars hadn’t really paid much attention to before. Pink film is like straight-to-video V-cinema, in that a market exists for a specific product and films are made to satisfy that market in a style largely informed by the way they are consumed.

So in the case of pink films, this is 35mm film where a sex or nude scene is basically required every 10-15 minutes, or on every reel of film, where audiences watch them in the cinema so can’t fast-forward or rewind between the boring bits, so need a narrative to link the films’ raison d’etres and keep them entertained in the interim. The adult cinemas operated triple bill programmes that changed on a weekly basis, so a large number of films needed to be produced by the specialist companies that supplied them just to keep the screens filmed. In this respect, it’s not so different from what companies like Nikkatsu were doing with their yakuza, action and youth movies in the 60s – cranking out films just to satisfy a demand. Another thing is that because of censorship constraints for much of pinku eiga’s history, where you couldn’t show pubic hair or anything particularly explicit, the filmmakers had to find other means to stimulate the imagination.

That’s the industry part of this, and a lot of films were therefore variations on a theme, understandably so given the sheer volume of such titles and the pink industry’s output. The format does allow for some leeway for experimentation however, and it is the ones that deviate from the formula that are perhaps the most interesting to me, in the way that people are more interested now in the films directed by the likes of Seijun Suzuki at Nikkatsu in the 1960s more than those by other directors working for the same studio; those who operate within a tight framework and do something unconventional within it. That’s where the discussions of art lie to my mind.

So for me as an industrial phenomenon in which pink films made up over half of Japan’s cinematic output in its heyday, right up to the early 90s, its interesting because there’s no equivalent really outside of Japan. But if that all sounds a bit dry, there were some really great films created within this market, and all have their own interest in terms of reflecting the times they were made, such as through their music, fashions, thematic concerns and even the real-life locations they were set in.

How did you personally go down the rabbit hole of pink movies. What were your beginnings with the genre?

In 2001, when I started Midnight Eye with Tom Mes, the first English-language website exclusively devoted to Japanese cinema, only a few had ever been shown outside Japan or were then making it onto DVD. This was just between when Pete Tombs’ ground-breaking book “Mondo Macabro” (1997) and its spin-off Channel 4 series, where amongst other things, he managed to get Chusei Sone’s Roman Porno film Virgin Courtesan (1972) onto British TV, among other rich and rare goodies produced in other parts of the world. So there was an awareness among cult film fans that Japanese sex films were a large part of the country’s film output and that they were pretty different compared with the sort of stuff other industries were churning out in the 70s and 80s. It was just that very few people had seen little more than a tiny sample of them. My first encounter was with Koji Wakamatsu’s Violated Angels (1967), one of the more avant-garde and political examples of the genre, which I saw at the Scala around 1990 on a double bill with Shohei Imamura’s The Ballad of Narayama. I didn’t particularly understand nor even particularly warm to this film at the time, but it stuck with me.

I moved to Tokyo in 2002, and what surprised me was that the genre was still alive and well, with a number of quite visible pink cinemas placed in prominent parts of Tokyo, and then I learned that these were new films, still being produced on 35mm, at a time when no other country was making sex films for cinemas, and certainly not in such a volume – I recall at the time there were around 100 of these still being made every year.

At the time, I was there under my own steam studying Japanese cinema history more generally, watching loads of both new and old films. But it was during this period that Masao Adachi, Wakamatsu’s former screenwriter and a pink film director in his own right, had just come back to Japan after a 30-year period in the Middle East, and there was a lot of hubbub about this “forgotten director”, with a number of retrospectives held of his films in Tokyo. I learned about his involvement in the 60s left-wing countercultural and political movement, his work in experimental filmmaking, and his connection with the New Wave giant Nagisa Oshima, and I realised you couldn’t really separate pink film history cleanly from independent or mainstream Japanese film history. I also met around this time, almost by accident, a number of the younger pink film directors and got to talk to them about the subject. So for me it was really about trying to trace a narrative between the swinging sixties and the then current pink film scene – which, as predicted by many of those involved, has all but died out nowadays with the closure of a good many adult cinemas, especially in areas like Shinjuku which began being cleaned up and regenerated after the announcement of the Tokyo Olympics back in 2012 and the switch to digital projection.

I should add that initially my interest in pink film began as a sideline to studying other areas of Japanese film history. In terms of why I wrote the book – clearly there was a large potential readership out there with a general interest in sex films and erotic cinema, but I think it was similar to what David McGillivray wrote in his intro to his book on 70s British softcore, “Doing Rude Things” (1992): this was a subject that had a clear beginning point and, as it was all but dead at the time, an imminent end point, so it was a self-contained topic that made it easy to narrativize and historicise, and I was in a unique position to approach a lot of people working in the field or older veteran directors, to find out their stories, to get a sort of peak behind the scenes, so to speak.

Do you have an all-time favourite pink motion picture?

I reckon it might be Abnormal Family (1984), which is a really canny and sexy satire on Yasujiro Ozu’s films, which is even funnier if you are familiar with the specific films they send up. I knew about the director Masayuki Suo beforehand because his ballroom comedy Shall We Dansu? made a real impact on my when it went on UK general release back in 1997 and became one of my favourite Japanese films of all time (later remade with Richard Gere and Jennifer Lopez!) I guess Abnormal Family highlighted two important things to me – that certain filmmakers began their careers in this particular field and were able to cut their teeth and channel the experiences into successful mainstream careers, and that within the pink film format, you can experiment quite wildly and do some really interesting things if you are a creative director.

The other two titles that made an impact early on were Kan Mukai’s Blue Film Woman (1969) and Masao Adachi’s Gushing Prayer (1971), which I was able to catch on ropey old VHS copies when living in Japan. The former is very psychedelic and colourful, the latter melancholy, poetic and cryptic, but both really captured the time in which they were made. I was overjoyed to have had the opportunity, when I was organising a number of retrospectives of pink films after my book came out, to get new 35mm prints made up of these films from the original negatives to bring them back to life and introduce them to foreign viewers for the first time, because otherwise they’d be just languishing forgotten in a lab or archive somewhere, but it’s the reason why they’ve recently been restored for Blu-ray. In hindsight, maybe I should have gone with High-School Guerrilla (1969) as the representative Adachi film, as its more fun and I know many people have found Gushing Prayer quite challenging viewing!

And finally, I must say that I love the films from the late 80s and early 90s of Hisayasu Sato, which are sadly forgotten today. They have a reputation for being very dark and violent, but there’s a lot of humour in there, a lot of self-reflexivity on such themes as voyeurism, communication technologies, urban alienation and media violence, and they are really experimental in their style. I wish his work was more widely available.

What are your personal recommendations for readers who would like to get their teeth into the genre.

Well, the Third Window releases in the UK are a good place to start in terms of giving a great idea of the wide variety of styles and approaches to the genre, and I should add that when Stephan Holl of the company Rapid Eye Movies, who put the same titles out in Germany, approached me and asked me what good titles he should consider for a digital restoration, all of these were my suggestions.

Koji Wakamatsu vs. Kan Mukai, which one of these rivalling filmmakers is better in your opinion?

The problem with 1960s pink films is that very little survives – most of the films from this era are considered lost, and Mukai was definitely a casualty of this. Wakamatsu kept the prints of virtually all of the films he produced and directed, and took a more active approach in preserving his own legacy. Wakamatsu’s oeuvre in particular is very distinctive and I think very different from the run-of-the-mill pink films of the day, as much as we can say given that so little from period survives, and indeed he himself later claimed they weren’t really pink films, even though they were made originally for this market. So I think Wakamatsu is by far the more interesting filmmaker for a deep dive into the films from this era.

A few years ago, Sion Sono released via Nikkatsu his movie Antiporno (2016) which was meant to serve as a reboot of the Roman Porno series. Do you think that there is still a place for pink films in reality oversaturated with digital adult videos that can be easily accessed online?

I think the problem with Nikkatsu’s Roman Porno reboot project was that they hadn’t really considered who the market was for this kind of material nowadays beyond those nostalgic for the good old days – I thought it sad, for example, that they didn’t use the opportunity to bring in some women directors to make the new films. I think also that they possibly gave directors too much leeway in terms of carrying on this idea of Roman Porno as a haven for directors to experiment within as long as they delivered the goods. Sono’s film is a great case in point. It’s a clever, exhilarating piece of filmmaking, but in terms or eroticism, well, it’s all rather a turn off, I think.

My experiences though from the numerous screenings of pink films I organised after my book came out did seem to highlight there is still a surprisingly large appreciative market for these kind of films, and that there are plenty who want to watch material that is erotic without being graphically explicit. Obviously sensitivities about issues such as gender politics and sexual violence have changed a lot in recent years and vary from country to country, but I think there’s still a lot of potential in exploring eroticism through characters, narratives and dramatic setups without just zooming in for leering closeups. And I still think that the older films have lots of offer modern viewers in this respect too.

What are your upcoming plans at the moment?

I don’t like to talk too much about ongoing projects, because some take years to reach fruition and I don’t want to jinx them. “Behind the Pink Curtain”, for example, was in gestation for a couple of years before I wrote my first word, and took two years to write. The documentary I made on slime moulds with Tim Grabham, The Creeping Garden (2014), took three years from conception to delivery. All I can say is I’ve got a few things I’m working on at the moment, and except in my full-time job as a disc producer at Arrow, none of them are related to Japanese cinema.

Thank you for the interview.

If you are interested in Jasper Sharp’s work, you can follow him on Twitter. If you can’t enough of reading about pink films, then feel free to check out Grimoire of Horror’s film reviews and editorials devoted to this subject matter.

Endnote: The feature image comes from Pink Thrills: Jasper Sharp on Pinku Eiga featurette originally released by Third Window Films (Pink Films Vol. 3 & 4).

More Interviews:

Interview With Horror Artist Mark Gagne of Mindmelt Studios – I’ve Always Been Drawn to Dark Imagery and The Paranormal

The work of artist Mark Gagne strongly resonated with me on first impression, particularly the placing of shadow figures into a decayed landscape through photography. ‘Shadow people’, have become a…

An Interview with Alan Jones – Famed Film Journalist

With the launch of the Jan 20 launch of FRIGHTFEST SATURDAY SCARES WITH ALAN JONES on Fast TV channel NYX, Alan recounts his rise to journalistic prominence – from stealing…

Interview with Alex DiVincenzo and James Cilano of Witter Entertainment [Video Content]

Check out our newest interview with James Cilano and Alex DiVincenzo, the masterminds behind Witter Entertainment and Broke Horror Fan. They have been hard at work releasing beloved classics as…

Michele Michaels Interview – Discussing the Making of The Slumber Party Massacre (1982)

Most notable for playing Trish in cult 80s slasher The Slumber Party Massacre, Michele Michaels is an American actress and writer born in Orange, California. Landing her first acting role…

Oliver Ebisuno is a guy who likes watching (and reviewing) Asian movies. I have my own blog, Watching Asia Film Reviews, and I’m also submitting articles as well as editorials to MyDramaList, Kayo Kyoku Plus, and Asian Film Fans.

![Interview with Alex DiVincenzo and James Cilano of Witter Entertainment [Video Content]](https://www.grimoireofhorror.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Interview-Witter-Entertainment-365x180.jpg)