Monster is the magnum opus of mangaka Naoki Urasawa and a Cold War psychological thriller – it is a seinen manga also adapted into an anime following the whole story exactly. It follows a Japanese neurosurgeon, Dr. Kenzo Tenma, who has residence in Germany to work at Eisler Memorial. Engaged to his boss’ daughter and with optimistic prospects in his medical career, Tenma’s values soon hijack any stable life as a darkly dramatic irony – he was only trying to do the right decision(s) morally: a tragic statement that ‘right’ doesn’t entail the best results. His life is sidetracked into revolutionary conspiracies from the Soviet bloc, violent machinations of a criminal underworld, and a boy, Johan, who’s a nihilistic catalyst of chaos; all these intense affairs are to the backdrop of relatively ordinary existence as a shocking duality showcasing the thin veil between horror and normalcy as is also applicable to our nature. Stylishly European in every day as an atmospheric overture, with the location rife for intrigue as close to the Iron Curtain, Monster is an incisive examination of human nature – the cause of ‘evil’, why and who is truly responsible; the whole work, too, acts as a character study in conscientiously designed personalities who’re palpable as representations to the human condition.

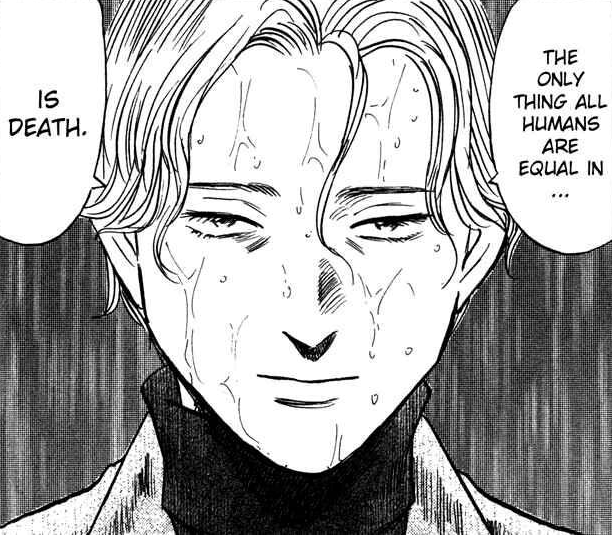

Dr. Kenzo Tenma sacrifices his career to save Johan as a child in a dilemma of choosing a patient for his expertise – the town’s mayor or an innocent boy shot in the head – and although demands to save the mayor for financial reasons, he opts for Johan as he arrived first in the staunch belief ‘all lives are equal’. These philosophical and moral systems are the root of Monster – how these inform and challenge one’s life choices to the darkness we may encounter as aberrant of all we thought as usual; beliefs are easier in a vacuum of a solitary life or with a confirmation bias. Tenma’s choice would have unforeseen, destructive ramifications for which he takes responsibility, too, for which no attitude could prepare him – he had saved a boy who would evolve into a ruthless, charismatic leader of mass destruction. If he knew of the outcome, would he still have performed his duty as a doctor and thought of Johan as ‘equal’ – this is the central concept that tests Tenma’s view on the worth of lives, his right, too, to intervene and act. As he’s demoted for his failure with the mayor, and his lover leaves him as no longer financially secure, the senior staff at the hospital responsible for his punishment all coincidentally die in a poisoning while the boy, Johan, disappears.

The investigation leads to nowhere and Tenma is restored in his role, he subsequently becomes the Chief of Surgery at the hospital nine years later. Destiny would have him reencounter Johan who’s an adult, however, who callously executes a patient as a clear reality the boy he rescued was indeed evil. This refocuses the old investigation onto Dr. Kenzo Tenma who benefited the most – a detective, Inspector Lunge, of a federal agency is convinced Tenma is behind all these crimes, ‘Johan’ a mere persona of his. Escaping from his normal life as the police seek to frame him, and determined to resolve his responsibility of ‘Johan’, Tenma embarks on a tenacious journey as a fugitive.

Supported by a vast cast, who are each developed immaculately, and each embroiled in extensive subplots concerning these, Monster is a ‘coup de maître’ as a psychologically intimate drama with an array of emotions from these characters as an expository fiction of humanity – powerful from the complex dilemmas and philosophical challenges we see engage them throughout the voluminous narrative. Deliberately meticulous in characterization, contemplative in tone and purposeful in each plot point, Monster is a crafted tale sure to resonate with audiences for a long time at a fundamental level – it indulges in themes perpetually inherent to society, no matter the current state. Patience is rewarded in appreciation of the story as an emotive tale crafted into an intricate character study.

The art style is refreshingly realistically rich with a poignant score in the animation that speaks to the musing themes, characters have detailed designs (e.g. motives, gait, expressions, fashion) for expressive nuances, and the atmosphere is comprised of a European sensibility in a gritty ambiance reminiscent of neo-noir and the general plot is respectably mature while also philosophically interesting – this is a manga (along with the anime) to be regarded highly as classical literature (or a show as in the animation that’s practically an exact copy of the manga). The plot structure is a slow-burn of side plots and miscellaneous errands to establish a vibrant world consisting of various personalities, agendas, and their interactions: no man is the same – each one has their own history – and valid perspective along with sympathetic emotions. The characters and situations are also not limited to the overpowering arc of a showdown between Johan and Tenma – people have their own multifaceted lives to not merely be props for the plot. As a result, Naoki Urasawa’s depicted world is tangibly immersive, both in the depth and also sober art, which explores darkness in a manner that’s not crudely exploitative, it is innocently inquisitive: a treatise of our morals in conflict to the worst of humans.

As we uncover brainwashing programs, state violence, ideological radicalism, institutional abuse, and other systemic issues of a seemingly benign society, underneath the shallow interactions of these characters while such a significant influence, we have an interesting overview of the ‘trickle down’ effect in terms of morality – a corrupted society has the byproduct of inducing debased citizens who’re reflective of these vices, corroding the core integrity as a ripple: a national decline. In the backdrop of such moral decay, and those in power being subversive to the common welfare, are these consequential ‘monsters’ truly to blame as are their parents? Monster is aware of such mechanics in the social fabric of society, however, and not only presents a cutting commentary, it provides a purpose to this in an implicative plot: a conspiracy to weaponize human nature against itself as an experiment to initiate internal disorder amongst countries.

“Pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart. The really great men must, I think, have great sadness on earth.” ― Fyodor Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment

Monster accomplishes itself as a darkly philosophical work on society, people, and their beliefs – it is the finest psychological horror, mystery drama, and crime thriller in the history of manga as a comprehensive feat; it is a multi-layered narrative – little contrived or for some cheap ulterior purpose – with equally compelling characters. The setting of Eastern Europe in the throes of the oppressive Iron Curtain is unique an aesthetic that feels authentic – a dangerous regime where the authorities are unreliable and a sense of overbearing danger throughout from leadership which does not truly care for the people. I would rank Monster on level with Fyodor Dostoevsky’s ‘Crime and Punishment’ as a testament to the quality and feel only the medium, manga/anime, besets a prejudice on qualifying Monster to the canals of worthy artistic heritage.

“And slowly, you come to realise

It’s all as it should be

You can only do so much.”

― David Sylvian, For The Love of Love [Monster Anime End Song]

More Anime Reviews:

Alien from the Darkness (Inju alien) is a 1996 adult sci-fi horror anime OVA, written by Shino Taira and directed by Norio Takanami, and distributed by Pink Pineapple. This title… While I’m only four episodes in so far, Wonder Egg Priority is my favorite anime of this season, and perhaps the last several years. Has a worthy successor to Madoka… When it comes to horror subgenres, body horror is, by far, the most impressive visually – the loss of bodily autonomy in the most horrendous and intimate way. As such,… A Kite (or simply Kite to Western audiences) is a 1998 OVA anime, written and directed by Yasuomi Umetsu. Originally released as two separate episodes on VHS, all subsequent DVD… Higurashi When They Cry, or Higurashi no Naku Koro ni in Japanese, is an sprawling franchise of Ryukishi 07 – starting with the amateurish visual novel series in 2002 only… Anime opening and ending songs are often the presentations for whatever show you want to watch for the first time. They try to convey the tone and themes that the…Alien from the Darkness (1996) Anime Review

Wonder Egg Priority (2021) Anime Insight – You Have to Crack a Few Along The Way

11 Best Body Horror Anime Of The 80s & 90s – A Vessel For Visceral Visuals

Kite (1998) Anime Review – Film Noir Action

The Sprawling Franchise of Higurashi When They Cry

Top 10 Deceitful Opening and Ending Songs for Unusually Dark and Disturbing Anime

Some say the countdown begun when the first man spoke, others say it started at the Atomic Age. It’s the Doomsday Clock and we are each a variable to it.

Welcome to Carcosa where Godot lies! Surreality and satire are I.

I put the a(tom)ic into the major bomb. Tom’s the name!