Co-Author Lisa Lebel

The term dissociation, coined by French psychologist Pierre Janet, is defined as an “involuntary escape from reality characterized by a disconnection between thoughts, identity, consciousness and memory.” It is now believed that any person, regardless of race, age, and gender can experience dissociation, but this was not always so. Janet argued that dissociation only occurred in people who had a “constitutional weakness.” Freud’s theory of psychoanalysis included the notion of “defense mechanisms,” while Jung saw dissociation as a normal function of the psyche. It is now agreed upon that the symptoms of a dissociative disorder usually appear because of a traumatic episode. Symptoms of the disorder usually include out of body experiences, memory loss, emotional detachment, a lack of sense of self-identity, and severe depression. Dissociative Identify Disorder (DID, or multiple personality disorder) is an extremely controversial example of a dissociative disorder, and the past treatments for it even more so.

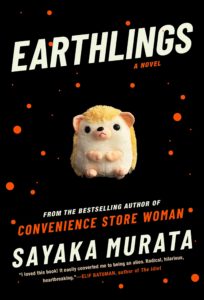

Japanese author Sayaka Murata’s book Earthlings, released in 2020 (trans. Ginny Tapley Takemori), seems to focus on the effects of dissociation (namely depersonalization disorder) on three characters who, since early childhood to adulthood, refuse to conform to societal norms. This isn’t because they don’t want to, but because they seem to be “wired that way” – or it might actually be about aliens with the power of indoctrinating humans to a new way of life, trying to live among them. (It’s worth mentioning that The Grimoire’s own Javiera Vega reviewed the book, stating that it while it seemed to focus on Chūnibyō, a Japanese term describing elementary school students who develop delusions of grandeur, it develops into something much darker).

Earthlings starts out with a family trip to the region of Akishina in order to celebrate Obon (a holiday focused on ancestors) and sees young protagonist Natsuki eager to meet her distant relatives – especially cousin Yuu. Natsuki believes that she is an alien from the planet Popinpobopia, and that she can speak to her plush hedgehog – actually a magical power-granting entity named Piyyut. When Yuu, whose mother depends on him “as though he were her husband,” confesses that he is an alien too, Natsuki surmises that they must be from the same planet. Together, they start looking for a spaceship. The two had already shared a close relationship, but they end up exchanging marriage vows in order to cope with being separated, only able to see each other every year during Obon. Their marriage pledge states:

1. Don’t hold hands with anyone else

2. Wear your marriage ring when you go to sleep

3. Survive, whatever it takes

Why would two young, sweet, innocent-looking kids add survival as a clause in their marriage contract? While Yuu’s reasons for thinking himself an alien are more complex, Natsuki’s are soon made evident when she returns to her urban existence. Natsuki’s friend Shizuka has a crush on their teacher, Mr. Igasaki, and it turns out that Igasaki is less interested in education and more in the “private lessons” he wishes to impart on Natsuki. Igasaki tries to disguise his sexual abuse with reassuring words and appeals to authority. On top of being abused by her teacher, Natsuki doesn’t have the best relationship to her family either, and she sees society as a breeding farm, referring to it as “The Factory.” In her view, people’s reproductive organs don’t belong to them, but to society, and disobedience automatically places one under the merciless gaze of “The Factory.” The only real aim is procreation, and a strict culture of control is a means to this end.

Art by Kai Ussin – “Planet Two”

“I like to look at humans from a distance, I enjoy watching nature programmes – they’re always about reproduction, so maybe my novels are nature programmes about people.” – Sayaka Murata on “Earthlings”

Earthlings might have been born out of the pressure felt by Japanese women in the wake of Hakuo Hanagisawa’s 2007 public statement that women should perform a public service by helping to raise the country’s birth rate. Whenever she senses that sort of pressure, or is a victim of abuse, Natsuki ends up partially unable to use a body part, such as her mouth or one of her ears. She develops the ability to free her spirit from her body and watch herself during traumatic episodes. Derealization, survival, individuality, the rejection of traditional norms, alienation and parasitic relationships are major themes in Earthlings, and the phenomenological term of “the Other” is explored every step of the way. Natsuki, Yuu, and later, Natsuki’s husband Tomoya (who is even more radicalized than Natsuki, possibly because of his abusive parents) – in short, people who have been “othered” – are still expected to function normally and produce offspring. As a retort, they attempt to subvert societal expectations through developing and nurturing a fresh gaze (referred to as “the alien eye”).

Alienation has been a long-standing theme in Japanese literature, together with dehumanization. Yukio Mishima’s “The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea” examines the rejection of Western values. Kobo Abe’s “Box Man” sees a man living inside a large carton in an attempt to become no one, or anyone. Hitomi Kanehara’s “Snakes and Earrings” and Ryu Murakami’s “Almost Transparent Blue” use a discourse of disappointment in order to depict worlds filled with violence. If one looks even further back, there are Osamu Dazai, Kenzaburo Oe, Junichiro Tanizaki, Yasunari Kawabata – all examining feelings of alienation as gateways into suicidal ideations, erotic obscenities or injustice. In telling stories about alienation, both Kawabata – in his seminal “One Arm” – and modern writers like Haruki Murakami, Banana Yoshimoto or Hiromi Kawakami have turned to magical realism.

Angel Flores defined magical realism, a term originating in Latin-American literature, as “the amalgamation of realism and fantasy.” Lindsay Moore, in her 1998 essay“Magical Realism,” describes the term as a “literary mode” rather than a genre in itself, creating multiple realities in an attempt to examine “the union of opposites.” Magical realism thus differs from pure fantasy in its real-world settings and normal protagonists, but the lines between it and surrealism (or, more recently, just supernatural horror) are sometimes blurred, chiefly because the literature comes with at least two different modes of interpretation built in. This is why Moore lists important themes which are linked to magical realism: terror, authority and its ability to torture or kill, time and revolution. In her view, the characteristics of magical realist literature are the opposition of urban and rural spaces, a writer’s ironic distance and respect of the magic present in the novel, and their lack of clear opinions on the matters presented.

Going by Moore’s definitions, “Earthlings” is indeed a work of magical realism. There is the normal world and the planet Popinpobopia, possibly tucked away in some secret corner of the universe. There is trauma in the hearts and minds of each character, the terror resulted from the mental separation from the societal body, and later on, from having to resort to extremes in order to survive. There is a sizeable time-skip, the three protagonists could be viewed as revolutionary figures, and the novel shifts its setting from rural to urban, modern to traditional, busy and desolate. However, there is a fine line between the respect for magic and the ironic distance used by a writer, and Murata opts for the focusing on the latter: her sentences are short, and the prose detached, emotionally flat – almost an act of dissociation in itself – but she sneaks in some deadpan humor from time to time. Examples of her deadpan snark would be the three characters each performing a “divorce ceremony” (stating that they will “live as a completely separate entity, for better or for worse, for richer or for poorer, and in sickness and in health, and (…) shall not love, cherish, or worship”), coming up with the missing ingredient for their meal consisting of Miso Soup, Daikon Leaf, Stir-Fry, and Sweetened Soy Sauce, or Tomoya trying to persuade his brother to have sex with him in order to get back at society. Ginny Tapley Takemori perfectly transposes Murata’s unique voice in English and the elegant prose is a large part of the reason for why the book is a hard one to put down.

Art by Kai Ussin – “Planet Three”

“I don’t think women writers are content to be confined to any particular subject or style, and in some cases, they explode these boundaries in quite spectacular and innovative ways, like Sayaka Murata with Earthlings.” – Ginny Tapley Takemori in an interview for Asymptote Journal

While one could also place Earthlings in the category of dystopian fiction, the term “dystopian” usually coins a work depicting a society in which the promise of a perfect existence has gone horribly wrong. Meanwhile, magical realism focuses on our current society – juxtaposing the good with the bad, offering magic as a release. In addition, a dystopia is almost always about the violation of basic human rights or some freedom, but while Earthlings does focus on the aftermath of society’s unspoken rules on the lives of three ill-adjusted characters, the violations of their freedom to not produce any offspring is mostly perceived. The strict regulations (also perceived) are a result of broken familial bonds, not a well-established society seeking to punish the rebels. Earthlings is more about family units and parents, siblings or close friends pressuring children, crushing their dreams. It’s less about society enforcing its rules through neon billboards – although workplace injustice is briefly touched upon.

While it’s never outright stated whether Popinpobopia is real or not, Murata’s adherence to the horror genre and the ease with which a reader with some knowledge of psychology can see Natsuki’s entire state of mind as a result of depersonalization disorder end up diluting the novel’s magical realist approach. Murata’s aim might be to depict alternatives against traditional norms, but the result is a horror book through and through, as the mildly antisocial beliefs of these characters turn into a struggle for deculturalization and survival that borders on the grotesque. In that respect, it’s closer to Ryu Murakami’s “In The Miso Soup” (the mundane interrupted by disturbing, grotesque acts), Eric LaRocca’s recent novella, “Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke” (through shared motifs like contracts, trauma, child abuse and things that are not meant for human consumption, the Internet as a means of resistance, and possibly the entire ending), and Sion Sono’s “Cold Fish” (a harrowing “disposing of the body” scene).

Earthlings is a witty takedown of modern society’s obsession with legacy and furthering the species, but it is also a long list of taboos, each carefully weighed in and viewed from a telescopic distance, as if the readers were indeed forced to inspect a distant planet: the first chapters depict incest, desecration of grave sites, pedophilia, and (hilariously enough) child marriage. The truly disturbing ones occur in the last chapters, but Murata’s careful prose and adoption of first-person perspective always make the reader “part of the gang,” as if they too have been indoctrinated by the alien eye of Popinpobopia. Earthlings does not start off with a long list of possible trigger warnings, partly because it wouldn’t fit in with the aesthetic facets of magical realism and alien sci-fi (some readers will be sad to learn that Murata doesn’t opt to explore, or deconstruct the “magical girl” aesthetic in the way Puella Magi Madoka Magica did), partly because nothing horrific is stated outright – it merely happens, and later on the novel considers the consequences. When faced with reality, the protagonists are too ill-equipped to discern it from their way of thinking – let alone handle it. Passing off horrific events as happenstance in one person’s point of view is difficult to accomplish, and Murata’s use of this literary device is masterful.

The irony consists of the group behaving as a unit, but insisting on individuality. The dynamic between the three could even be seen as the classic “Freudian trio”: Natsuki is the ego, Tomoya the id (definitely the more psychotic of the three), and Yuu the superego. In their quest to resist the urge to procreate, they comically strut around naked and live with the lights turned off. They steal food from the surrounding houses and protect themselves from home invaders. When faced with the possibility of extinction, they debate who is worthiest to live on. Belonging in the group seems to heal Natsuki, but it does more harm than good to Tomoya and Yuu. Murata explores the fascinating failures resulted from three people who reject civility but who are still bound to language and communication, failing to find a different common grammar – although, at times, they come pretty close. Each time the group commits a transgressive act, they do so outside the boundaries defined by society, but society would never struggle in finding a label for them – that of criminals, or even terrorists. Each time, they debate their actions, opening themselves up to the limits of language and their own differences. They use human logic and reasoning tools, like prioritizing and making short-term sacrifices in order to achieve long-term gains.

The ending, depending on how one chooses to interpret it, might seem like a mind-melting dream-state (psychedelic drugs are also able to cause dissociation, after all), a cautionary tale ending, or just a shocking one, depicting the last stage in the development of alien beings. Each chapter can be seen as a moulting process, and the silkworm, which moults 3-4 times during its growth, is a recurring motif. What Murata really excels at with Earthlings is running an interesting social experiment akin to Anna Odell’s “X&Y,” a meta-analysis of sorts, one with clear don’ts, but unclear definitions and roles to be played. It is never clear if the experiment is one closer to a book like “I Never Promised You A Rose Garden“, Joanne Greenberg’s semi-autobiographical work about a girl suffering from extreme delusions describing a fantasy world to her doctors, or “One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest” with the entire society in the role of Nurse Ratched, or the Czech surrealist film “Daisies“, which sees two women playing pranks in order to get back at authority, traditional morality and social norms. Going by these last examples, perhaps the protagonists of Earthlings would have been better off by using a stealthier, more subversive approach, a more “innocent” rebellion.

Sayaka Murata, author of Earthlings

Earthlings manages to be compelling to both newcomers to Japanese literature and jaded readers. Likewise, it somehow situates itself right at the intersection of psychological horror, magical realism, dark humor and grotesquery, managing to find a unique voice. Murata doesn’t really walk the line between all these concepts, she zips the line – one is never quite sure which mode, which tone the book will adopt when turning the page. Readers are only being increasingly aware of the possibility of a happy ending becoming more and more diminished as the time passes. Society might be easy to hide from, but human nature is the hardest thing to overcome. The protagonists of Earthlings end up shedding their human skin and renouncing their reproductive organs (and sometimes even their eyes) but struggle endlessly to transform themselves when all they find is more and more remnants of their humanity: mouths, arms, feet, flesh, and bone.

More Book Reviews

For the long-awaited conclusion to the Gwendy trilogy, Stephen King and Richard Chizmar reach the final frontier of “don’t push that button!!” horror to bring us the last installment of The… Yami-hara – an abbreviation of yami harassment. Yami harassment is a compound of yami (darkness) and harassment; unwelcome conduct toward a person stemming from darkness in one’s own mind or… Hello, GoH peeps! Dustin here with another edition of Recent Reads coming your way. I’ve got a bit of variety here for you with these three books that I’ve covered. Rest assured,… Gwendy’s Button Box is a collaborative novella by Stephen King and Richard Chizmar. It takes place in Castle Rock, Maine, a place very near and dear to our hearts. We… Demonic possession has always fascinated and terrified many. The idea of losing oneself both physically and mentally to an intangible force feels akin to a dreadful disease. However, as depicted… What is up, GoH friends! Dustin here again with a new batch of Recent Reads. Both of the books in this edition were a change of pace, to say the least. No One…Gwendy’s Final Task Book Review

Yami-hara (2023) Book Review – A Haunting Tale of Darkness

Recent Reads: Unbortion, Why Are You Biting Me?, and Golf Curse

Gwendy’s Button Box Book Review – Stephen King and Richard Chizmar Collaborate On a Castle Rock Novella

Sister of Darkness: Chronicles of a Modern Exorcist (2023) Book Review

Recent Reads: No One Rides for Free, The Whistler